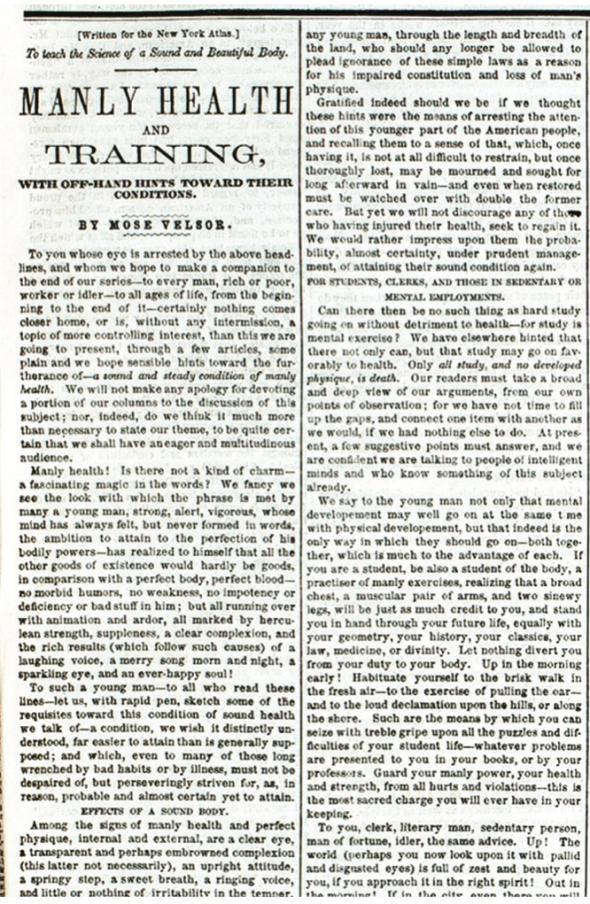

On Friday, the journal Walt Whitman Quarterly Review published a special issue reprinting a series of journalistic treatises by Whitman, expounding on the nature of health. “Manly Health and Training,” written under the pseudonym “Mose Velsor” and published in installments in the New York Atlas in 1858, is 47,000 words long, and you can read the whole thing here.

The internet has received this new Whitman as a quirky document full of prescriptions that seem curiously modern—a proto–paleo diet; walking over sitting; no late dinners—and proto-eugenic attitudes that feel very 19th century. But the document is hard to read, in its entirety. That’s because “Velsor’s” style was garrulous—every idea seems to require more words than is strictly necessary for their expression—but also because “Manly Health” mixes modes so promiscuously.

“One might call it lots of things: an essay on male beauty, a chauvinistic screed, a sports memoir, a eugenics manifesto, a description of New York daily life, an anecdotal history of longevity, or a pseudoscientific tract,” writes Zachary Turpin, the scholar who rediscovered the “Manly Health” series and confirmed its authorship, in an introductory essay in the WWQR.

Here, I’m excerpting the parts of the treatise that sang to me: Whitmanic commentary on the nature of American life, as it was then lived in mid–19th-century American bodies. For me, these sections most clearly illuminate the connections between “Manly Health and Training” and the flooding-forth poetry of Leaves of Grass, first published three years earlier.

I’m including the journal’s page numbers, for your reference. All emphasis in bold is my own, and is meant to point out the parts that—to me! dear reader, to me—most vibrate with Whitmanic energy.

On the misery of the man who fails to train his body (p. 226):

He goes forth, neither feeling nor looking well; he has lived badly—his blood is bad—his joints move like those of some rusty machine, ill oiled—his eyes have red bloodshots in them—his complexion is muddied and pimpled—he is not clean, not having bathed for a long time—his stomach has been overloaded with all sorts of indigestible solids and injurious liquids. This has been going on so long that his digestion is seriously impaired—his bowels are clogged with accumulations of fearful impurity, like sewers that have been stopped—his gait is halting, and he would sit down often to rest—his appetite is morbid, seeking stimulants and spices to excess—the expression that beams from his face is anything but attractive—his breath is bad—nobody finds it a pleasure to be near him, or feels anything like delight from the magnetism of his voice, for there is no magnetism about it—he does not attract women, nor men either; and thus, going up and down, through the city, it may be, in the street, at table, wherever he moves, he is without vigor, without attraction, without pleasure, without force, without love, without independence, spirit or pride. Can there be a much sadder case? And is it by any means a rare one?

On Americans’ bad eating habits (p. 201):

We [Whitman used the royal “we” while writing “Manly Health”] cannot resist the impulse to condemn here, what we consider the frightfully injurious dinners and dinner habits of most people who, as they would call it, “live well.” Look over the bill of fare of any hotel or restaurant, or even the dinner-table of an ordinary boarding-house—see the incongruous dishes that, on the bills, stand in long lists, and that men devour, often three or four different kinds—soups, pastry, fat, fish, flesh, gravy, pickles, pie, pudding, coffee, water, ale, brandy—and heaven knows what else! Not one out of fifty eats a really wholesome, manly substantial dinner. All, more or less, distend the stomach, and bloat themselves with quantities of trash, to worry the digestion, thin the blood, and return, sooner or later, in lassitude, headache, constipation, or a fever, or some other attack of illness.

On young men’s sexual overexertions (p. 277):

This virile power, so becoming to a man, and without which, indeed, he is not a man, seems, in modern life, to be under the curse of an insane appetite, especially among the youth of cities, which makes them think they are doing great things if they commence early with women, and keep up afterwards a huge number of intrigues and amours—having no choice about it, but sweeping at all that is female, as a fisherman sweeps fish into his net.

On the mental misery of most Americans—a dark vision, perhaps inspired by Whitman’s own apparent depressive episode that year (p. 272):

In public, no doubt you would judge from the show upon the surface that every one was happy, and that there was no such thing as a cloud upon the sky of the mind; all goes so well, and there is so much drinking and eating, and joking and laughing and gay music. The faces are full of color, the eyes sparkle, the voices have a ring—everybody is well dressed, and there is surely no unhappiness in these lives. A serious mistake! Many and many a silent hour, both by day and night, does every one here undergo, in which the distress of the mind equals any distress of the body, in its worst sickness or hurt. The evil we speak of, like most other human evils, is not of a kind that flaunts out and exposes itself, but is only to be detected by the powers of insight and acute observation. To those powers there is perhaps no rank of the community, and no group of men collected together, but the presence of it can be plainly seen, passive enough, but still lurking there. It shows itself in the lines of the face, cut and seamed by harrassing [sic] thoughts, and many an hour of discontent and nausea of life.

On a perceived overintellectualization in American life (p. 297):

And yet, as before intimated, a diseased brain, and a sadly inflamed state of the nervous system, are by no means confined to literary men. We Americans altogether, all classes, think too much, and too morbidly, —brood, meditate, become sickly with our own pallid fancies, allowing them to swarm upon us by night and by day.

On the benefits of training (p. 196):

Look at the brawny muscles attached to the arms of that young man, who, for nearly two years past, has devoted on an average two hours out of the twenty-four to rowing in a boat, swinging the dumb-bells, or exercising with the Indian club. Look at the spread of his manly chest, on which also are flakes of muscle which rival those of the ox or horse.—(Start not, delicate reader! the comparison is one to be envied.)

On pugilists—a passage that reveals Whitman in his fly-on-the-wall observational mode (p. 263-4):

We have sometimes even thought, while standing among a large crowd of these sporting men, in some Broadway drinking saloon, or some such place, and quietly observing their actions and looks, that they presented about the best collection of specimens of hardy and developed physique we had anywhere seen. Their movements remind one of a fine animal. They have that clear, audacious, self-confident expression of the eye, and of the face generally, which marks some of the animals in a wild state. Notice the attitudes of them as they stand, or lean; the extended arm holding the glass of liquor, and raising it to the lips; the hat tipped down in front over the eyebrow; the “gallus” style generally. Or, see two of them square off at each other in a joking way; the limber vibration of the upper part of the body upon the waist; one foot planted forward; the movements of the arms, and the poise of the neck.

On the way health begets charisma (p. 224):

Would you succeed in anything?—ambitious projects, business, love? Then cultivate this personal force, by persistent regard to the laws of health and vigor. And remember that the best successes of life are the general resultant of all the human attributes, expressed through a fine physique. This knowledge, this practice, you, too, reader, will need. All kinds of men, herculean, obstinate, petty, profound—men of oak and men of wax—meet you at every move, crowding and jostling through the by-ways of the world. These you would confront, you would command, would you not? At least, you would not be overborne by the proudest of them, but would hold your own on equal terms. Then observe our suggestions—train—acquire for yourself firm fibres, a stomach clear and capable, the brain-action unabused, the stream of vital power full and voluminous, a bright eye, a strong voice, a proper degree of flesh, a transparent complexion—a fine average yet plus condition; and sympathy, attraction, and a heroic presence will follow.

And finally, this passage, extolling the benefits of proper health, also functions as an exultantly joyful paean to life—a cousin to “I celebrate myself, and sing myself” (p. 216-217):

To spring up in the morning with light feelings, and the disposition to raise the voice in some cheerful song—to feel a pleasure in going forth into the open air, and in breathing it—to sit down to your food with a keen relish for it—to pass forth, in business or occupation, among men, without distrusting them, but with a friendly feeling toward all, and finding the same feeling returned to you—to be buoyant in all your limbs and movements by the curious result of perfect digestion, (a feeling as if you could almost fly, you are so light,)—to have perfect command of your arms, legs, &c., able to strike out, if occasion demand, or to walk long distances, or to endure great labor without exhaustion—to have year after year pass on and on, and still the same calm and equable state of all the organs, and of the temper and mentality—no wrenching pains of the nerves or joints—no pangs, returning again and again, through the sensitive head, or any of its parts—no blotched and disfigured complexion—no prematurely lame and halting gait—no tremulous shaking of the hand, unable to carry a glass of water to the mouth without spilling it—no film and bleared-red about the eyes, nor bad taste in the mouth, nor tainted breath from the stomach or gums—none of that dreary, sickening, unmanly lassitude, that, to so many men, fills up and curses what ought to be the best years of their lives, without good works to show for the same—but instead of such a living death, which, (to make a terrible but true confession,) so many lead, uncomfortably realizing, through their middle age, more than the distresses and bleak impressions of death, stretched out year after year, the result of early ignorance, imprudence, and want of wholesome training—instead of that, to find life one long holiday, labor a pleasure, the body a heaven, the earth a paradise, all the commonest habits ministering to delight—and to have this continued year after year, and old age even, when it arrives, bringing no change to the capacity for a high state of manly enjoyment—these are what we would put before you, reader, as a true picture, illustrating the whole drift of our remarks, the sum of all, the best answer to the heading of the two last sections of our articles, and the main object which every youth should have, in the beginning, from the time he starts out to reason and judge for himself.