The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

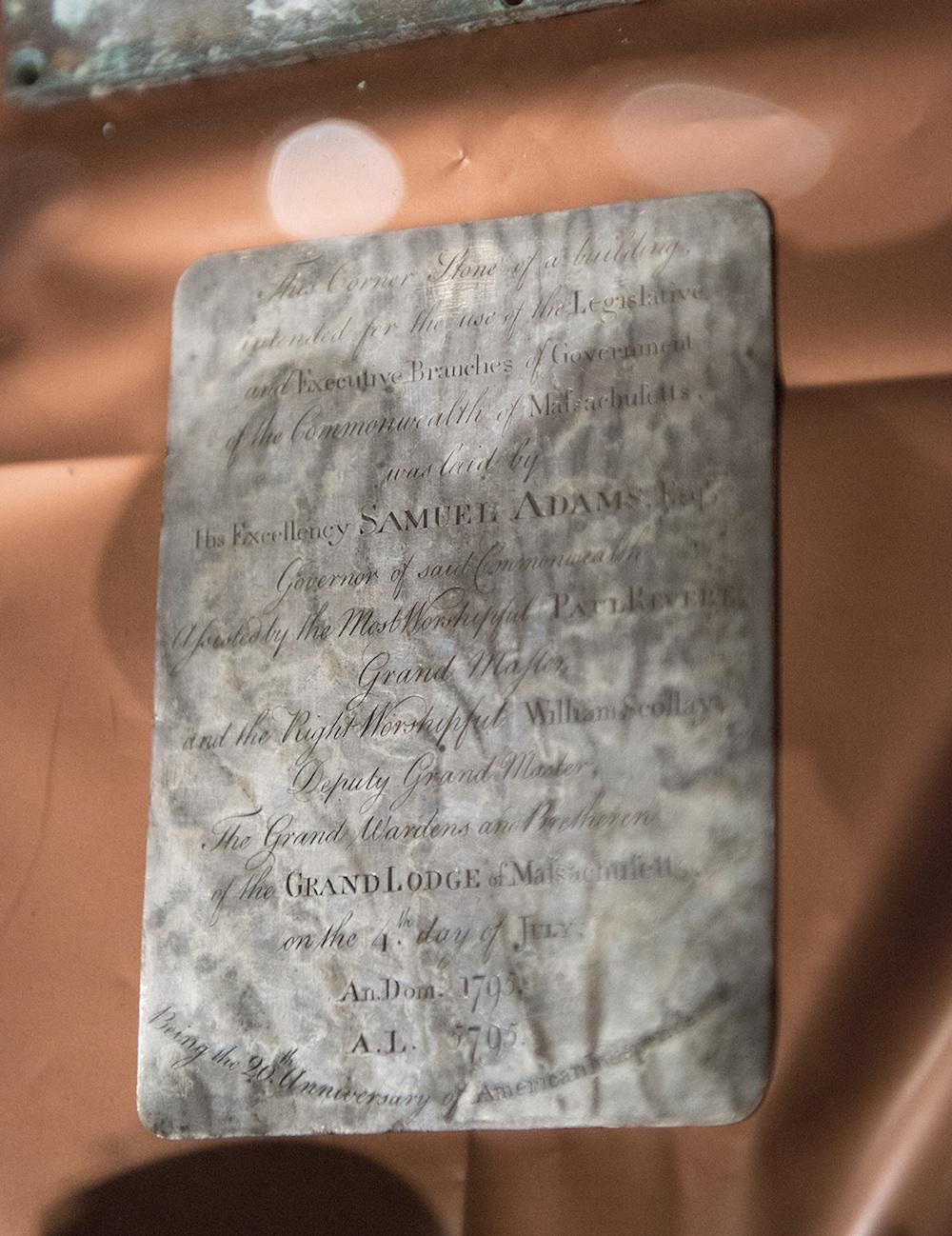

Tuesday night, at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, conservators opened a box that was buried beneath the cornerstone of the Massachusetts State House in 1795. Samuel Adams, then governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, installed the box with the help of Paul Revere, then the Grand Master of the Freemasons of Massachusetts. The deposit contained two layers of historical material: one from 1795, and another from 1855, when the little repository was opened and cataloged, then reassembled and augmented with new material from that time.

In Time online, Lily Rothman argues that the term “time capsule” is an inappropriate descriptor for this box, since the dignitaries who laid it under the cornerstone never specified an end date upon which the box should be dug up. Rothman points to the work of historian William E. Jarvis, who writes in his history of time capsules that the practice of putting sanctifying objects in the foundations of buildings, which dates back to ancient Mesopotamia, should be considered something different from a time capsule—less an archival message to the future, more of a blessing.

Jarvis argues that the Century Safe, assembled for the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, should be considered the first bona fide time capsule. The name “Time Capsule” was first used in 1939 at the New York World’s Fair. The idea of sending artifacts forward into the future gained popularity in the first half of the 20th century, when many world’s fairs and expositions featured a ceremonial capsule burial.

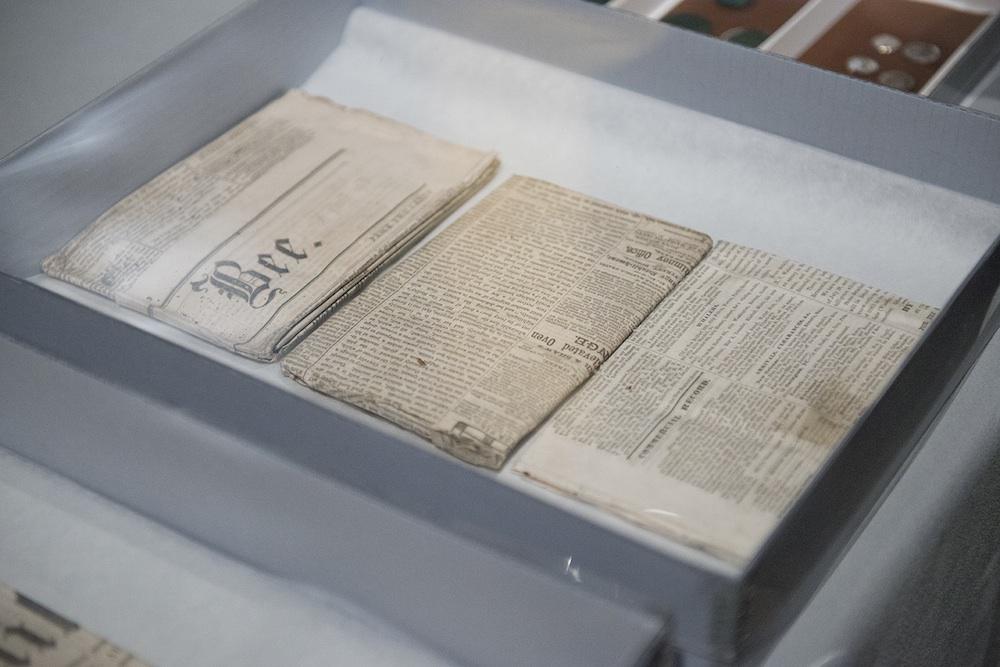

The Boston box turned out to contain an assemblage of commemorative items: a plaque describing the circumstances of the original laying of the cornerstone; 23 coins, with the oldest dating to the middle of the 17th century; a medal decorated with the head of George Washington; and five newspapers, excavated in delicate condition and still folded up to fit the box’s dimensions. The Boston Globe’s David Scharfenberg reported that the preservationists and state officials were still deciding how much to interfere with the box’s contents—a decision that will determine whether the newspapers can be unfolded, and the significance of their inclusion more fully understood.

One of the coins in the box, a Pine Tree Shilling, was minted in 1652 for the use of Massachusetts’ colonists, without the knowledge of the British monarchy.* Writing about the shilling, historian Mark Peterson tells the story of the colonists’ monetary defiance, which initially went unpunished during the kingless time of Oliver Cromwell. With the Restoration in 1660, Peterson writes, Charles II “demanded a reckoning of the colony’s conduct.” In a “dexterous act of verbal tribute,” the colony’s representative convinced the king that the pine was, instead, a royal oak, “the emblem of the oak which preserved his majesty’s life.” For the moment, Peterson adds, “the bluff succeeded.” Revere and Adams may have chosen to include the shilling as a token of the colony’s early independence.

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

*Correction, Jan. 7, 2014, 3:38 p.m.: This post originally misstated that the pine tree shilling was “printed.” It was, in fact, “minted.”