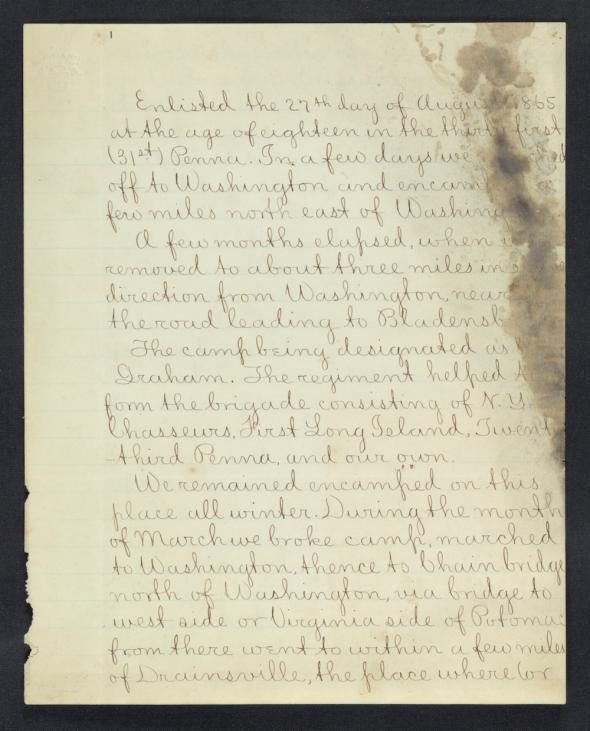

This eight-page handwritten letter by Private Franklin H. Durrah describes his service as a private in the Union Army during the Civil War, which ended with the loss of his right arm. The letter’s neat cursive—and the story it tells—is part of a collection of entries into left-handed penmanship contests for disabled veterans, recently digitized by the Library of Congress. The William Oland Bourne Papers holds nearly 300 letters, photographs, and various recollections, offering an unprecedented look at the stories of heavily wounded soldiers.

Bourne, a chaplain at New York’s Central Park Hospital, used his newspaper The Soldier’s Friend to conduct a penmanship contest for veterans who had lost their right (writing) arm in the Civil War. Bourne offered prize money for the best writing ($1,000 total for the 1866 competition); he hoped that showcasing the winner’s penmanship despite their disability would lead to their future employment. “Penmanship,” The Soldier’s Friend wrote, “is a necessary requisite to any man who wants a situation under the government, or in almost any business establishment.” To enter, contestants were asked to write a letter using their left hand that detailed their service and injury, and, if possible, include a photograph. All told, the collection holds entries for two years of Bourne’s contests, which provide a rare soldier’s-eye-view of combat and recovery.

In his letter, Durrah, who enlisted at the age of 18 in 1861, paints a particularly grim picture of Army life. Picturesque anecdotes such as finding—and hunting—a stray pig in the Virginia wilderness or encountering abandoned Confederate barricades are outweighed by unsettling experiences, such as the Army setting fire to a “woods” during a night retreat or finding a “negro pen” by a Virginia court house. While Durrah remembers having been eager for action, he complains that many aspects of Army life were “not agreeable.” Long marches in poor weather and bivouacs in muddy fields were sometimes interrupted by intense combat before resuming again, with little rest in between.

Durrah recounts that the troops suddenly heard musket fire on a late May morning in 1862 and then got into battle formation in what became known as the Battle of Seven Pines. Eight hours later, a musket ball entered Durrah’s right arm at the elbow and traveled straight through the bone to the shoulder, where it exited. Afterwards, he plainly states, he “walked about a mile to the rear of the battlefield, and there my arm was amputated.”

Some contestants adjusted to society well. Sgt. Seth Sutherland (the contest’s first entrant) was elected to two terms as a county auditor in Ohio, where he seems to have earned a great deal of respect, despite what he refers to as almost constant inquiries about his missing arm. Durrah was not so lucky. Although $200 richer from the contest, he was declared insane and eventually committed to an asylum, for an affliction that most likely was what we would now call post-traumatic stress discorder.