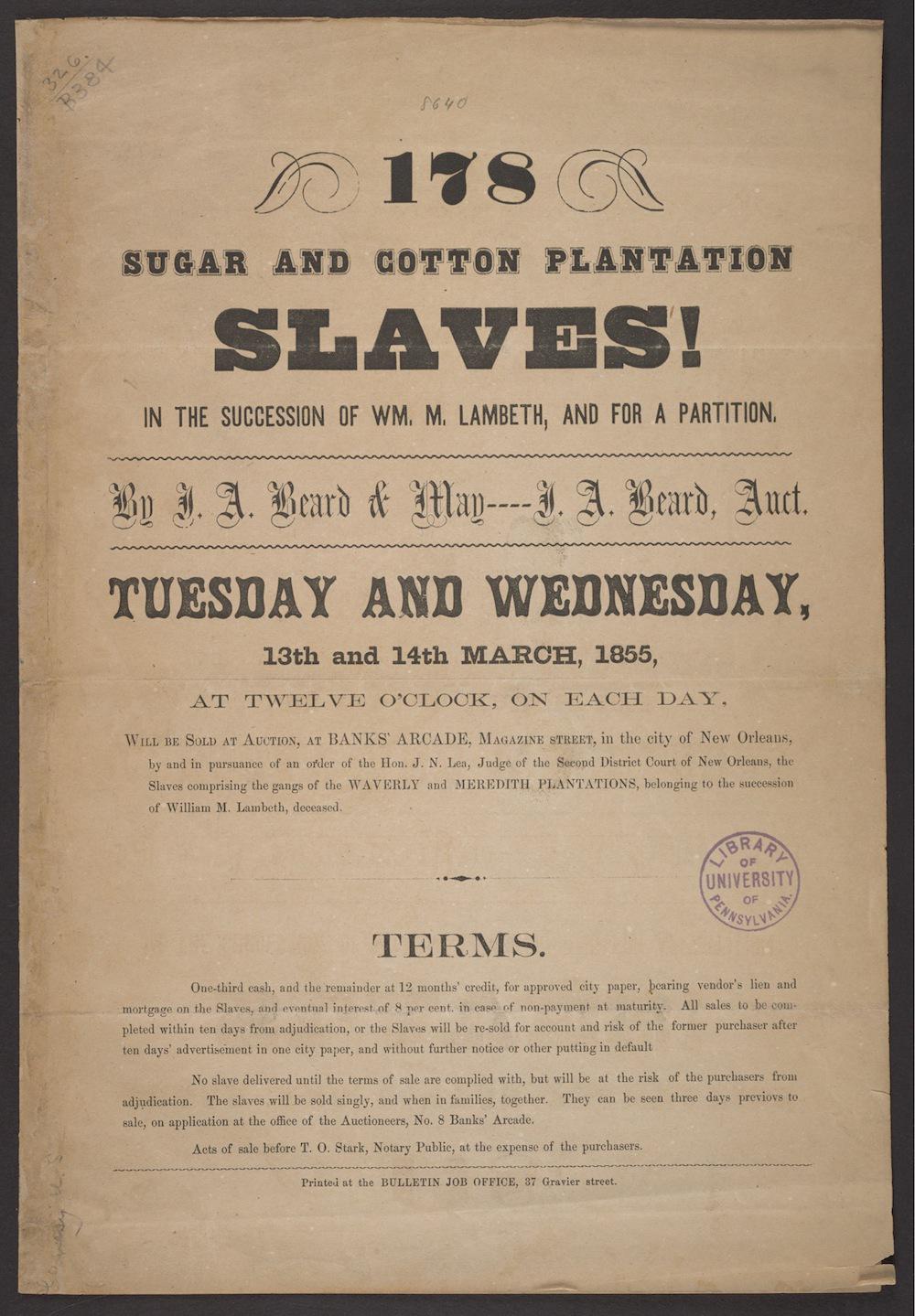

This 1855 brochure for a New Orleans slave auction staged by the firm of J.A. Beard & May shows how dealers represented the personal qualities, work history, and physical attributes of enslaved people who were up for sale. In this auction, two plantations’ labor “gangs” were to be split up and sold by the heirs of deceased planter and investor William M. Lambeth. (The brochure was digitized by the University of Pennsylvania Libraries, and is available via the Internet Archive.)

The “Terms” on the first page of the auction brochure show how the financial structure around purchasing enslaved people had evolved by the middle of the 1850s. Buyers doing business with Beard & May had to provide a down payment of one-third of the price, and could pay the remainder on credit; the seller would earn 8% interest “in case of non-payment at maturity.” For buyers who weren’t wealthy enough to buy people outright, an investment in enslaved property was a financial commitment.

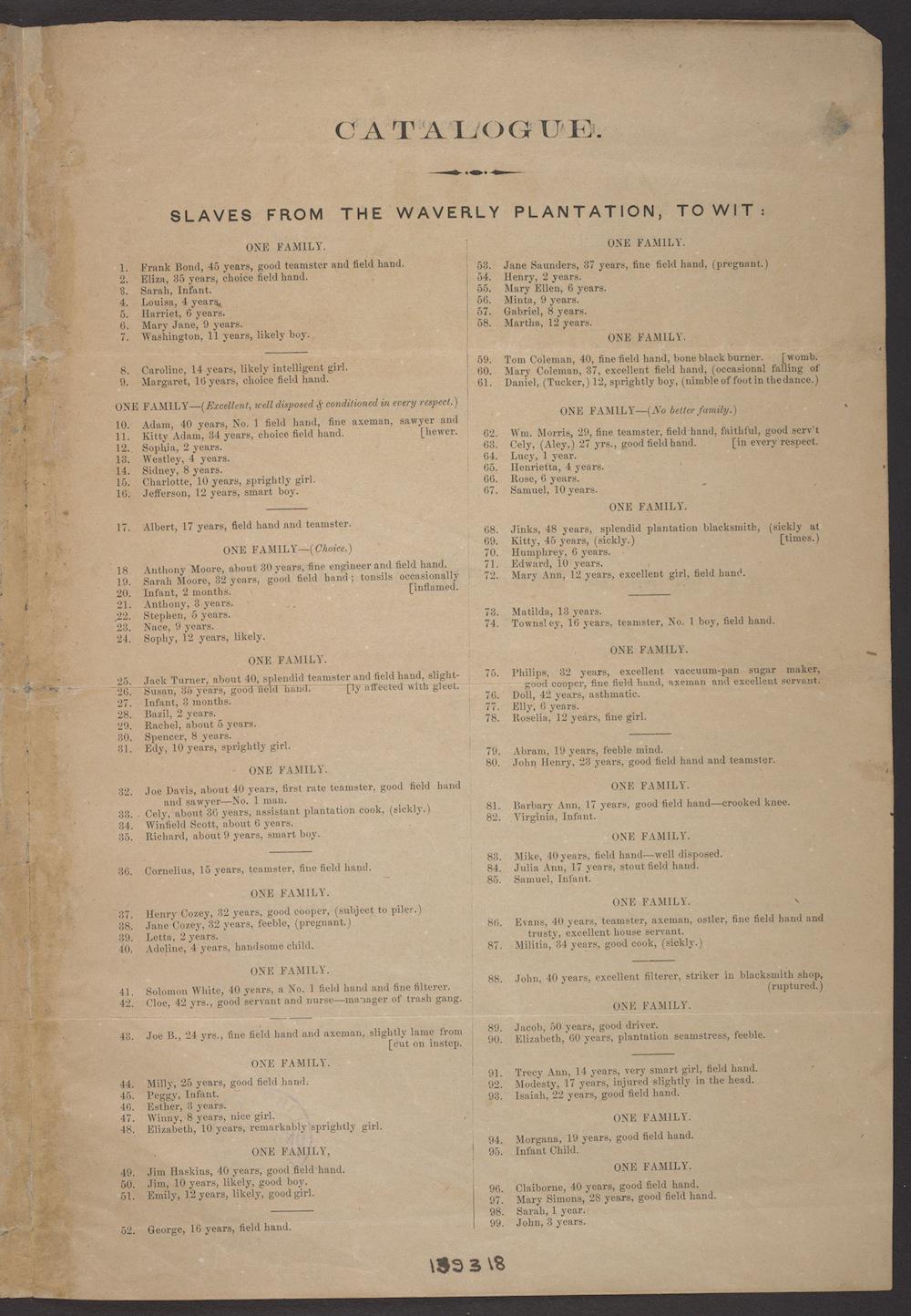

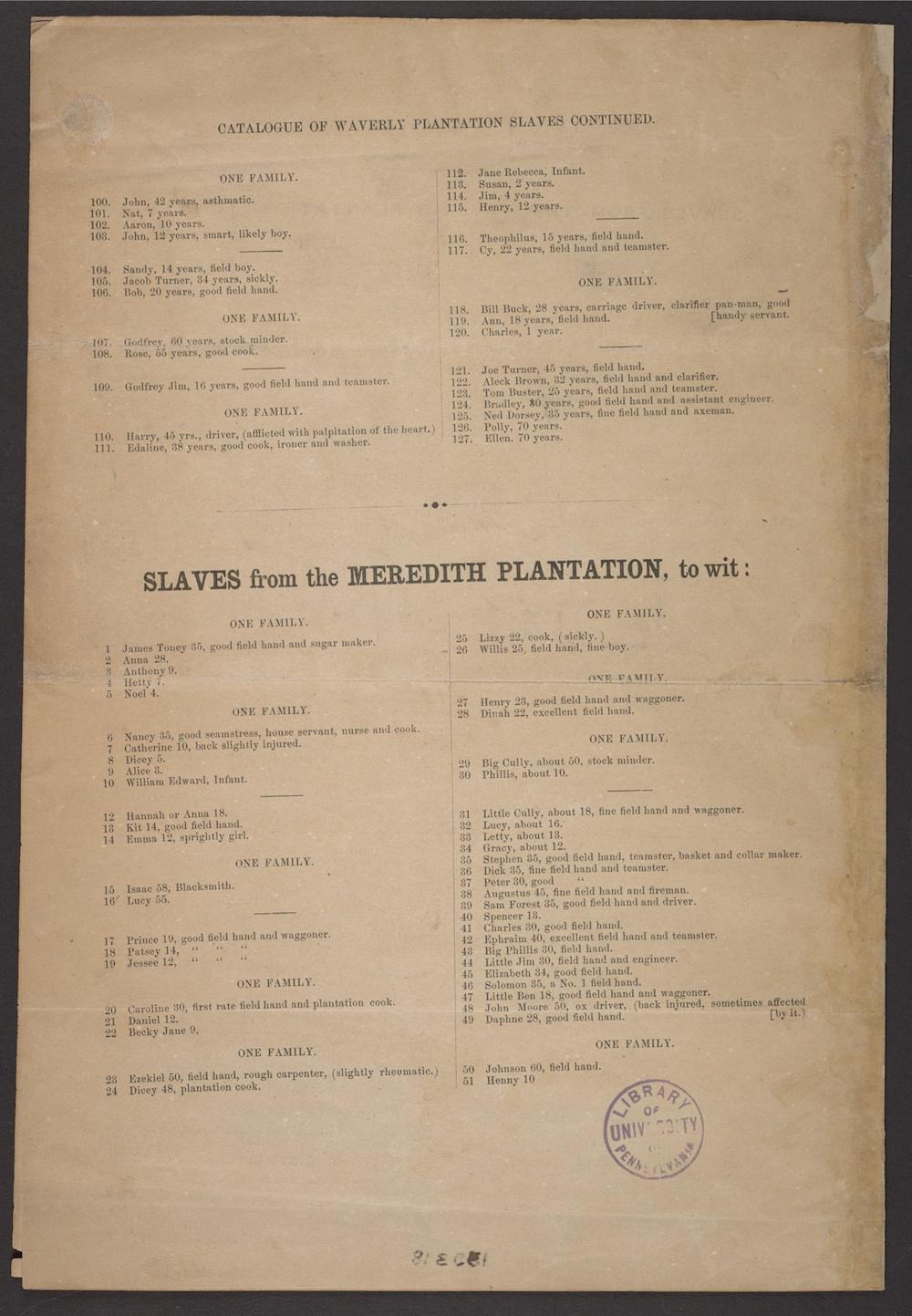

The auction brochure’s comments on health (“slightly lame from cut on instep”; “sickly”; “injured slightly in the head”) convey a reassuring sense of honesty in advertising. As historian Walter Johnson has written, buyers were suspicious of traders, and prided themselves on the ability to discern whether a person up for sale was “likely”—a word that could mean “strong,” “healthy,” “large,” or “willing to work.” Like other traders, Beard & May offered buyers access to the group before the auction, so that they could make their own evaluations by questioning and physically examining the people for sale.

Unusually, the people formerly owned by Lambeth were advertised for sale as family groups. Louisiana was one of the only states that had laws against selling very young children separately from their mothers—as historian Heather Williams writes, “the vast majority of enslaved children [in the United States] belonged to people who had complete discretion to sell them or give them away at will.” Even when an advertisement like this one stipulated that families were to be sold together, Williams writes, “the purchaser usually stood to make the final decision as to whether to take the whole group or only part.”

University of Pennsylvania Libraries, via Internet Archive.

University of Pennsylvania Libraries, via Internet Archive.

University of Pennsylvania Libraries, via Internet Archive.