The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

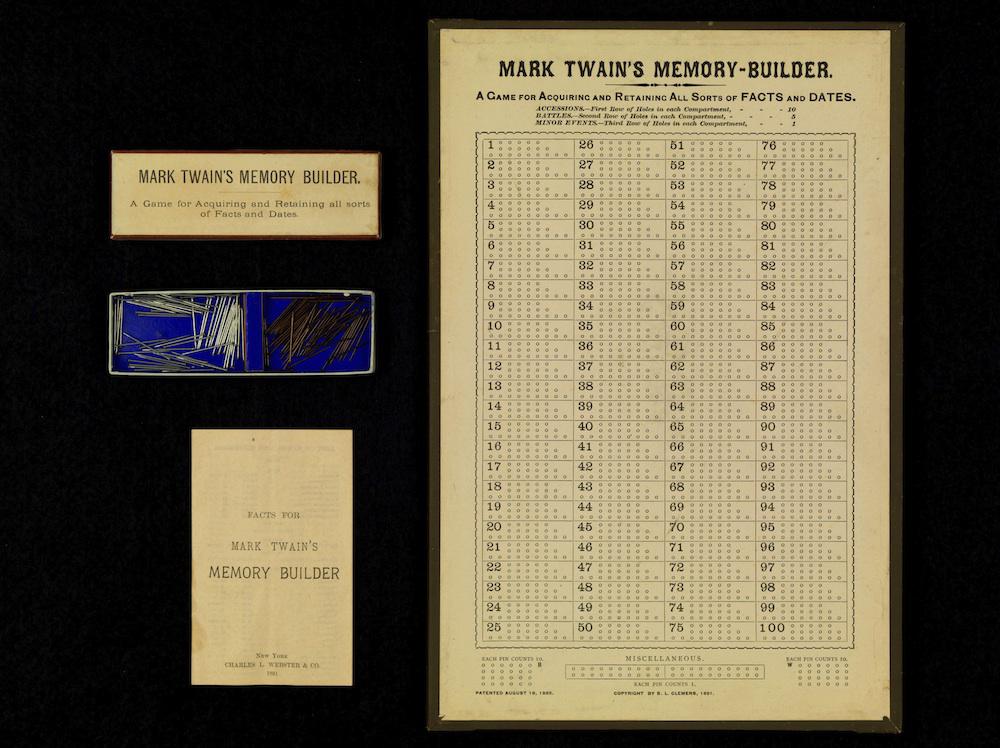

This game, patented by Mark Twain in 1885, is a learning aid meant to help students practice historical knowledge. Professor of English Stephen Railton writes that Twain, an amateur inventor who came up with the idea for the game while finishing the manuscript of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, “conceived the game as a way to help his daughters learn historical dates, but it quickly grew in his mind into a marketable commodity.”

Twain believed that memorization—a common strategy of 19th-century schooling—was a worthy, if tiresome, pursuit, and looked for ways to make it more interesting for annoyed students. In a 1914 piece for Harper’s Monthly Magazine called “How to Make History Dates Stick,” Twain spoke to children frustrated with the need to know dates, arguing for their importance: “They are like the cattle-pens of a ranch—they shut in the several brands of historical cattle, each within its own fence, and keep them from getting mixed together.” The visual methods of memorization that Twain outlines in that piece are another iteration of the principle behind this game.

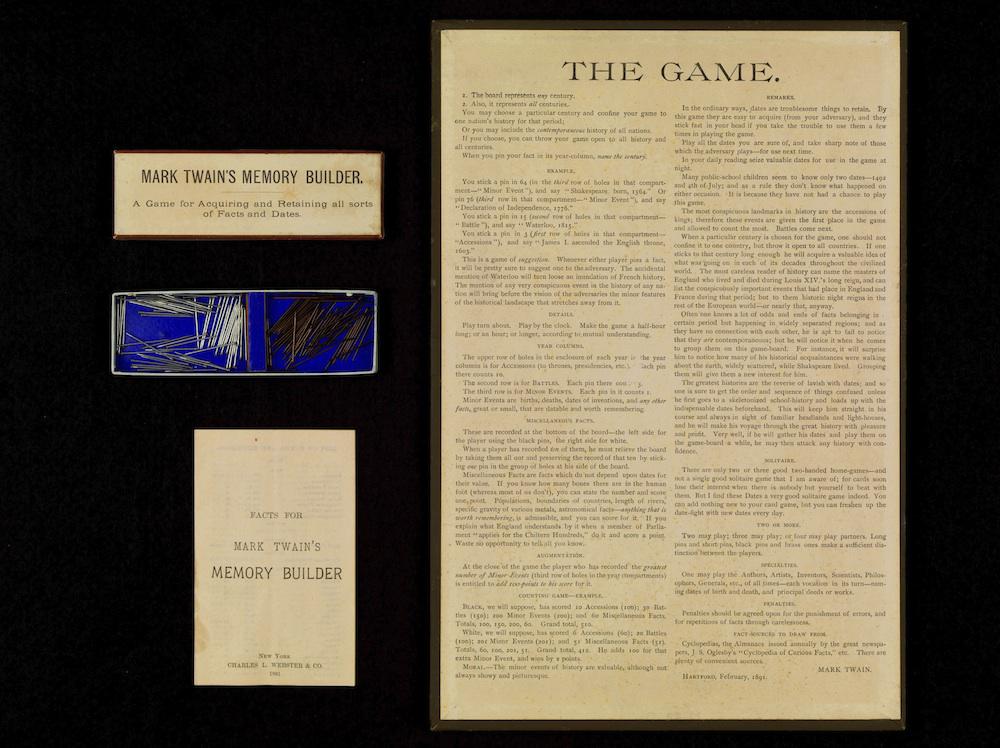

The game came with a packet of pins, half of which were colored black in order to differentiate between teams. Players would select a century to play, and decide whether to confine themselves to the history of a single nation. (Players could make it easier on themselves by picking multiple centuries or multiple nations; at its broadest, the game could encompass all nations and all times.) Then, going back and forth, they would name events that took place in a given year, placing their pin in the correct hole, and keeping track of their score. Twain suggested that players “play by the clock,” agreeing on the length of the game before beginning.

In his instructions, Twain wrote that the game was one of “suggestion.”

Whenever either player pins a fact, it will be pretty sure to suggest one to the adversary. The accidental mention of Waterloo will turn loose an inundation of French history. The mention of any very conspicuous event in the history of any nation will bring before the vision of the adversaries the minor features of the historical landscape that stretches away from it.

Twain weighted the importance of successfully remembered facts differently: Correct dates of the accession of monarchs and the beginning of presidential terms were worth 10 points, dates of battles were worth five, and everything else (“births, deaths, dates of inventions, and any other facts, great or small, that are datable and worth remembering”) would earn players one point.

The accompanying booklet contained dates of some historical events (here are the facts that were included in the booklet). But players weren’t confined to the information in the key. The game must have led to many a family squabble, with players insisting on the truth of uncertain and unverifiable “facts.”

Perhaps this factor contributed to the Memory Builder’s lack of commercial success. Twain sent a few prototypes to toy stores in 1891, but there wasn’t very much interest, so the game never went into production.

The University of Oregon’s library has put together an interactive version of the Memory Builder game, which you can play here. Click on the images below to reach zoomable versions, or visit the game’s page in the virtual library of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.