The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

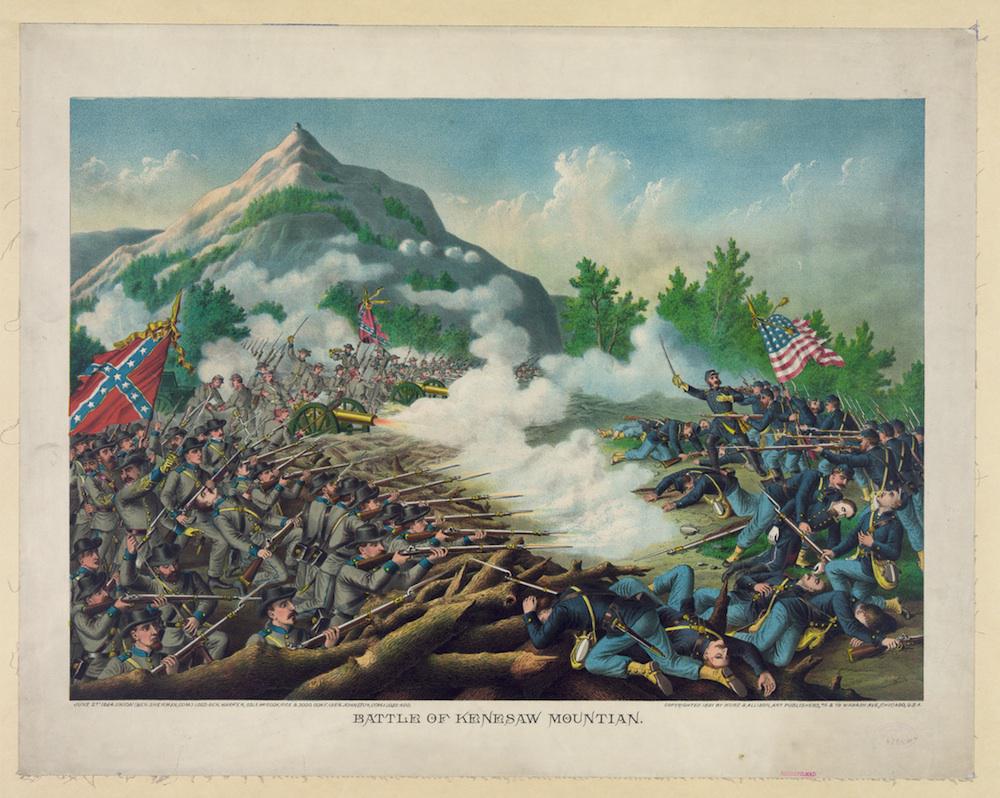

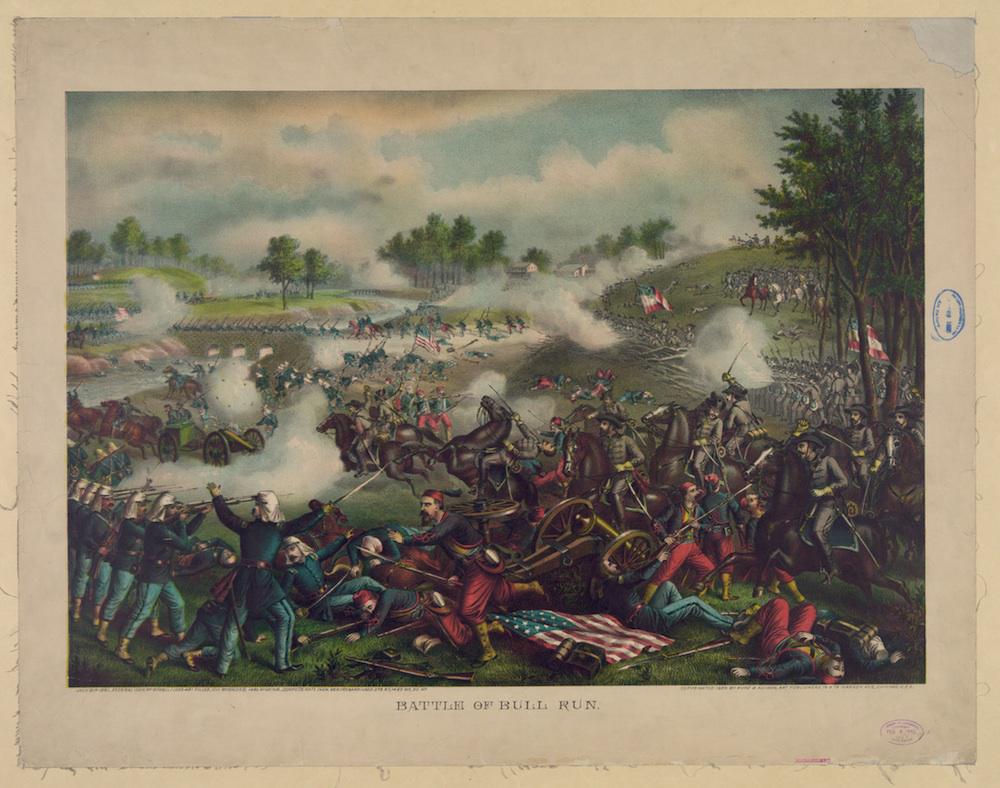

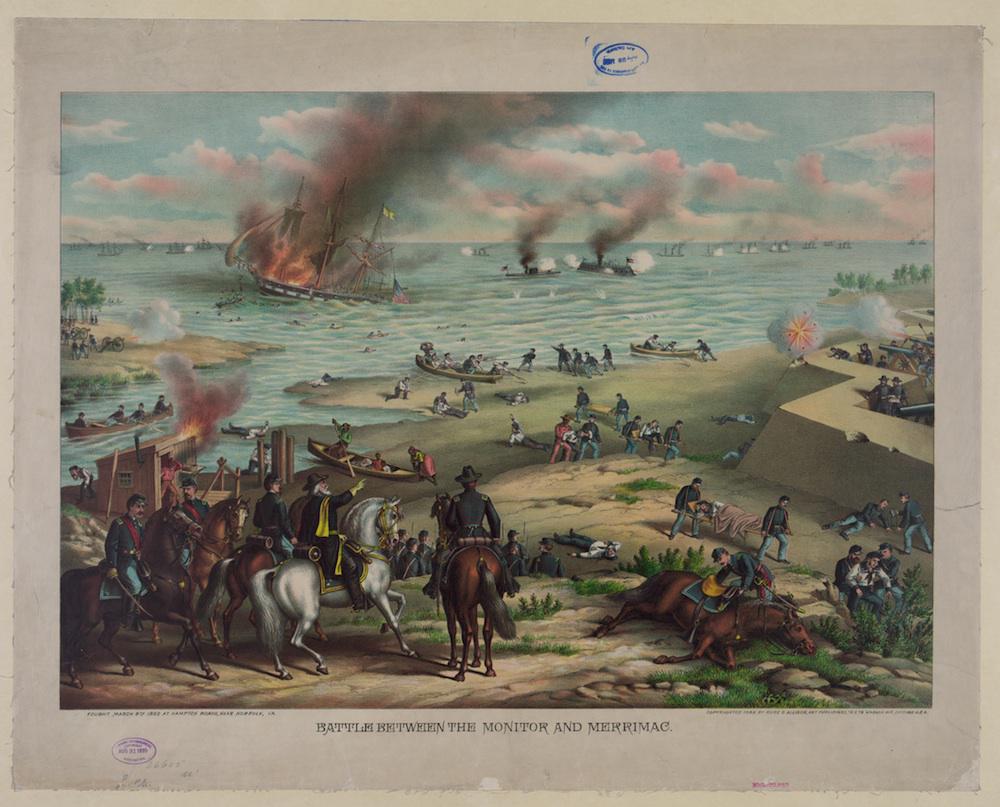

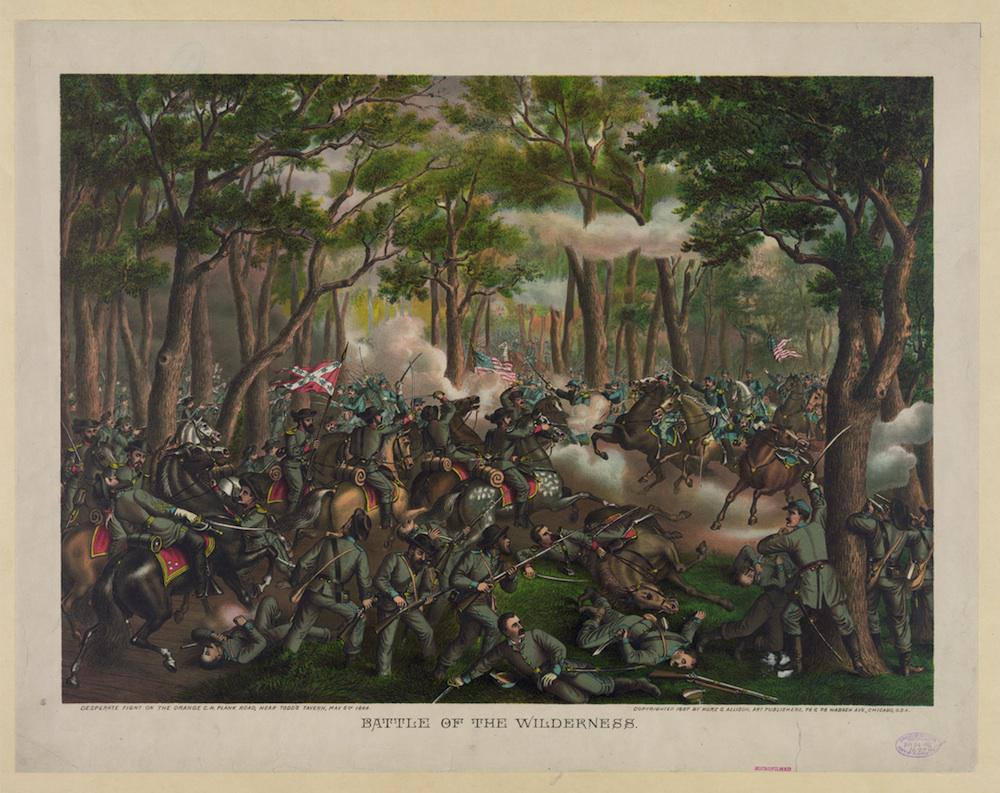

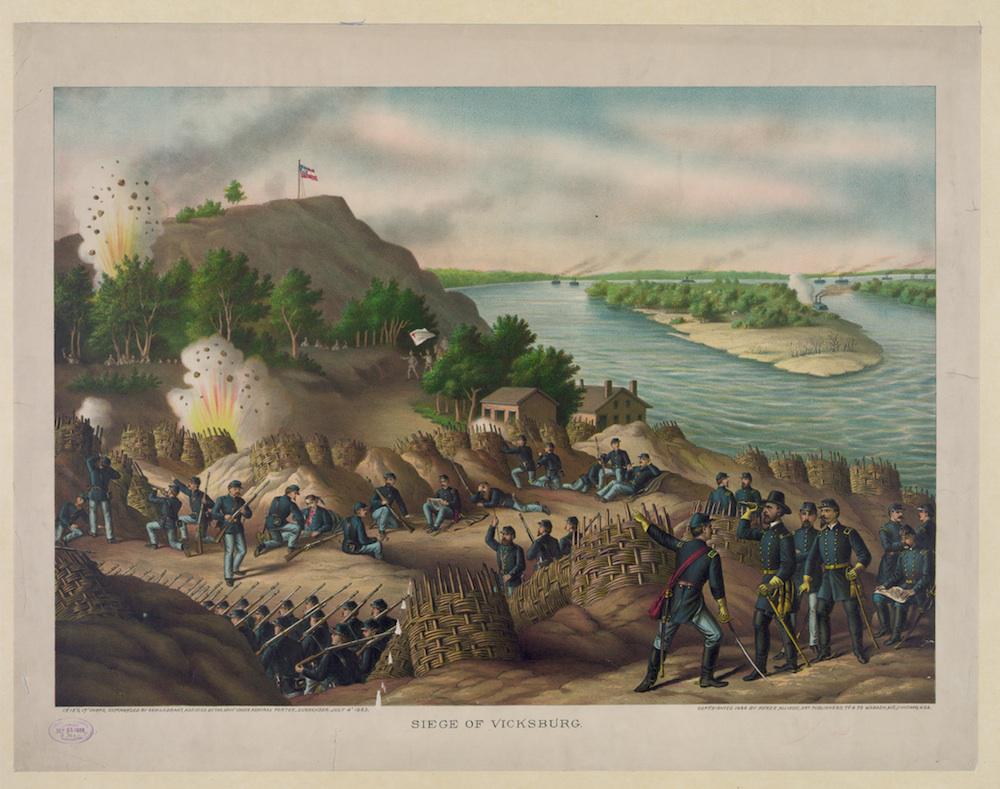

During the 1880s, Chicago printmakers Louis Kurz and Alexander Allison published During the 1880s, Chicago printmakers Louis Kurz and Alexander Allison published a series of 35 commemorative chromolithographs of Civil War battles. Twenty years after the end of the war, the collectible prints sold well; Americans eager for closure appreciated their heroic perspective on the conflict.

Comparing Kurz and Allison’s prints to other series of Civil War military art sold around this time, Mark E. Neely and Harold Holzer write that these works were almost “anti-photographic”: they favored a panoramic point of view and an idealized vision of soldiering. Neely and Holzer write:

Ill-fitting uniforms, slouching posture, imperfect and mismatched equipment, ordinary-looking men with jug ears and big Adam’s apples and crossed eyes—all the realities of military life revealed in photography—never enter Kurz and Allison prints.

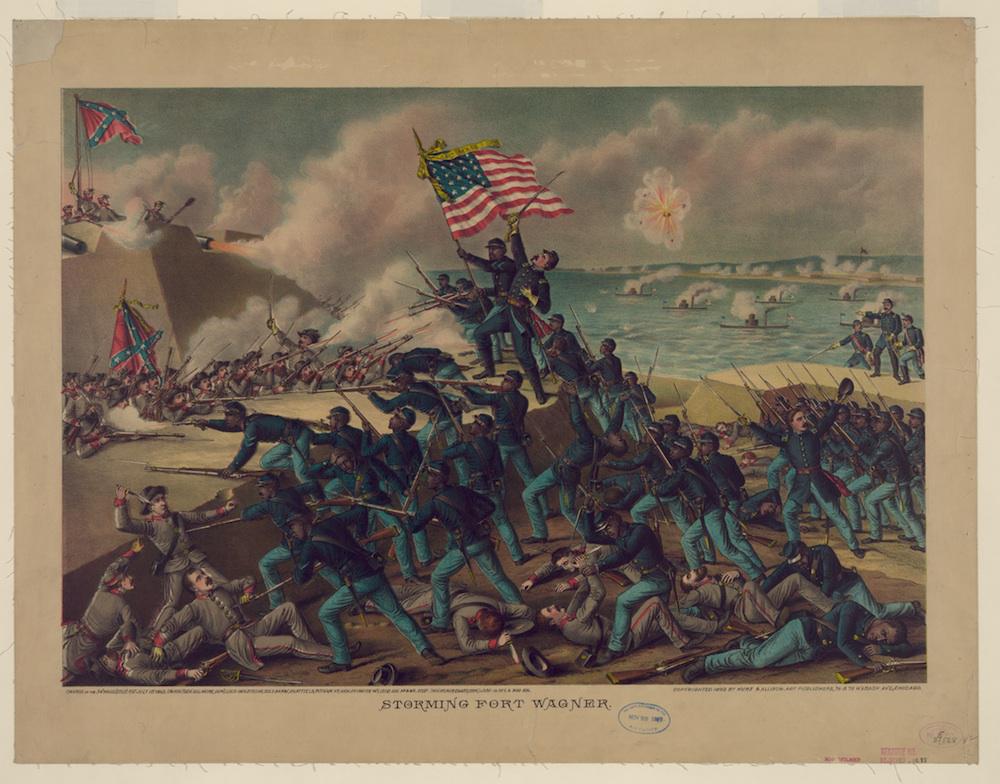

Kurz and Allison presented a stylized, sanitized vision of battle, but unlike some fellow late-19th-century printmakers who buried black contributions to the war effort in the name of sectional reconciliation, they didn’t shy away from representing black Union soldiers. (See “Storming Fort Wagner,” below; the print represents the soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts in a heroic light.) “This unusual subject matter is perhaps more remarkable than any other quality of Kurz and Allison’s work,” Neely and Holzer write, “and goes a long way toward making up for the firm’s many historical inaccuracies.”

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress.