The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

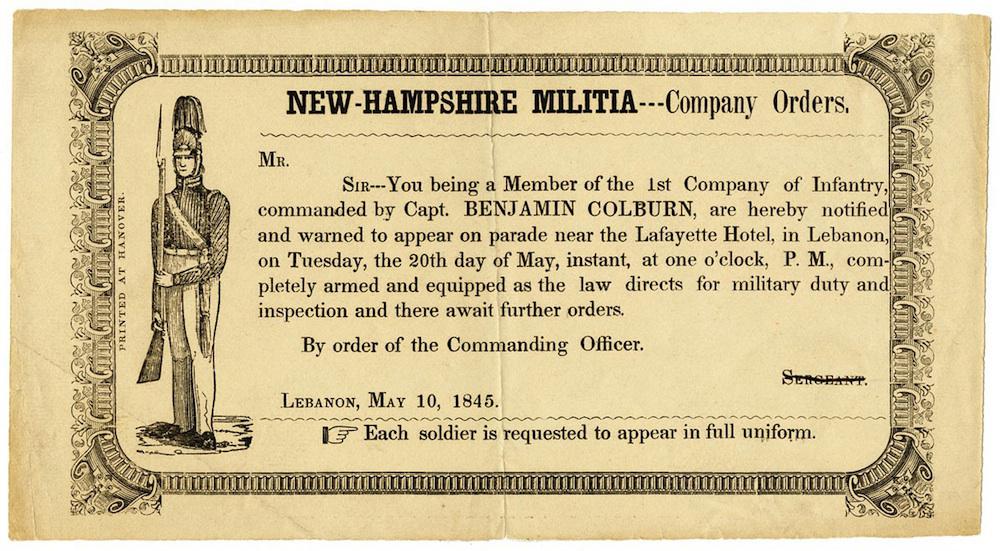

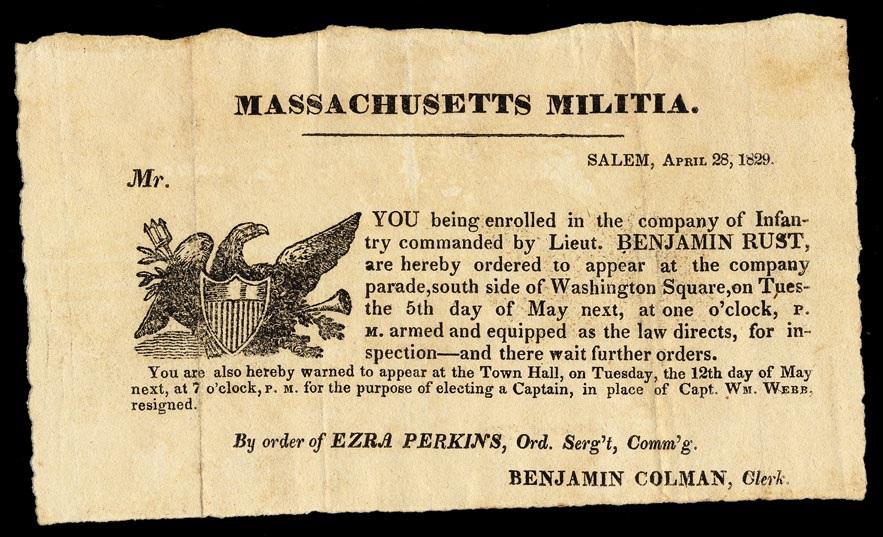

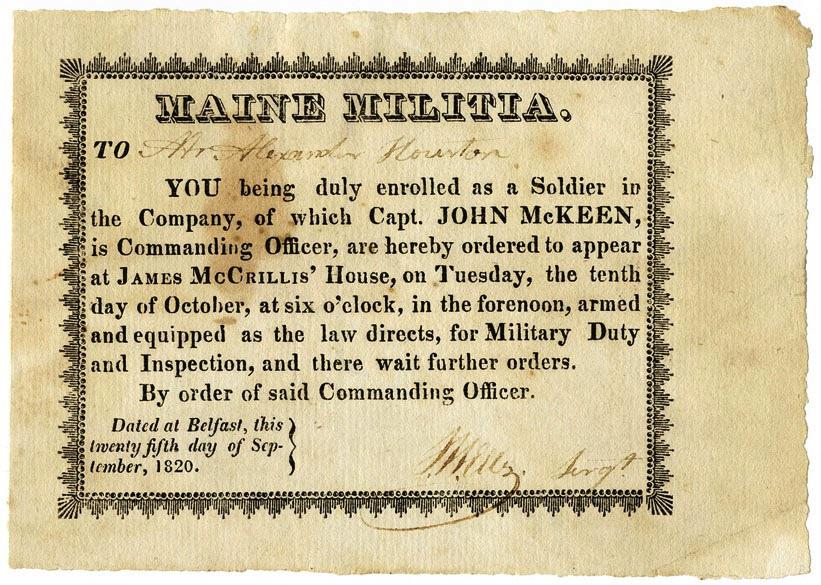

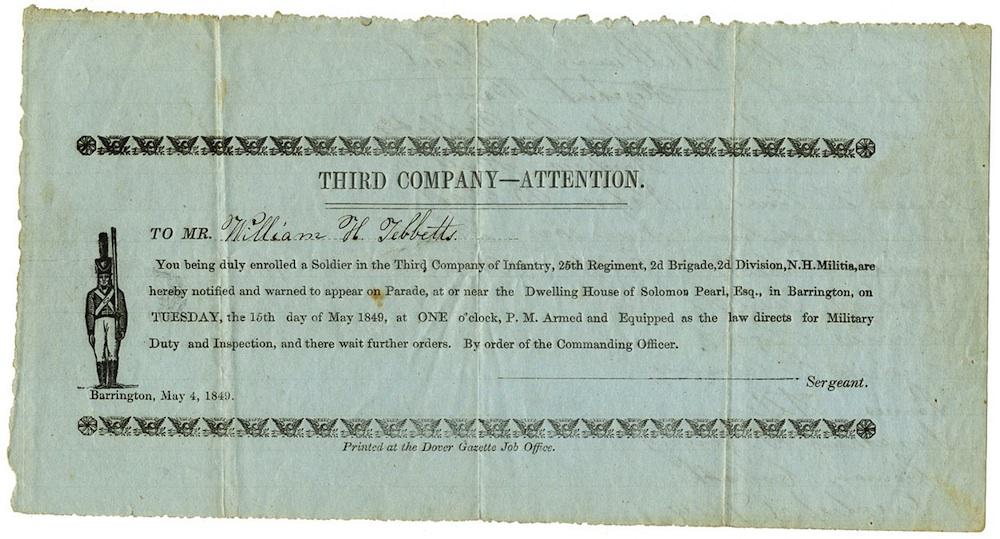

These muster notices were sent to eligible citizens in New England towns, calling them to come parade with their militia on an appointed day. Delivered on partial sheets of paper, and printed using the 19th-century equivalent of clip art (standard images of soldiers and eagles), the notices warned enrolled men of the need to bring the arms and equipment required by the state.

While the muster notices make the militias of the early Republic seem organized, reports of the situation on the ground differ. During the Revolutionary War, militia companies played their part alongside the Continental Army. The major law that regulated the tradition in the postwar era, The Militia Act of 1792, required that male citizens between the ages of 18 and 45 enroll in a militia—a locally administered force that the President should be authorized to raise when necessary. (In 1794, Washington used a force of 13,000 militia members to intimidate the Whiskey Rebellion out of existence.)

The law was not often obeyed to the letter. “Americans saw little reason to waste time on militia training when no danger threatened,” historian Barry M. Stentiford writes. “Musters, when held, became objects of ridicule,” bringing a carnival atmosphere to the towns that hosted them. The leaders of local companies would provide those who showed up with refreshments, enhancing the party scene. Many enrolled militia members who received notices like these would simply pay the small fine in order to get out of the obligation to show up.

Courtesy of Sheaff Ephemera.

Courtesy of Sheaff Ephemera.

Courtesy of Sheaff Ephemera.

Courtesy of Sheaff Ephemera.