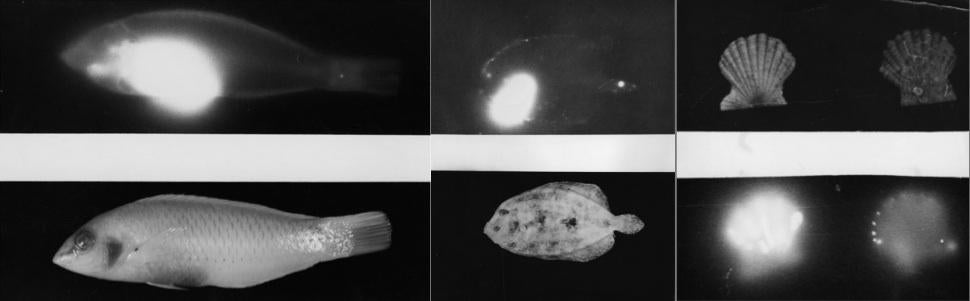

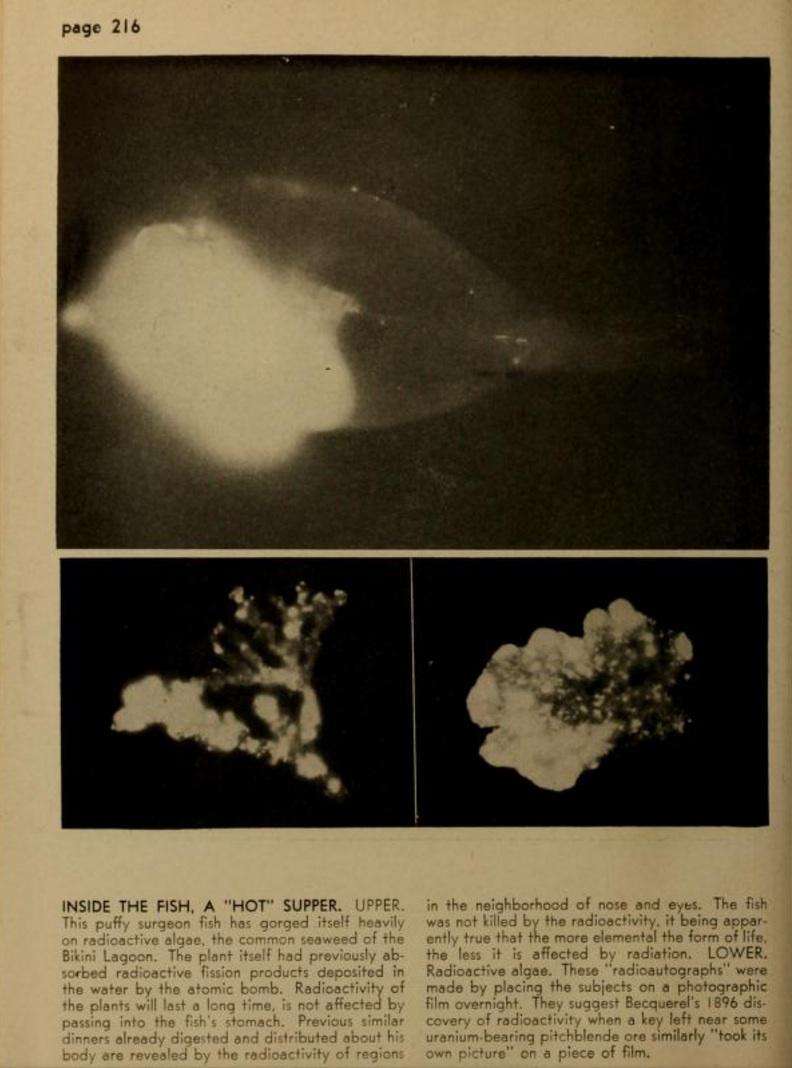

In June 1947, biologists from the University of Washington collected a wrasse from the waters around Bikini Atoll, squished it against a photographic plate, and took an x-ray. The resulting image shocked them. Almost an entire year had passed since the United States had detonated “Able” and “Baker,” two fission bombs, at the atoll. The scientists involved in the Bikini Scientific Resurvey were certain that the expansive Pacific Ocean would have quickly diluted and dispersed any radioactive products from the 1946 detonations.

And yet here, in dazzling white, was radiation revealed. Bikini Atoll’s biota had absorbed the products of the explosions. More curious, still: the radioactivity was not distributed evenly across a fish’s body. It seemed to be concentrated in the digestive system.

The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission was the main funder of ecological research in the United States from World War II until the 1970s. Between 1946 and 1962, the United States exploded 105 atomic and nuclear weapons in these inhabited Pacific atolls, changing their ecology, as well as the science of ecology itself. During this time the Commission continued to contract ecologists from the University of Washington and other institutions to return to the proving grounds.

The first studies done by the University of Washington Radiation Ecology laboratory—assembled by the Manhattan Project under strict confidentiality in 1943—had reflected the Manhattan Project’s belief that the major hazard of atomic technology was prolonged exposure to external sources of highly penetrative gamma radiation. The biologists burned specimens to ash and then passed those ashes through a Geiger counter. But during the Bikini Scientific Resurvey, they decided to employ a relatively new and more efficient method, “radioautography,” based on the assumption that a radioactive sample placed against photographic film would produce a brighter or darker image, depending on how much radiation reacted with the film.

Over the next two decades, such radioautographs led to the emergence of the idea that radiation is “biomagnified” as it moves up the food chain. This concept would prove essential to convincing legislators to ban DDT and restrict other pollutants. Interconnections among species—the objects of abstract flow charts in the 1930s—became brilliantly visible.

A number of other photos from the Pacific Surveys can be viewed at the University of Washington’s Digital Collection at this link.

Operation Crossroads: The Official Pictorial Record (New York: Wm. H. Rise & Co., 1946), viewable online here.