The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

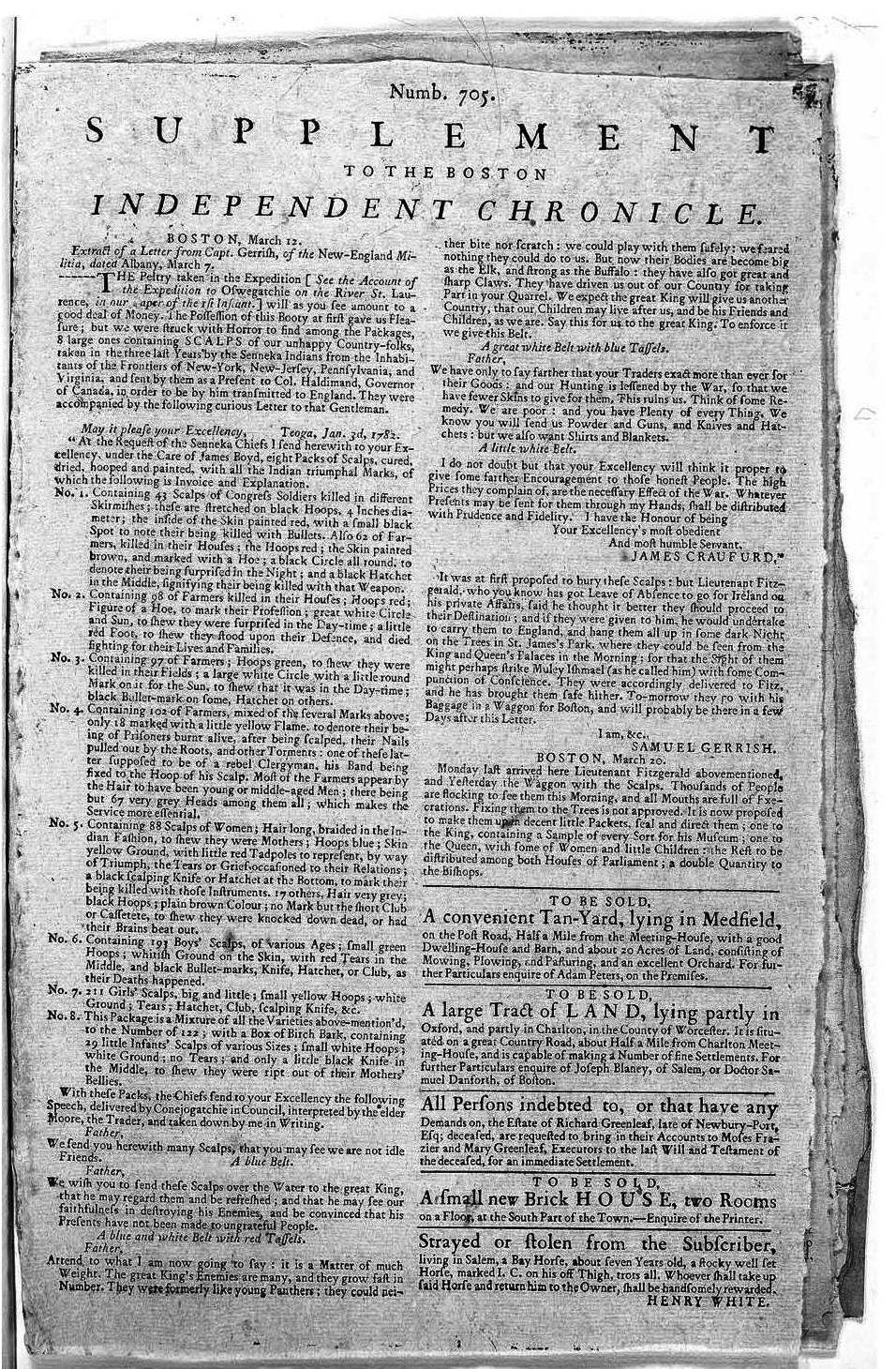

Benjamin Franklin wrote and published this hoax, “Supplement to the Boston Independent Chronicle,” in 1782, hoping that it would end up in the hands of British newspaper editors who might reprint articles from its pages. Through these manufactured tales of atrocities perpetrated by Native Americans at the behest of the British, Franklin looked to influence the mindset of the British public as he worked on negotiating the peace treaty that would formally end the conflict between Britain and the new United States.

Franklin penned the letter that takes up three-quarters of the page below using a set of narrative framing devices. Most of the text is written in the voice of a “British agent,” James Craufurd, who addresses the governor of Canada, presenting him a shipment of colonists’ scalps taken by “Senneka Indians” loyal to the crown. Franklin embedded this letter within another, from Samuel Gerrish, a captain in the New England militia. The fictional voice of “Gerrish” presents the Craufurd letter, purporting to have captured it along with other British military goods.

The description of the scalps includes gruesome and colorful details about the manner in which farmers, mothers, boys, and girls were killed: “102 [scalps] of Farmers…; only 18 marked with a little yellow Flame, to denote their being Prisoners burnt alive, after being scalped, their Nails pulled out by the Roots and other Torments…”

Both colonists and their British opponents had enlisted the help of local Native American tribes in the conflict. Yet, literary historian Carla Mulford writes, “Franklin had probably become aware during his years of diplomacy that the general population in England and Europe was relatively unaware of this situation.” In the Supplement, Franklin exploited this lack of awareness by ratcheting up the level of drama. Since Franklin was looking to secure reparations for colonists who had suffered Iroquois attacks, the atrocities reported in such vivid color in the letter would, he hoped, sway British readers to support that objective.

Mulford found evidence that the scalping letter was reprinted a few times in London, and many more in the new United States. Thirty-five American newspapers republished Franklin’s handiwork as truth before 1854, when the Trenton, New Jersey, State Gazette outed it as a hoax.

You can see the two other pages in Franklin’s Supplement, including a letter supposedly from John Paul Jones protesting the treatment of American prisoners of war, reproduced in Mulford’s essay. I first read about this hoax on the website of the Journal of the American Revolution.

Image courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.