The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

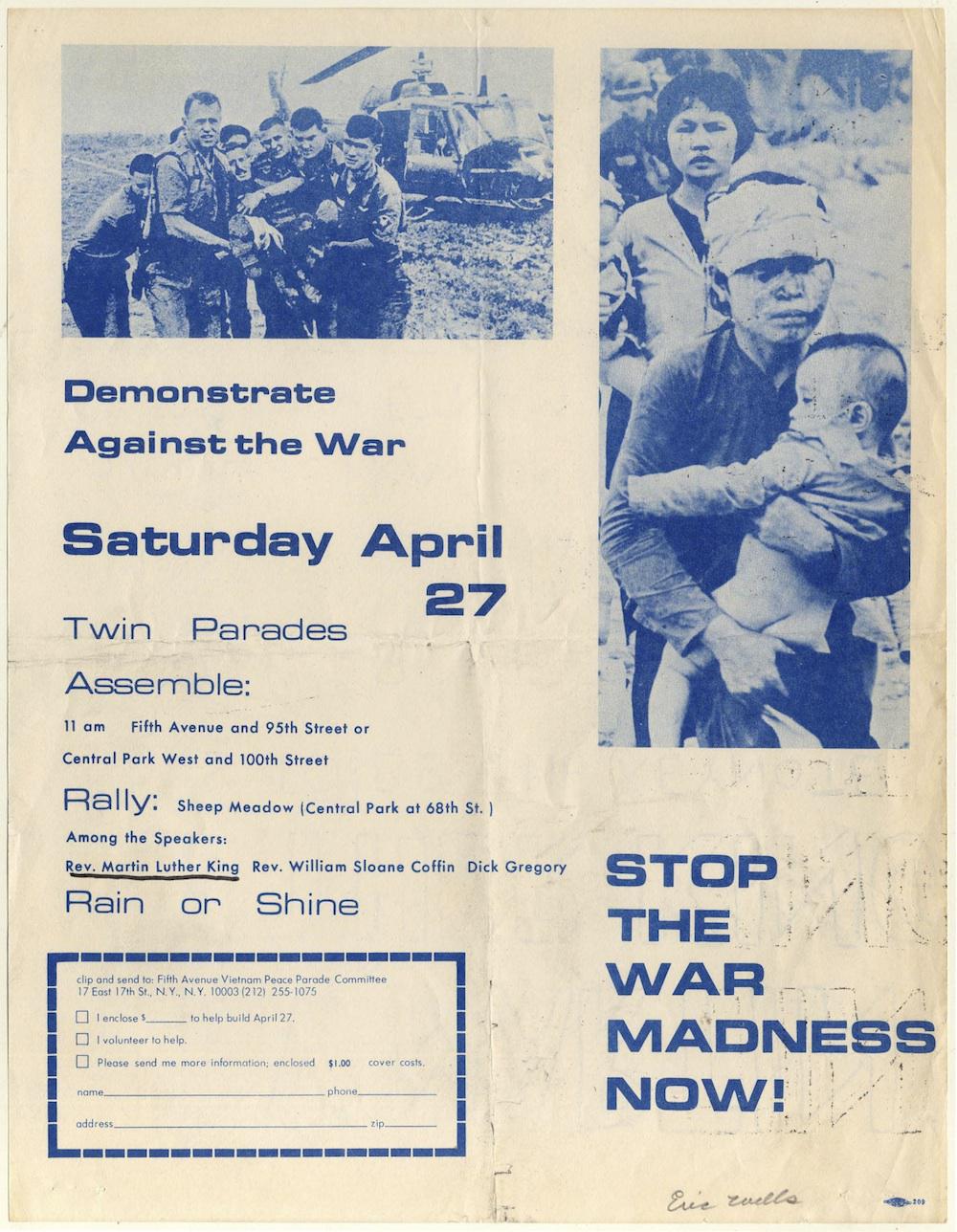

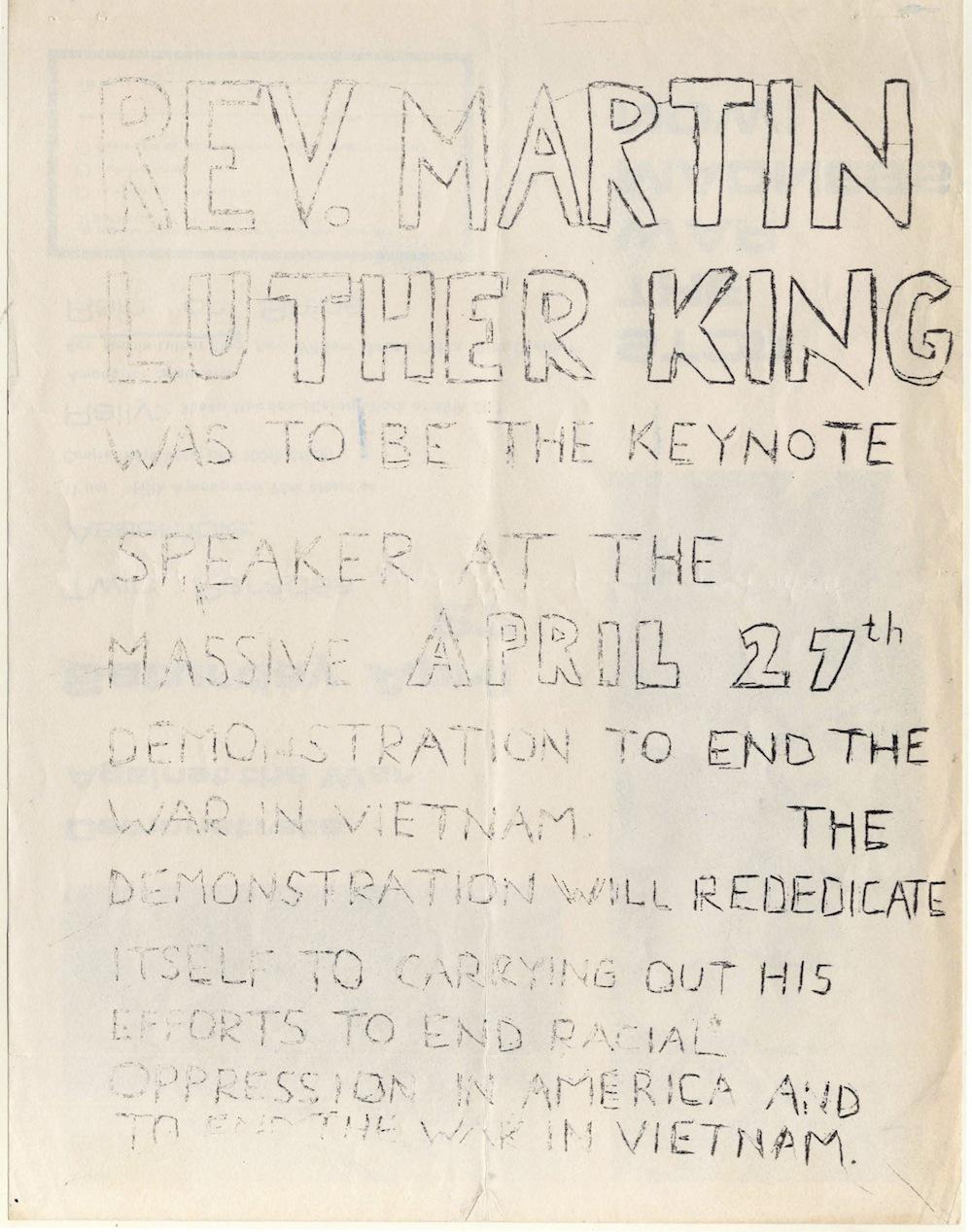

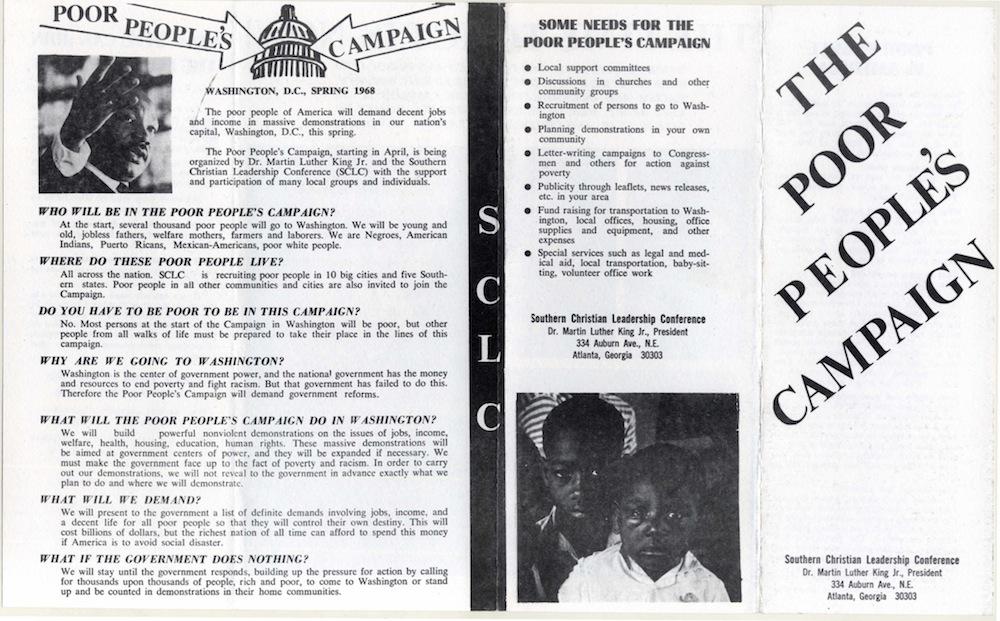

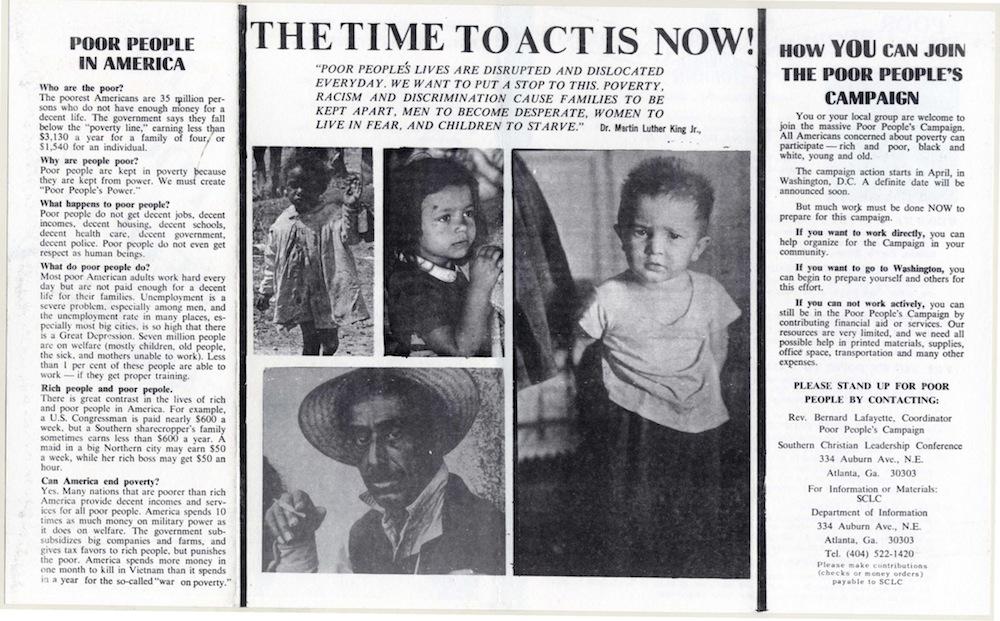

These flyers call people to join Martin Luther King’s last campaigns, against poverty and the Vietnam War. Two of them have been modified to act as commemorations of the leader’s assassination. These objects of movement ephemera are part of Tulane University’s Amistad Research Center’s “Print Culture of the Civil Rights Movement, 1950-1980” digital collection.

King gave the speech “Beyond Vietnam” a year before he was killed, on April 4, 1967; it was his first public antiwar speech. In it, he told listeners that he thought of the Nobel Peace Prize he received in 1964* as “a burden of responsibility,” “a commission to work harder than I had ever worked before for the brotherhood of man.” King perceived this burden and commission as international, not simply American; for that reason, he said, he had decided to speak on behalf of the people of Vietnam.

Since it denounced the effects of American intervention in Vietnam in the strongest of terms (“madness,” “poison”), King’s speech earned him censure in the public sphere, and chilled his relationship with Lyndon Johnson. Nonetheless, in the year between the speech and his death, King committed to the antiwar movement. As the first flyer below shows, he was signed up to co-lead a big peace rally in New York City three weeks after his assassination.

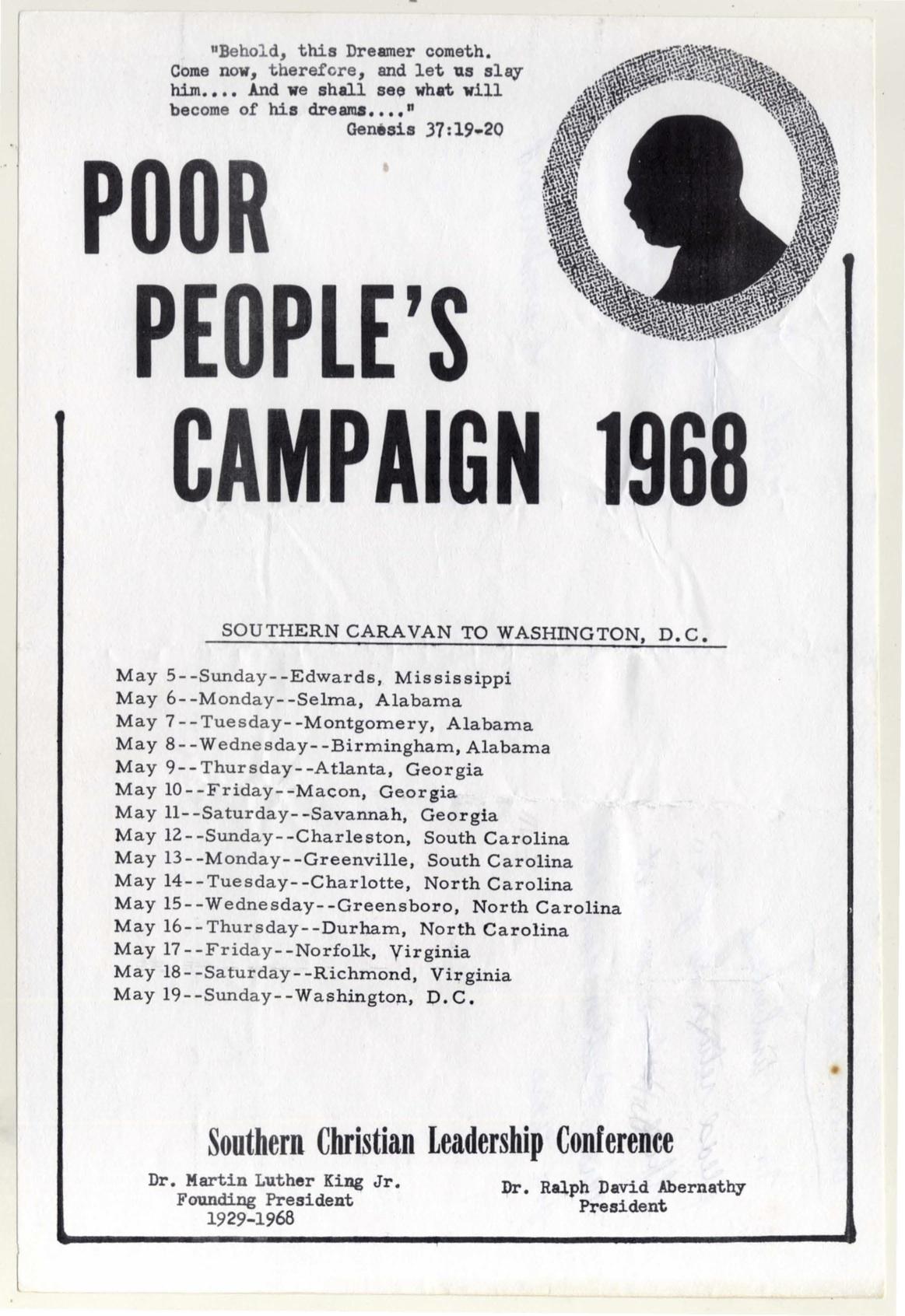

The other two flyers below call people to commit to the Poor People’s Campaign, which King announced in November 1967. The first flyer contains a full explanation of the goals of that ambitious campaign for economic justice. The second uses King’s silhouette to call mourners to come to the Capitol to carry out his goals.

Eric Steele Wells Papers, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Eric Steele Wells Papers, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Fannie Lou Hamer Papers, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Fannie Lou Hamer Papers, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Fannie Lou Hamer Papers, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

*Correction, Jan. 20, 2015: The original version of this post misstated the year that Martin Luther King, Jr. won a Nobel Peace Prize. It was in 1964, not 1954.