In 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed a network of dark streaks on the surface of Mars. He called them canali (meaning “natural channels”) and transposed them onto the first detailed modern map of the Red Planet. Because the English translation canal implies a manmade waterway, Schiaparelli’s drawings were misinterpreted as evidence for an intelligent Martian civilization that tapped polar icecaps to irrigate its barren landscape. The theory took off.

In the United States, amateur astronomer Percival Lowell spread this canal fever. After setting up an observatory on “Mars Hill” in Flagstaff, Arizona, in 1894, Lowell concluded that the canals were real and published his findings in three books. His alien vision, however inaccurate, excited a new wave of cosmic imagination. As Robert Markley writes in his book Dying Planet, “the canal thesis reignited debates about humankind’s place in the cosmos and thrust Mars into the forefront of controversies about ecology, evolution and social organization.”

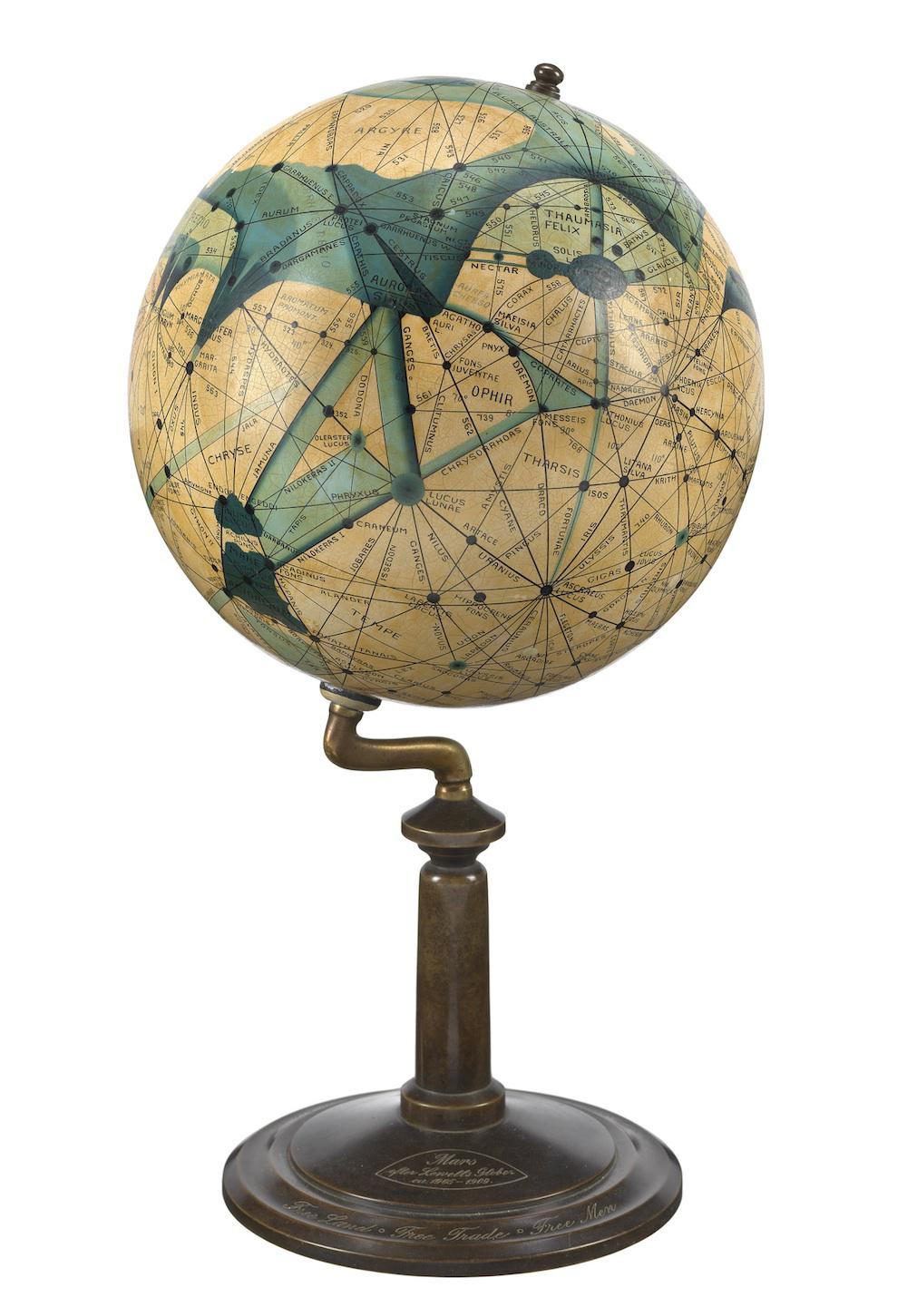

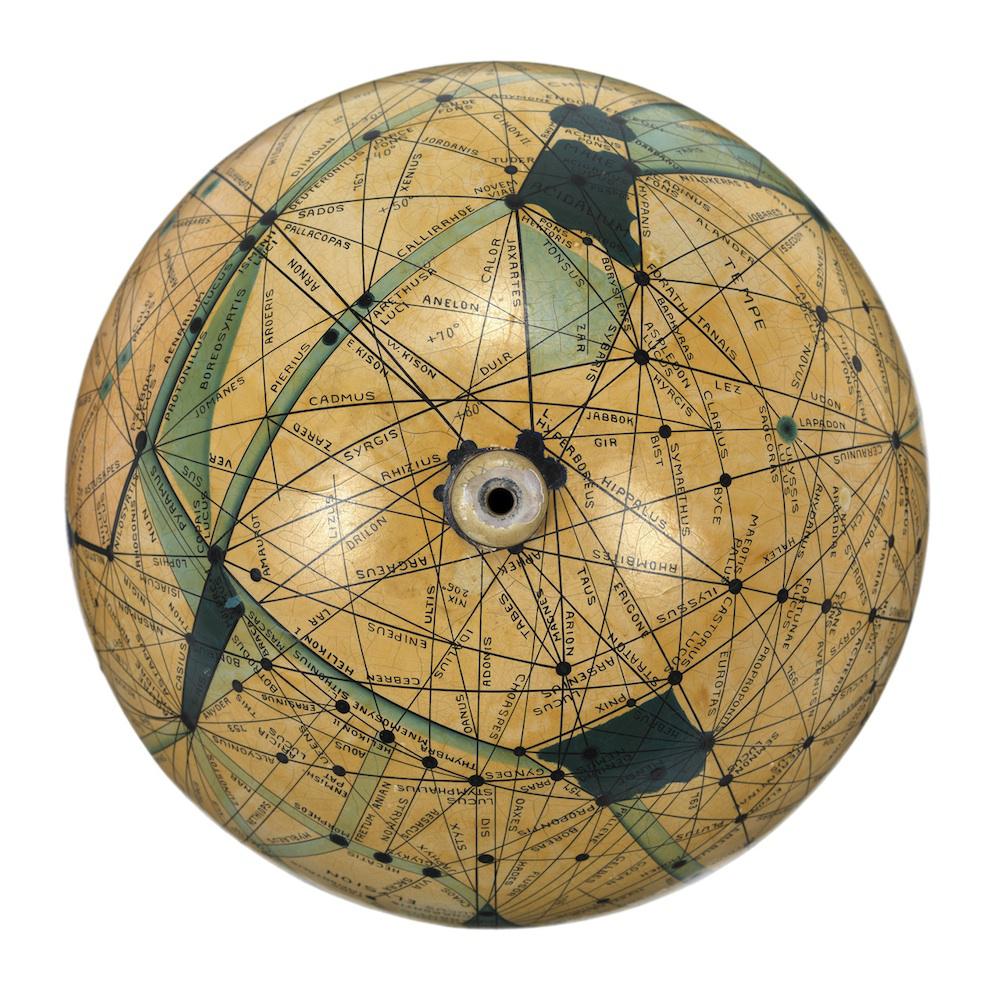

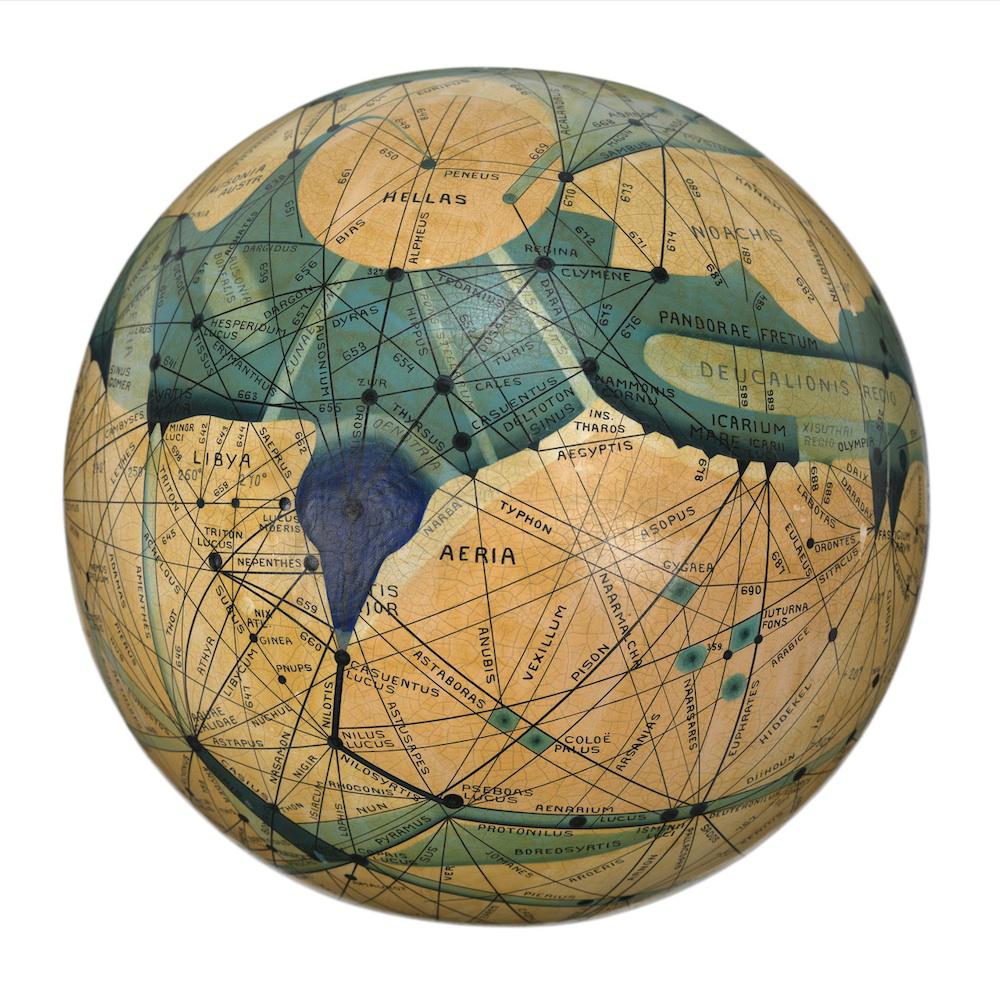

Emmy Ingeborg Brun, a Danish Mars enthusiast and socialist, was intrigued by Lowell’s vision of the planet’s infrastructure, which she thought was evidence of a radically different cooperative Martian social order. In 1909, Brun adapted Lowell’s maps and sketches into this handcrafted wooden globe. On the bronze base, Brun inscribed the socialist slogan “Free Land. Free Trade. Free Men,” as well as a quote from the Lord’s Prayer: “Thy will be done on Earth as it is in heaven.”

Although Schiaparelli and Lowell’s observations were mere optical illusions based on the human tendency to see patterns, they spawned one of the biggest detours in the history of the Red Planet’s exploration. While most astronomers had discarded the theory by the early 20th century, it wasn’t until NASA’s Mariner space missions in the 1960s and 1970s that the idea of the alien-made canals was formally debunked. There are no canals on Mars, but as we know now, there’s strong evidence that the planet contains liquid water.

David Westwood, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

David Westwood, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

David Westwood, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

David Westwood, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

David Westwood, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

David Westwood, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London