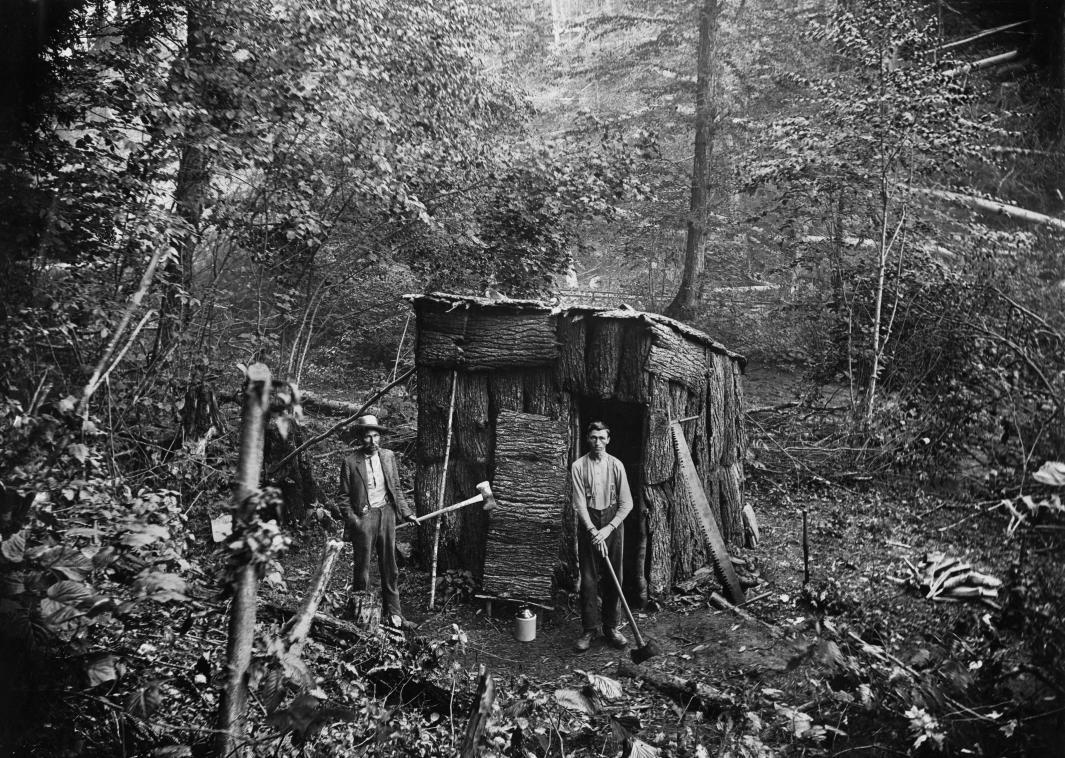

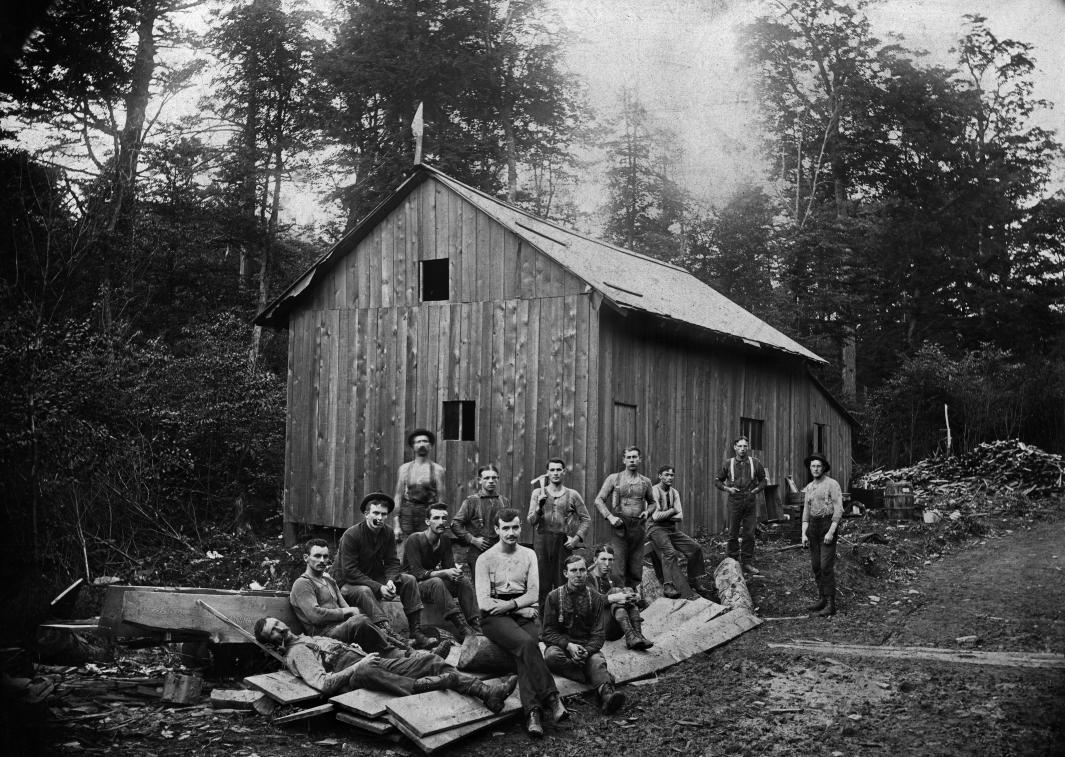

This series of gorgeous, detail-packed photographs, by itinerant photographer William T. Clarke, records the faces and landscapes of the lumber industry in north-central Pennsylvania during the late 19th century. In the span of a few brief decades, lumber companies rapidly processed large areas of old-growth forest, employing men—and some families—who lived in the backwoods in thriving, temporary camps and towns. A book out this month, Wood Hicks and Bark Peelers: A Visual History of Pennsylvania’s Railroad Lumbering Communities, collects 131 of Clarke’s images.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Clarke, the son of Irish immigrants, appears to have carved out a living as a freelance photographer willing to undertake rough travel through the state’s north-central lumbering region. “Much of his income likely came from contracting with lumber companies,” Linda A. Ries writes in the book’s introduction. Clarke made images that might illustrate promotional campaigns or company literature, explaining how timber was harvested and processed. He appears to have supplemented this income with individual commissions from local residents; some of the glass plates reproduced in this book depict family homesteads in the woods or children posed in outdoor settings.

In the early 20th century, reformers interested in protecting Pennylvania forests used Clarke’s images of the thick old forest and the stripped-down hillsides of the present day to argue that lumber companies needed to be held accountable for the destruction of the forests in the state. We know little about Clarke’s personal feelings on the matter, but in a 1912 letter to one such reformer, folklorist and journalist Henry Wharton Shoemaker, Clarke wrote:

As you mention the last of the hill forest are about gone And this is the last of it (Around this vicinity) Even at that what a hurry for the fastest mill ever run in this country in now eating up the rees at a rate of 275,000 to 300,000 per 24 hours Why? When the Hemlock can not last there more than 7 or 8 years at most [punctuation in the original]

Clarke stored many of the glass plate negatives he made during his career in a barn, where a large number of them were destroyed when the roof sprang a leak. The images in Wood Hicks and Bark Peelers, which Clarke stored separately, were saved by descendants Lois and Bob Barden. In 1974, the Bardens discovered a crate of glass plates in a toolshed owned by a recently deceased family member. Recognizing their value, but not knowing their provenance, the Bardens held onto the plates for years, before working with the book’s co-author, photographer Harry Littell, to salvage the images and identify their locations when possible.

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press

Penn State University Press