The “Moving Skeleton” announced its first appearance “To all Gentlemen, Ladies, and others, who are Lovers of Curiosities” in the London Daily Courant in September 1716. By a “Mechanical Projection,” the skeleton emerged from an upright case with a spring-loaded door. A curtain then slowly rose to reveal a full human skeleton, holding an hourglass in one hand and a dart in the other.

The Moving Skeleton joined a number of mechanical marvels on display in early-18th-century London’s taverns, coffee houses, and fairs, and was often displayed alongside that “wonderful Machine,” “Pinchbeck’s most surprising Astronomical and Musical Clock.” But as a (presumably) real skeleton, the attraction also had something in common with popular anatomical displays and models, including the infamous life-sized wax figure of a dissected pregnant woman that enjoyed a huge success in the 1730s.

The uneasy laughter that the Moving Skeleton evoked reminded its viewers that death was just around the corner. After the recurring outbreaks of plague the city endured in the 17th century, the disease struck Europe again in 1722, and although it did not reach Britain, it led Daniel Defoe to write his A Journal of the Plague Year (a fictional account of the 1665 plague) to remind Londoners of what could be in store for them.

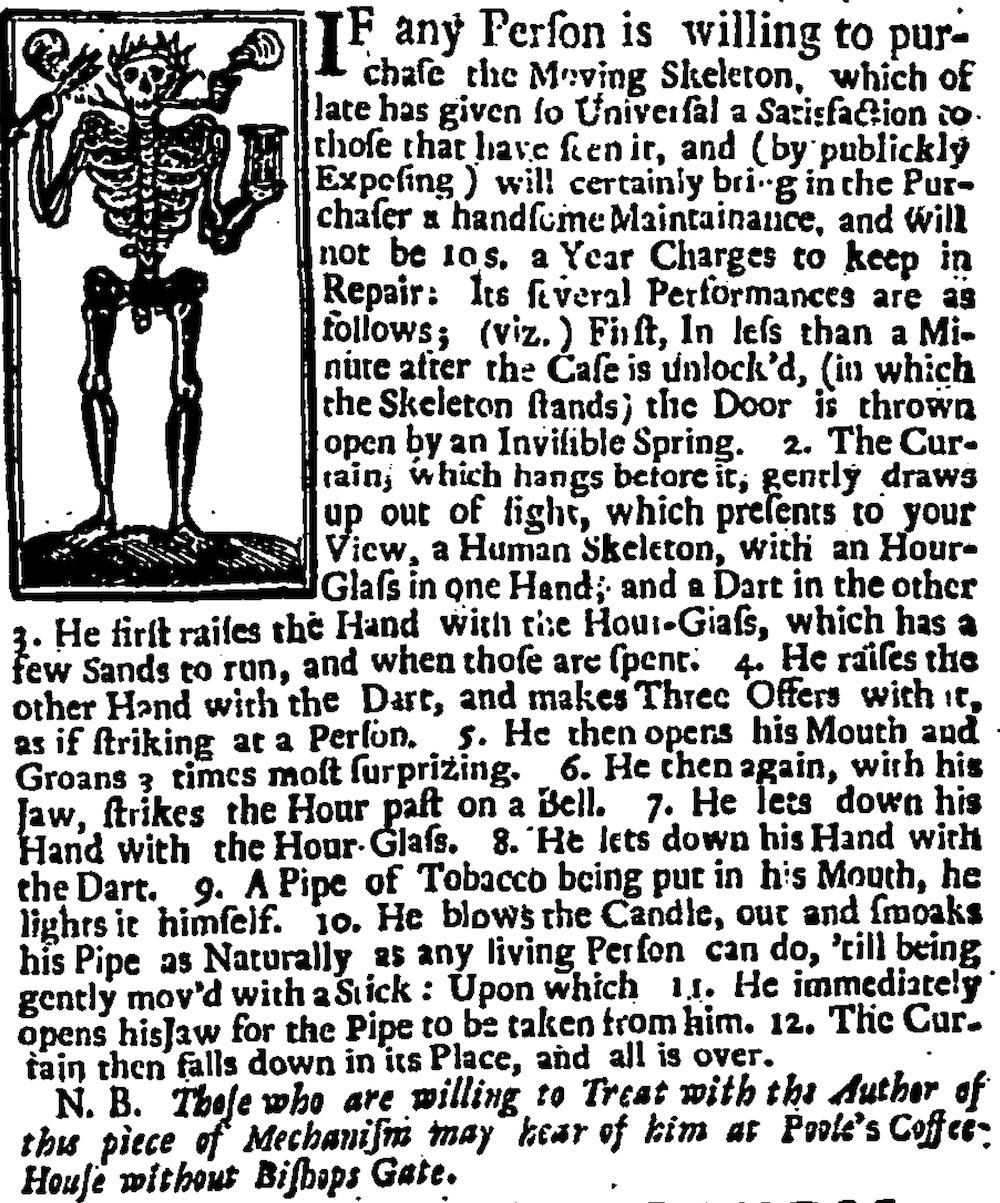

The Moving Skeleton made the rounds of London for about a year. This ad for its sale appeared in November 1717; “the Author of this piece of Mechanism” offered to meet prospective buyers at Poole’s Coffee House near Bishopsgate. After the publication of this ad, we hear no more of the Moving Skeleton.

Courtesy of the British Library