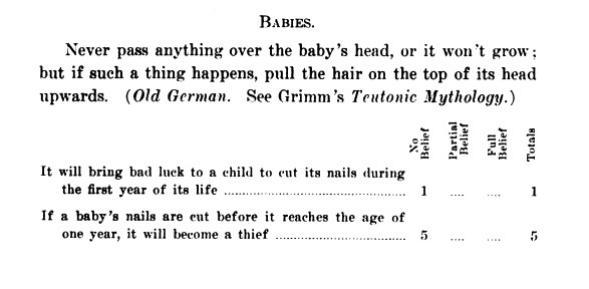

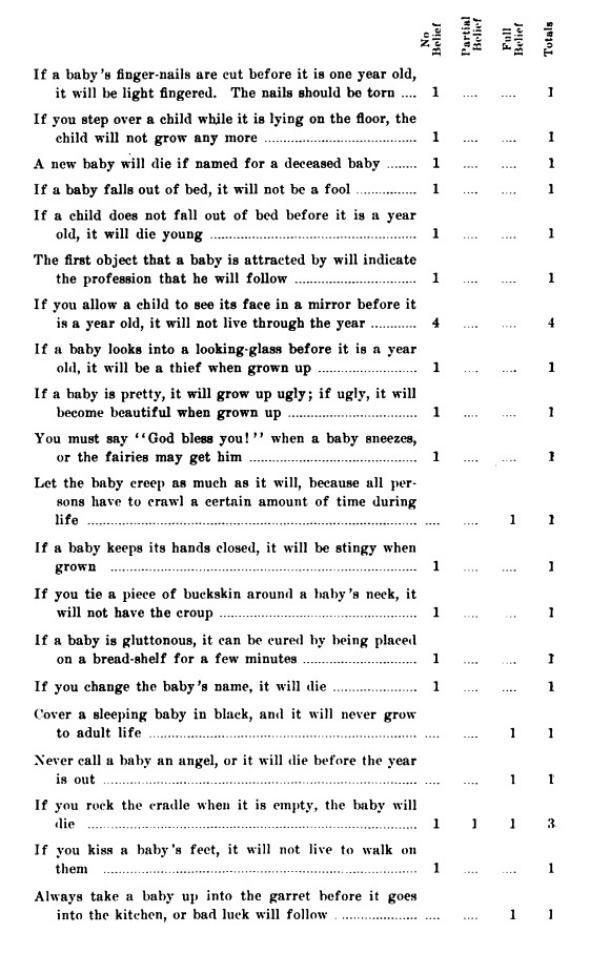

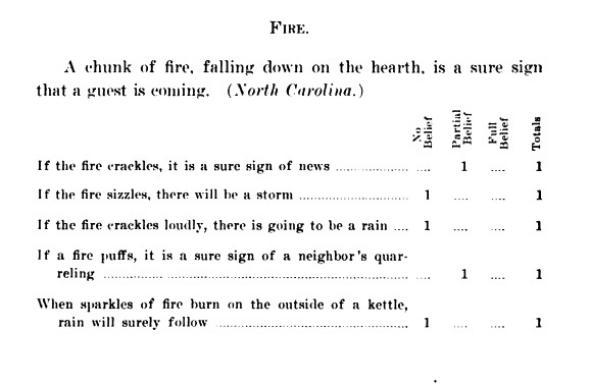

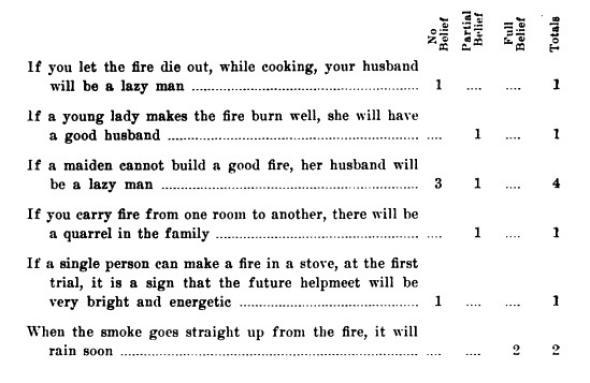

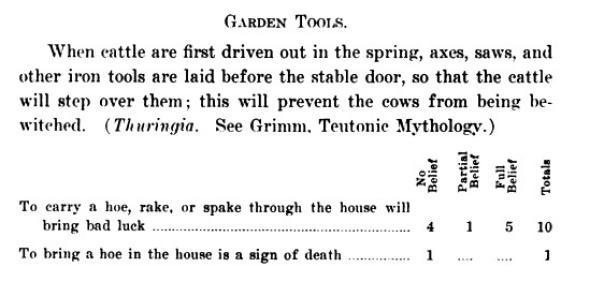

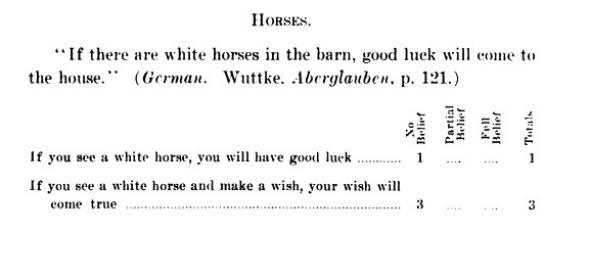

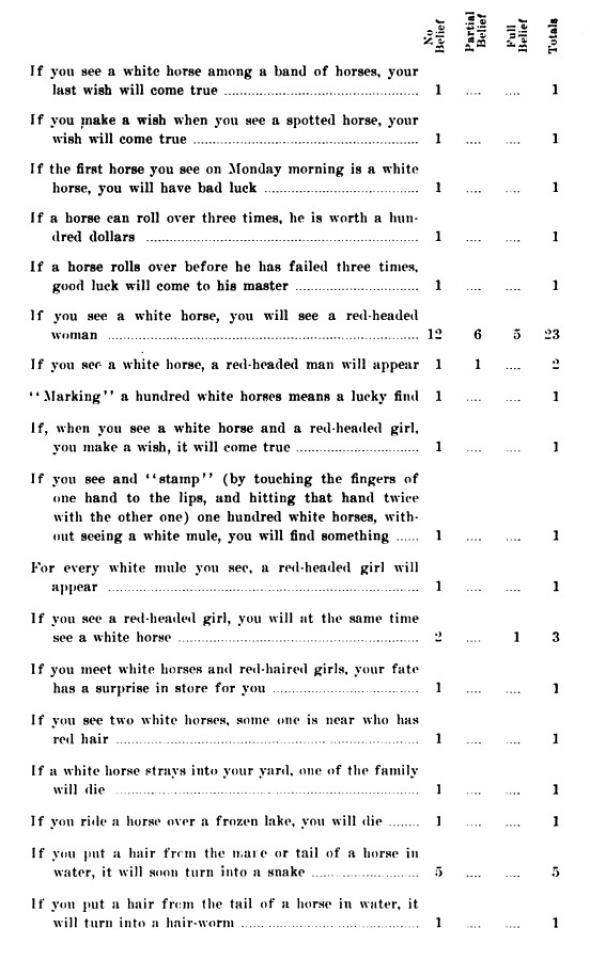

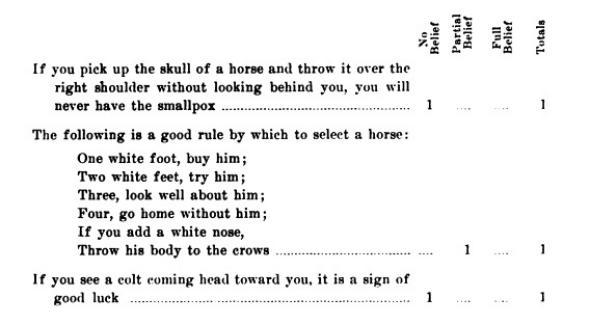

These deeply entertaining lists of superstitions, gathered by Fletcher Bascom Dressler in 1907, are a good sample of the kinds of sayings American college students from across the country heard in their homes in the late-19th and early-20thcenturies. I’ve excerpted a few choice topic areas below, but you can read the whole book, held at Harvard University, in the HathiTrust Digital Library.

Dressler reported that he asked 875 students, mostly women who were enrolled at Berkeley’s school of education preparing to become teachers, to “write out carefully all of the superstitions they knew, each relying entirely on her own memory. No suggestive communication with each other or with the teacher was allowed.” The material was submitted anonymously.

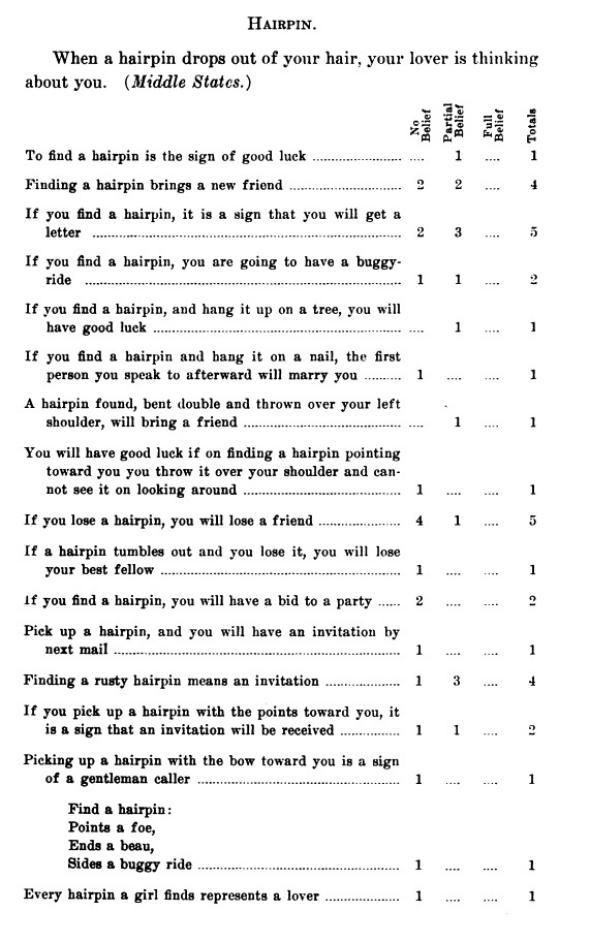

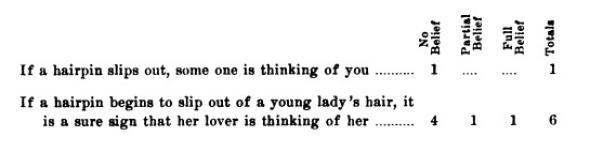

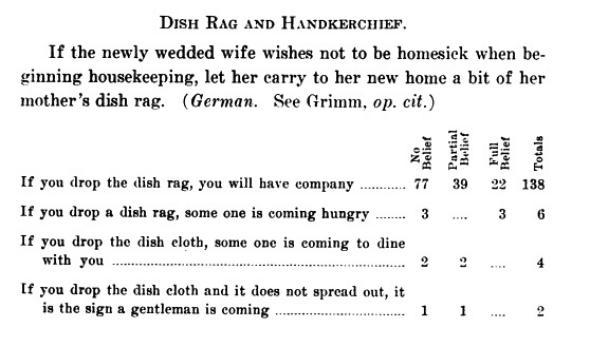

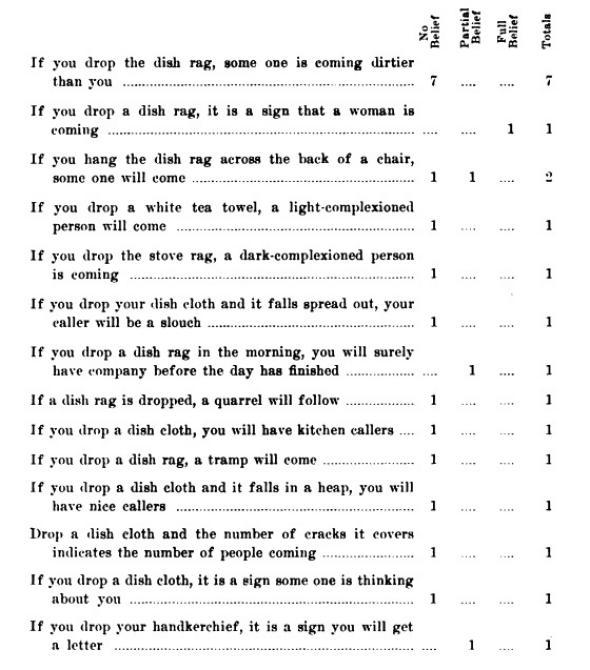

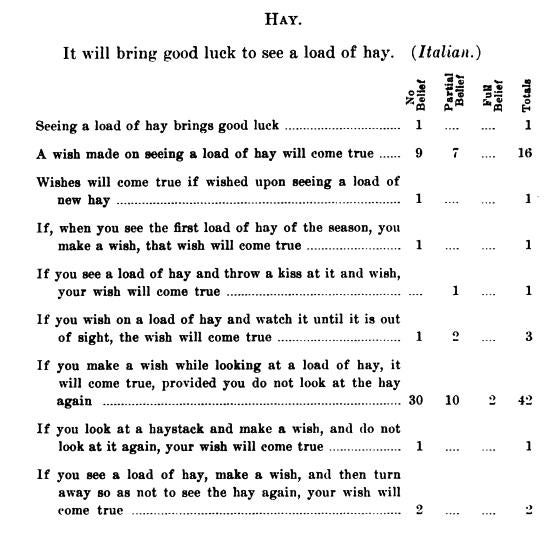

Next to their description of each superstition, students were asked to describe their level of belief in it: “No belief;” “Partial belief”; or “Full belief.” Dressler thought that “partial belief” was as good as belief: “It is an indefinite and conditional belief to be sure, but it may be as persistent and as thoroughly superstitious as ‘full belief.’ ” He tallied up levels of credence attached to each superstition in his report below. Many reported superstitions had no believers at all, but some (like “If you make a wish while looking at a load of hay, it will come true, provided you do not look at the hay again”) had a good number of adherents.

Defending his sample against naysayers who would point out that female students were bound to be more superstitious than men, Dressler wrote

I believe … that men, under favorable conditions, are less ready to believe in superstitions than are women … But history makes it very plain to us, that when men become excited and wrought up in their emotional natures, they are guided far more by emotional and superstitious reactions than by reason. We need only look about us today to see on every hand evidences of their belief in luck, in fortune telling, in clairvoyance, and superstitious influences of various sorts, even during the hours of sober life.

The topic areas of these superstitions, ranging from animals to plants to dish-rags to babies to foods to furniture, form a neat capsule history of late-19th-century American household life.

I first saw this book while browsing the Digital Public Library of America’s Primary Source Sets project.

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust

HathiTrust