The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

After emancipation, many freedpeople used newspaper advertisements to try to contact their family members. The Historic New Orleans Collection has made available a digital collection of more than 300 “Lost Friends” advertisements that appeared in the city’s Methodist Southwestern Christian Advocate newspaper between November 1879 and December 1880. The collection is searchable by name or location, but you can also browse advertisements at random.

In her book, Help Me To Find My People: The African-American Search for Family Lost in Slavery, historian Heather Williams writes that advertisements like these were an ad hoc community measure made necessary because the federal government was largely unprepared to help separated families reunite during Reconstruction. (Willliams was a guest on episode 4 of our Slate Academy podcast, the History of American Slavery; a few weeks ago, Slate published an excerpt from her book.)

Some agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau did work to help people find family, but there were many obstacles to the project, including a lack of financial resources to conduct searches and the scanty documentation kept by slave traders. The result was that many people were unable to reunite and placed newspaper ads for years after the end of the war—sometimes seeking relatives they hadn’t seen in decades.

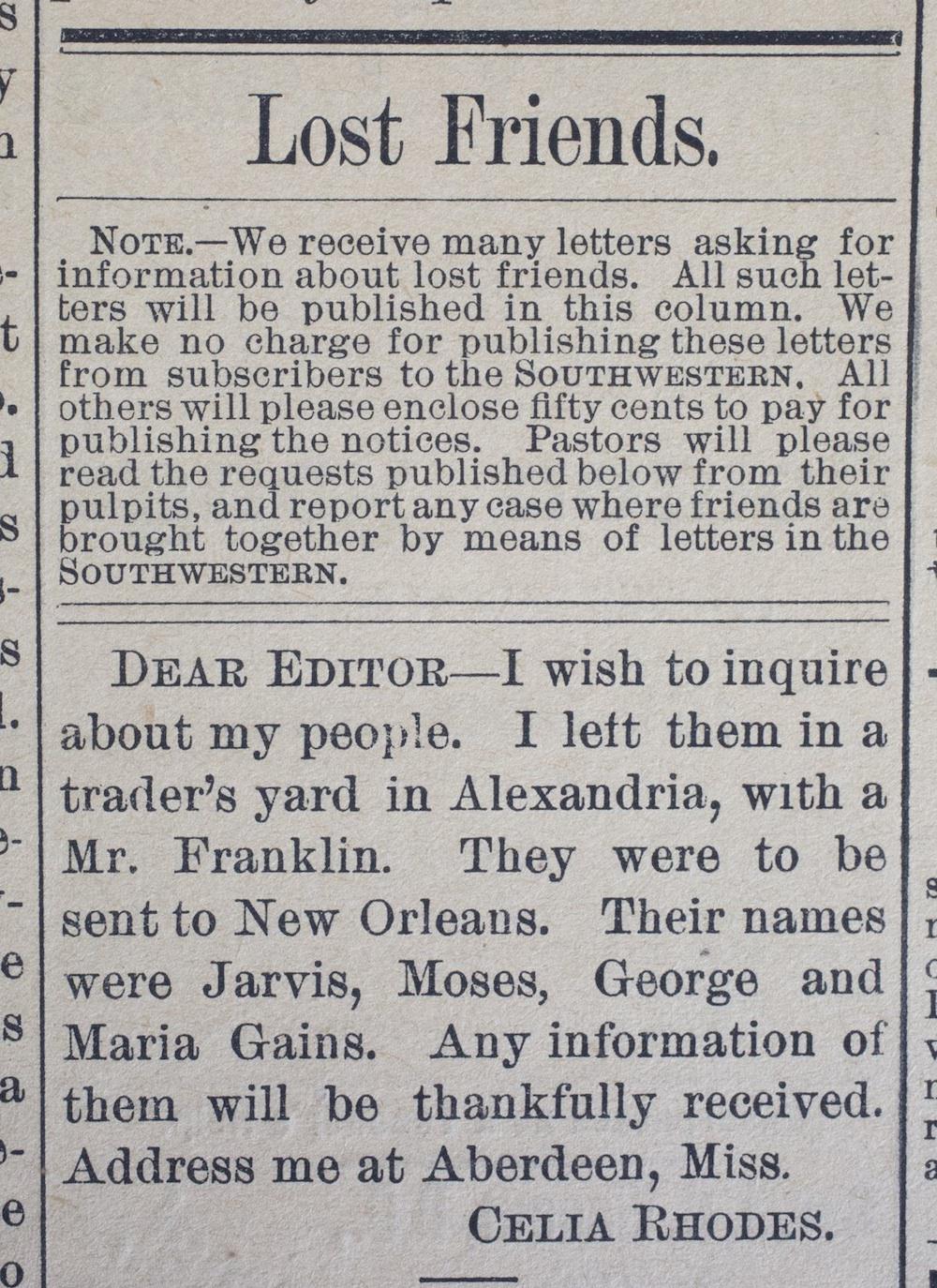

Historic New Orleans Collection/Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Libraries.

The Southwestern Christian Advocate prefaced each Lost Friends column with this announcement. Pastors expanded the reach of the printed advertisements by reading them in church. The 50-cent charge for the ad would have been no small matter. “Even at 50 cents,” Williams writes, “placing an ad required a significant monetary investment, as a recently freed person in the South could expect to earn between $5 and $25 a month as a field hand working six days per week.”

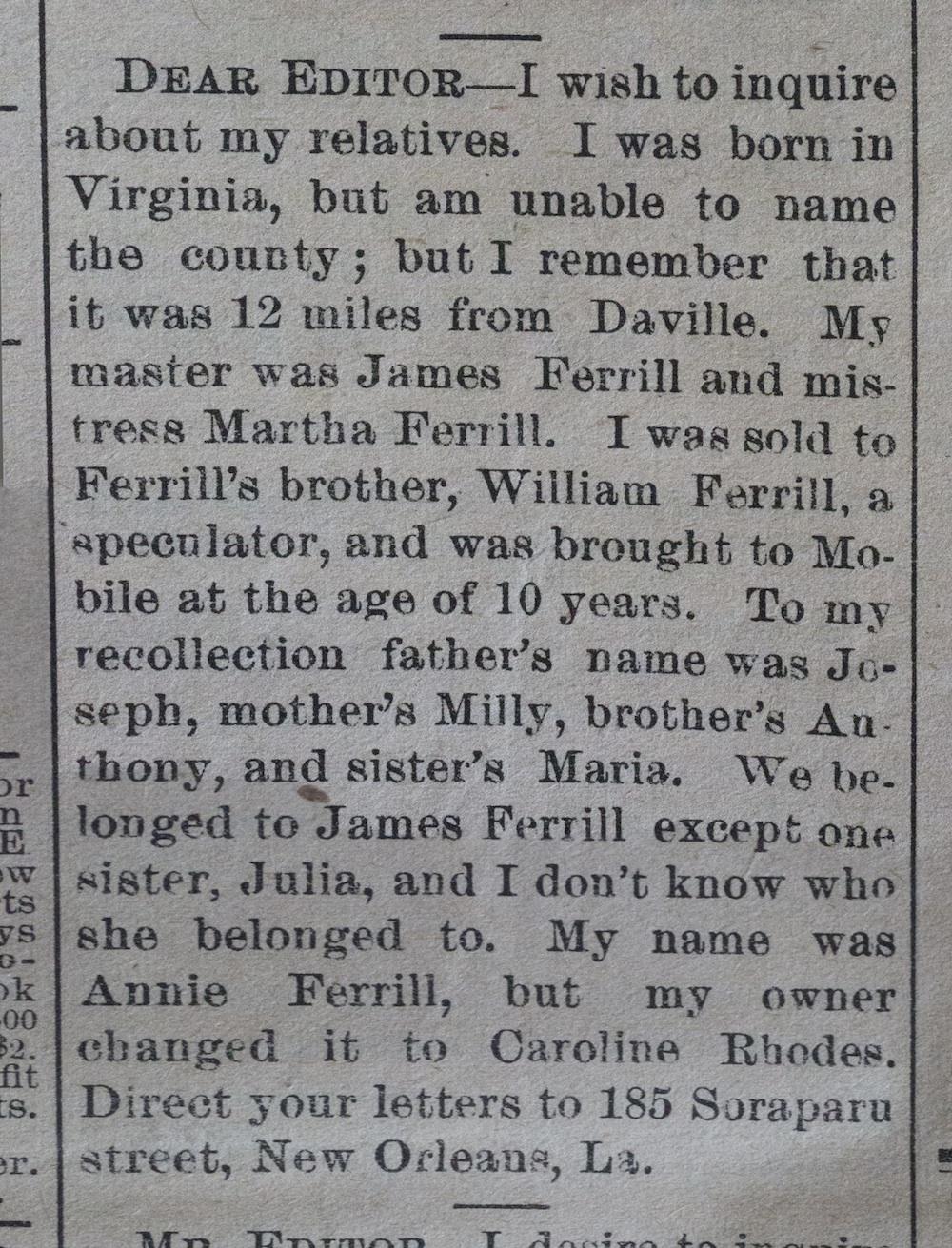

Historic New Orleans Collection/Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Libraries.

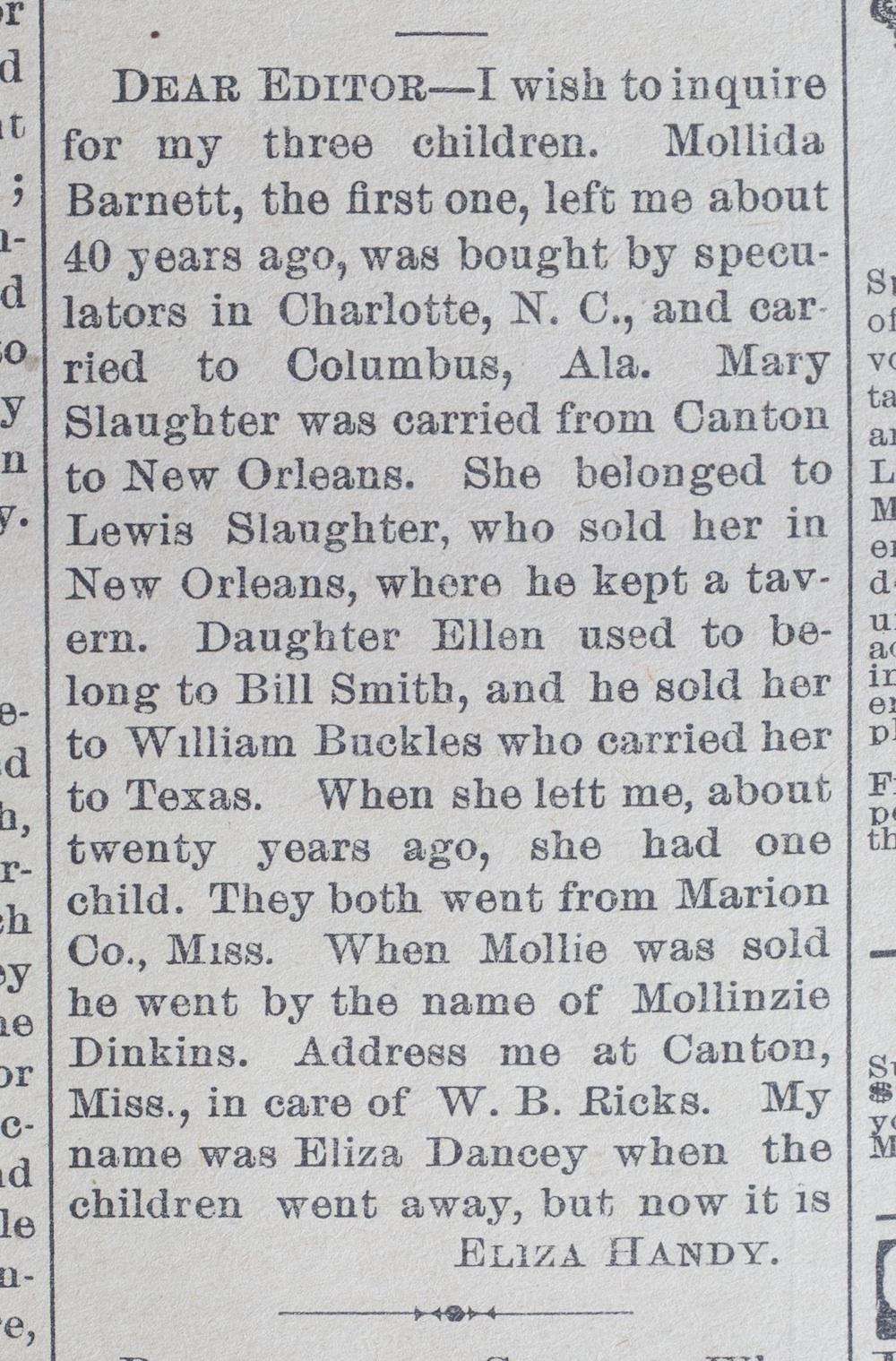

This advertisement shows how the prerogative of slaveholders, which allowed them to name and rename people at will, made it even harder to find separated relatives.

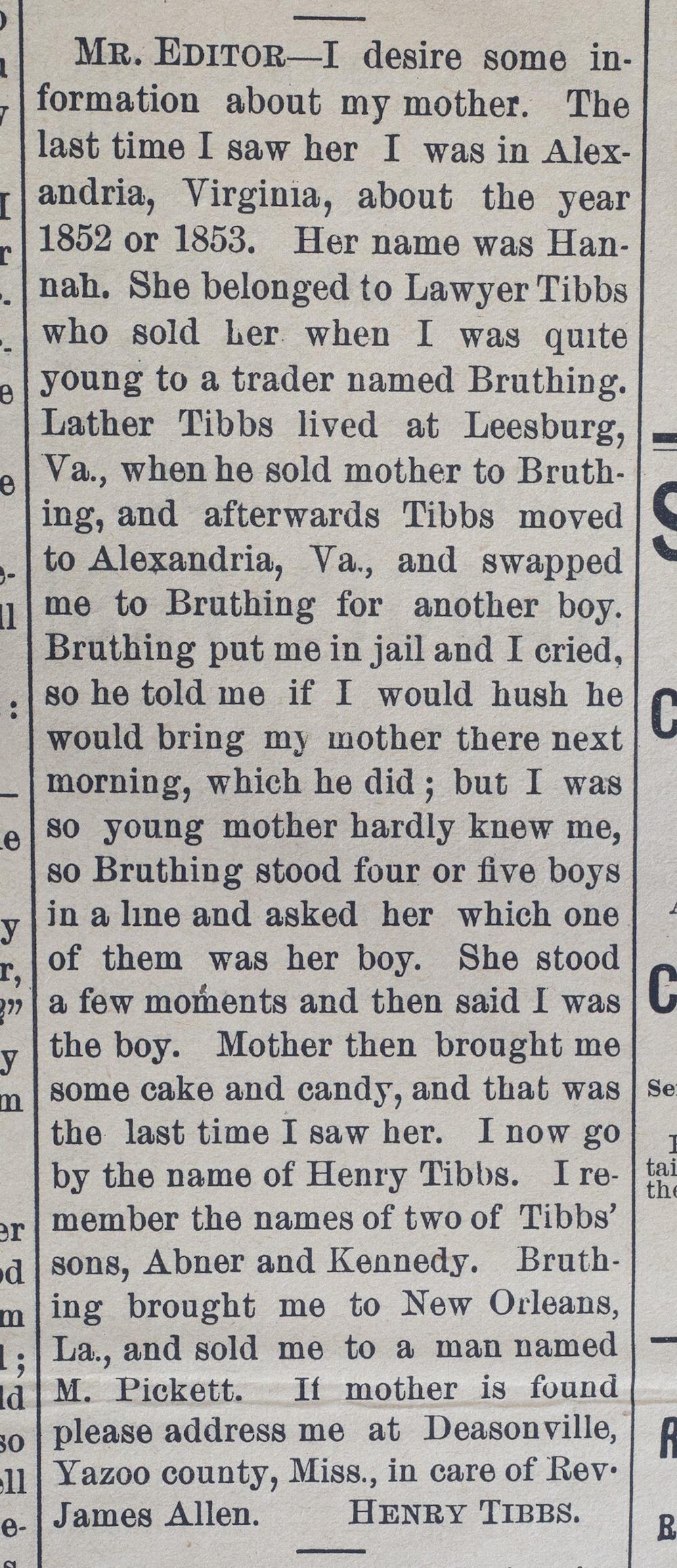

Historic New Orleans Collection/Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Libraries.

Henry Tibbs included an unusually detailed separation story in his ad. Williams writes that the placements seemed to serve two purposes—a way to find relatives and a “public airing of freedpeople’s memories and hopes.”

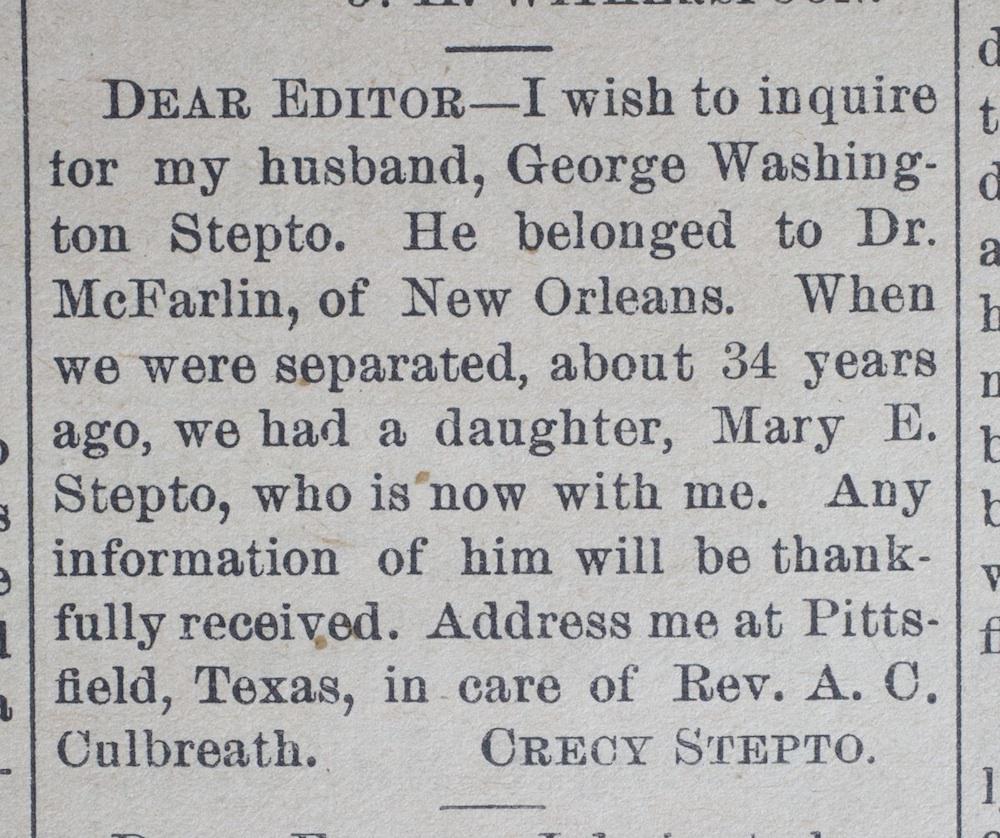

Historic New Orleans Collection/Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Libraries.

Crecy Stepto was looking for a husband last seen more than three decades before—a circumstance not unusual among those who chose to advertise. “It is likely that those who searched after a long time had created other significant relationships in their lives,” writes Williams. “They may have remarried or had other children, but the memories and the caring lingered.”

Historic New Orleans Collection/Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Libraries.

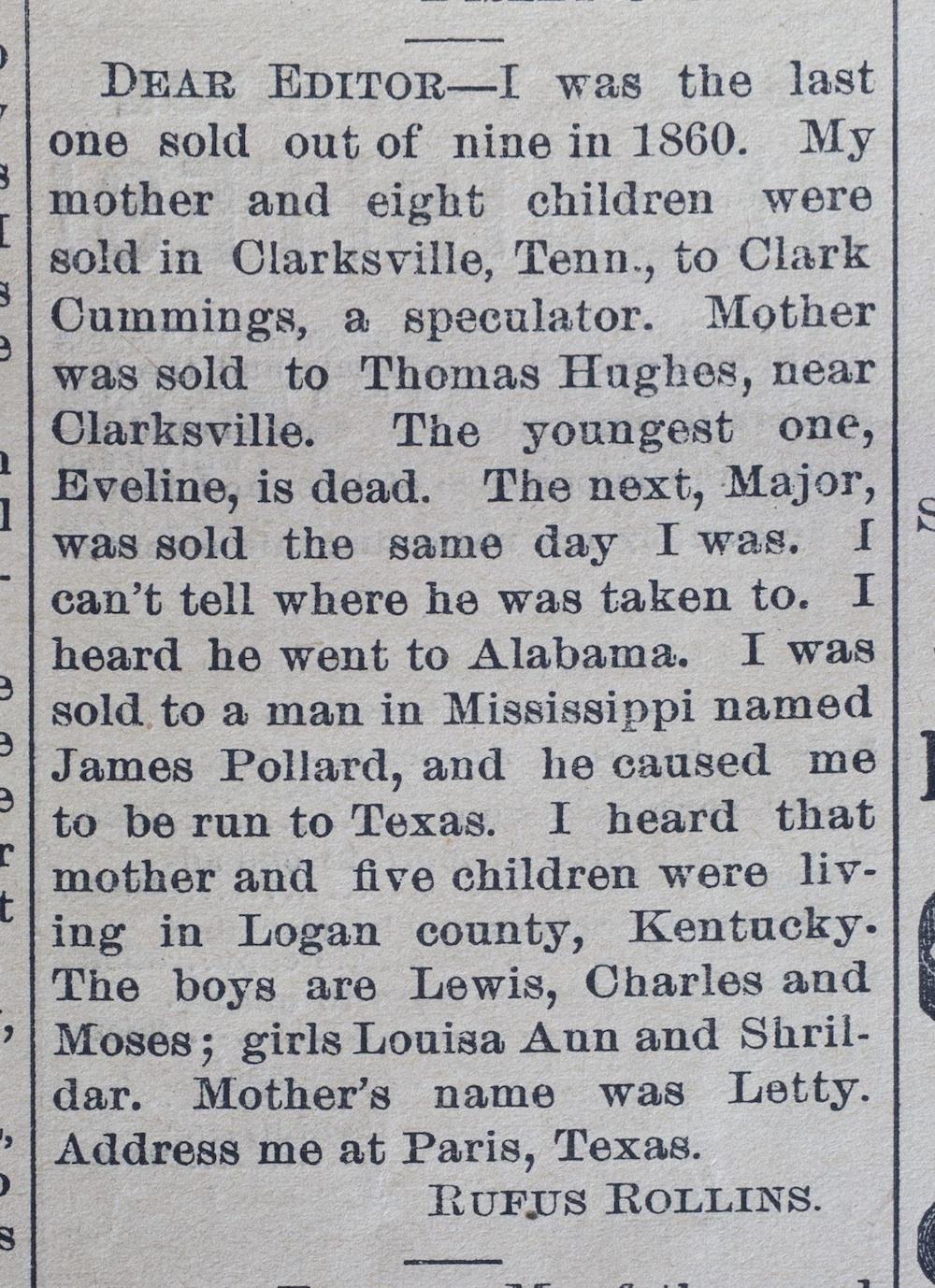

Rufus Rollins’ ad tells of a family separation that took place right before the war. He writes that he was “run to Texas”—an expression that might refer to the practice of “refugeeing” enslaved people during the war, or removing them to places far away from the reach of the Union Army.

Historic New Orleans Collection/Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Libraries.

Williams writes that she was able to find only a few instances of successful reunions coming from the placement of a newspaper ad. Every once in a while, however, it worked. The Christian Advocate wrote about one such result in 1877. “We published in this column a letter from Charity Thompson, of Hawkins, Texas,” the editors reported in March of that year. “The letter … was read in the First Church Houston, and as the reading proceeded a well-known member of the Church … broke into tears and cried out ‘That is my sister and I have not seen her for thirty three years.’ The mother is still living and in a few days the happy family will be once more re-united.”