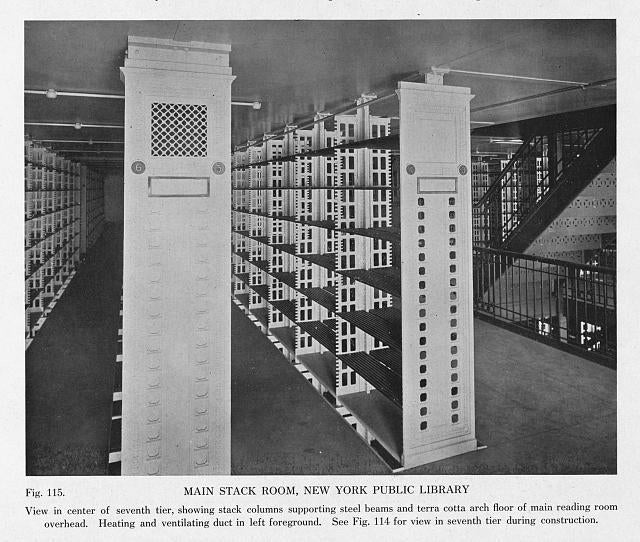

Before the early 20th century, public libraries typically used wooden bookcases with fixed shelves to house their volumes. In the 1910s, new public literacy initiatives like Andrew Carnegie’s library-building projects, as well as institutional expansions at the Library of Congress and many universities, drove the need for a different kind of library shelf. The new wave of libraries—bigger and more comprehensive than their predecessors—needed bookshelves that could accommodate their rapidly growing collections of books. The New York Public Library, for example, installed 75 miles of new bookshelves in 1910 in preparation of its grand opening the next year. And the shelves from earlier decades simply weren’t going to cut it.

So where were these new libraries going to get bookshelves that were up to the challenge? Snead & Company, of Louisville, Kentucky, was a cast-iron works business that manufactured everything from window frames to tea kettles to girders to spittoons. In the 1890s, the company took its expertise in metal work and turned its attention to the design of bookshelves, when it became apparent that metal shelves offered a unique solution to the turn-of-the century’s bookshelf crisis. From 1890–1950, Snead & Company designed, patented, manufactured, and installed an unprecedented measure of shelves, generating hundreds of miles of new shelf space.

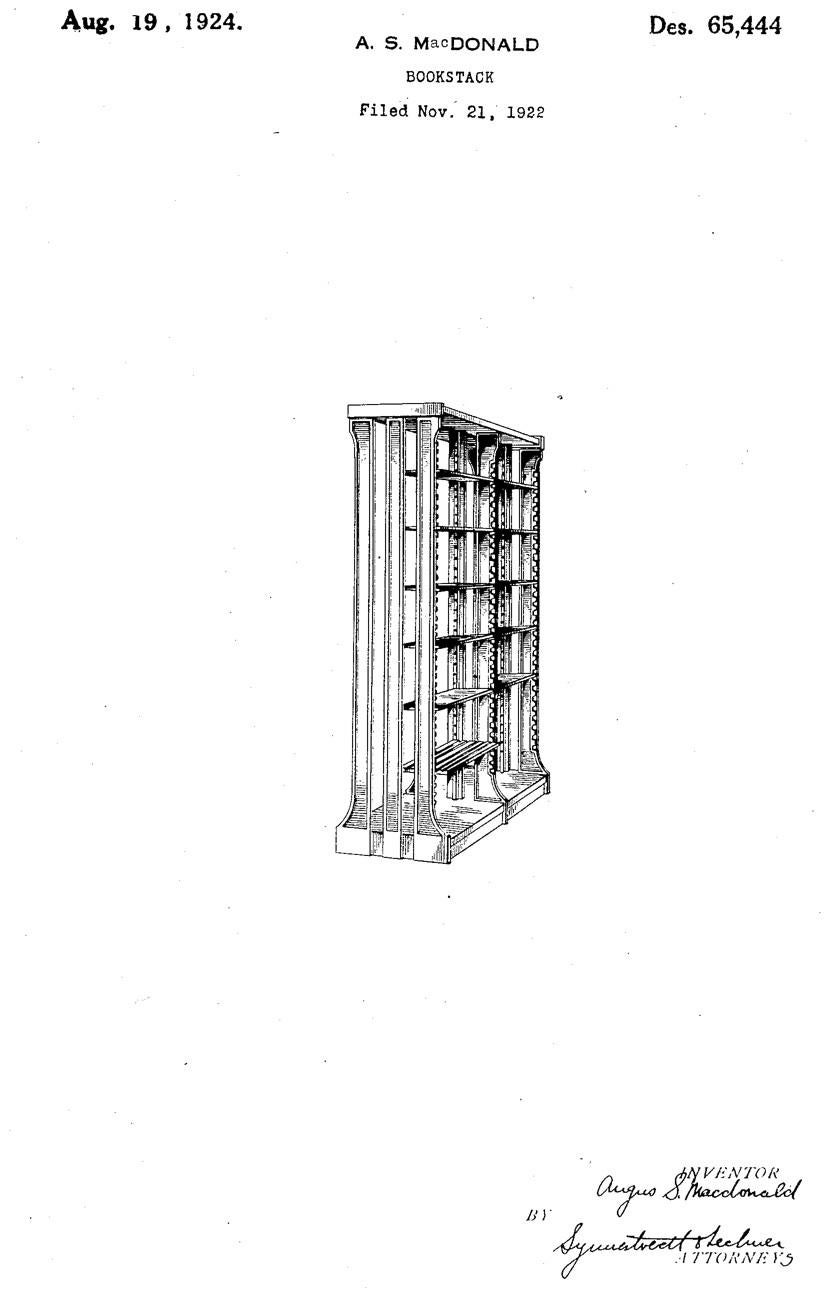

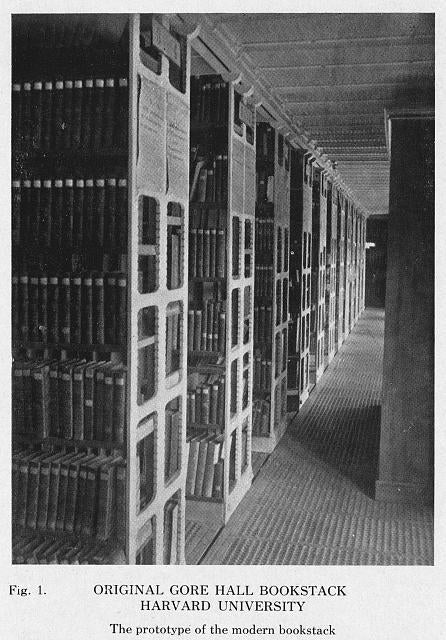

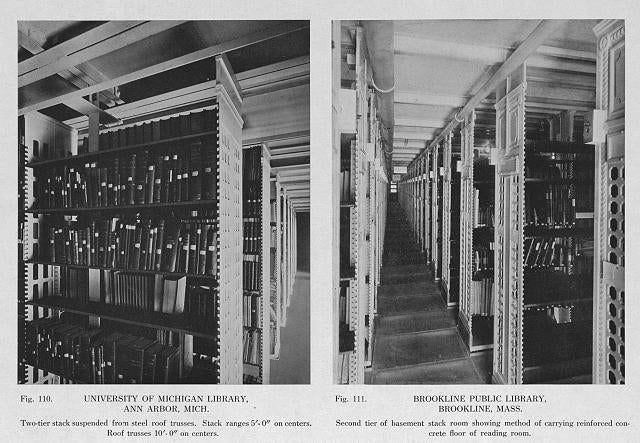

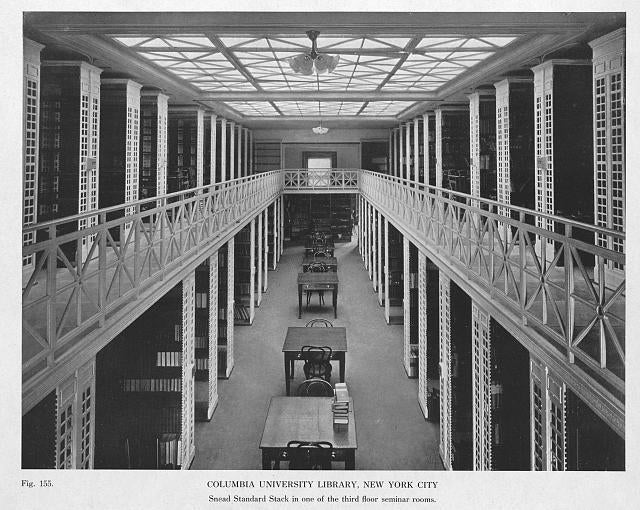

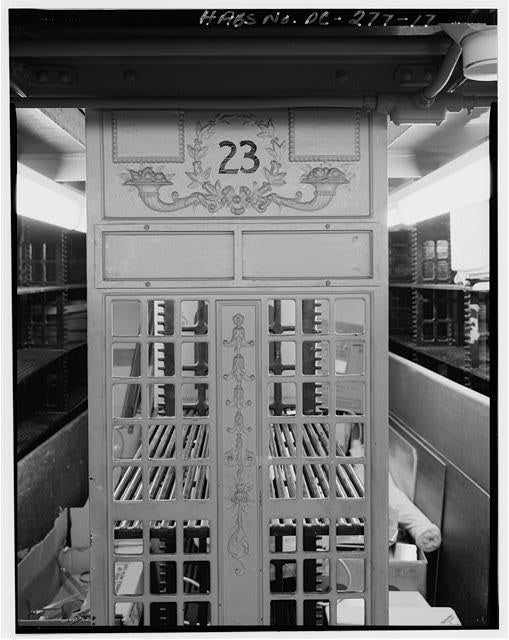

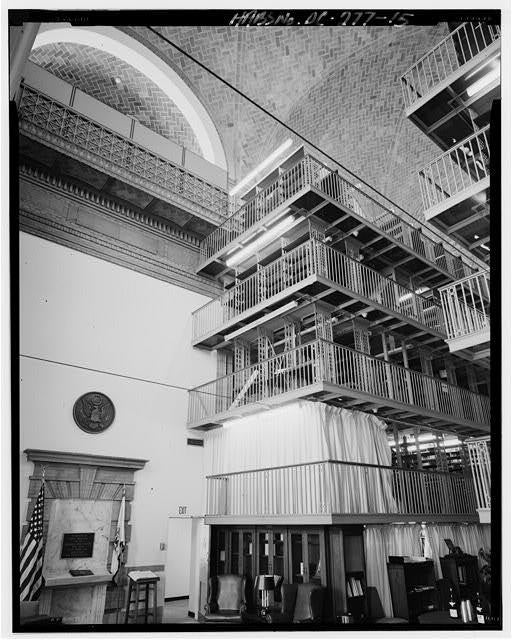

Snead shelves were multi-tiered, self-supporting bookstacks that, simply put, allowed more books to be packed onto more shelves. The bookshelves were architectural as well as aesthetic. Snead bookstacks were characterized by narrow aisles with very closely spaced shelves. The stacks rested on marble, glass, or slate slabs that were robust enough to support the massive weight of the shelves and the books they housed. The bookshelves had a “z” notch that would allow each shelf to be moved up and down to best deal with the height of the books being stored there. Early Snead bookstacks were built out of exposed steel or cast-iron columns that served as structural reinforcements for the building.

Snead & Company dominated the bookshelf industry for two generations. The company’s influence on the American bookscape diminished in the 1950s—due, in no small part, to the changing nature of library design, which de-emphasized large public institutions in favor of smaller library buildings. But Snead & Company’s behemoth bookshelves are still housing books at countless older libraries across the country, from the Library of Congress to University of Michigan.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Library of Congress