The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

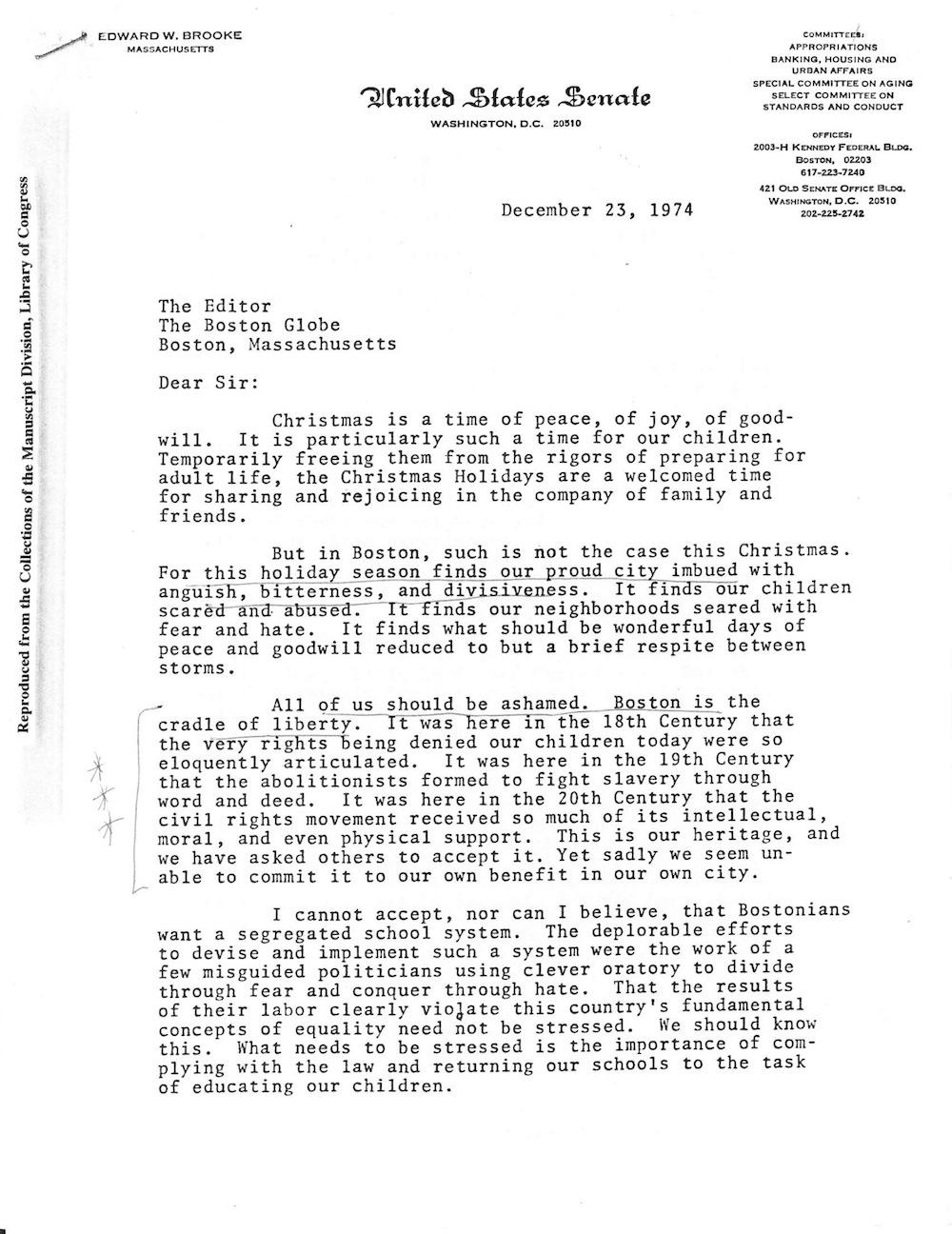

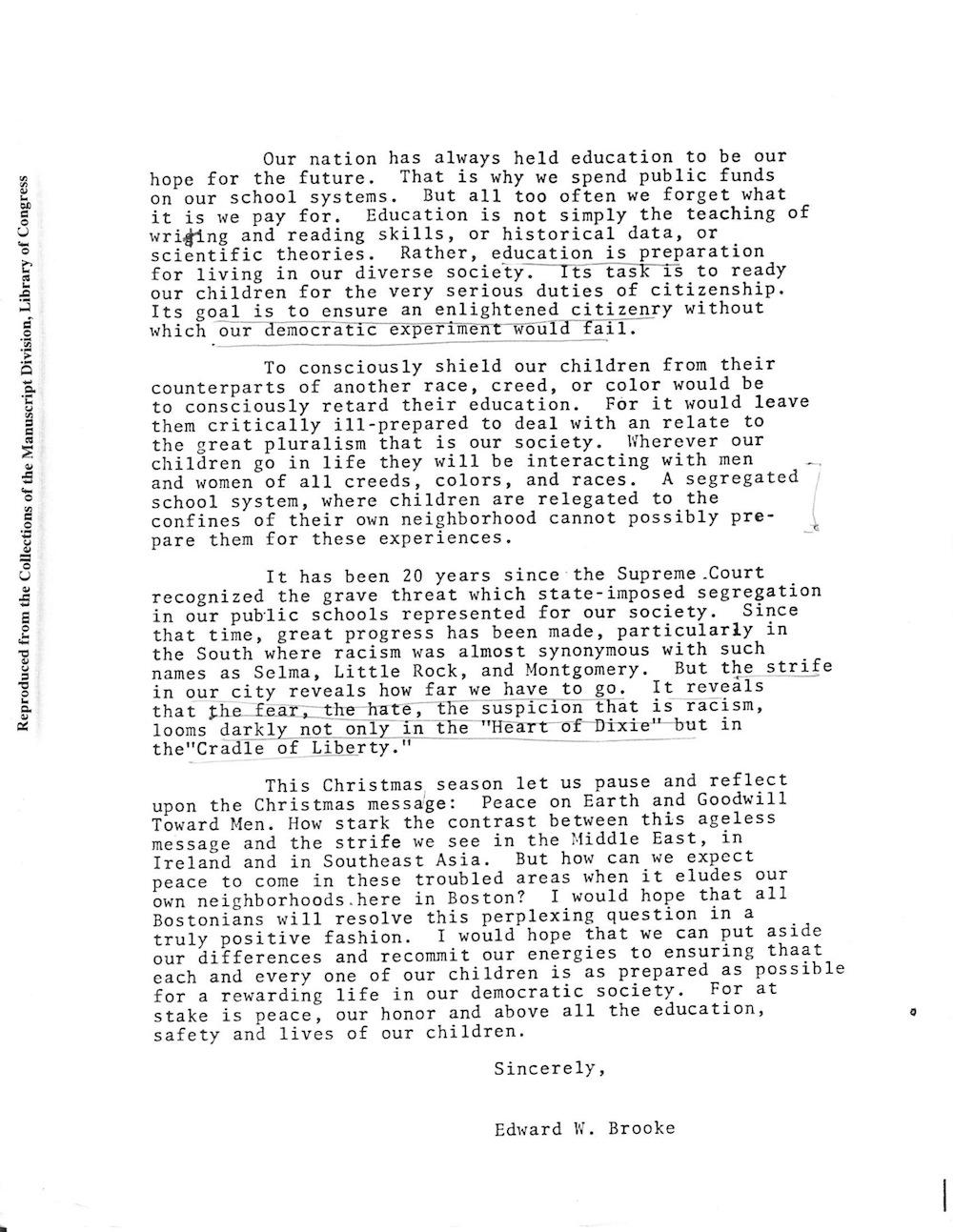

Published in the Boston Herald-American on Dec. 25, 1974 and in the Boston Globe on Dec. 26, this open Christmas letter from Massachusetts Sen. Edward Brooke asked a city divided over school busing to remember its tolerant heritage, and to reach deep to recover an empathetic spirit of cooperation. The letter came after months of bitter strife over school integration in the city.

In his book All Eyes Are Upon Us: Race and Politics from Boston to Brooklyn, historian Jason Sokol writes that Brooke’s early-1970s pro-busing crusade was an unlikely cause for the legislator, a moderate Republican and the first African-American to be elected to the Senate by popular vote. Brooke, who began his term in 1967, backed the Nixon-Agnew ticket in 1968, and was less popular among Massachusetts’ black residents than among its white majority in the late 1960s.

But by the time Brooke wrote this letter, he had successfully fought against two Nixon Supreme Court nominees who had records of opposition to civil rights causes. He became a diehard champion of school integration, and a sometimes-reluctant defender of the busing policies, upheld by the Supreme Court in 1971, that would make that integration possible.

Brooke wrote this letter at the end of an awful year for racial relations in Boston. Boston anti-busing movements gathered steam in 1974, and in April 1974, 20,000 anti-busing activists rallied on Boston Common. In May, Gov. Frank Sargent, who had long refused efforts to weaken the law, authorized a repeal of the state’s 1965 Racial Imbalance Act, making school integration voluntary. Then, in June, a district court judge, responding to a class-action suit brought by the NAACP, ruled that Boston must begin busing in the fall. The resulting demonstrations and racial violence rocked the city.

Sokol points out that Brooke wasn’t necessarily for busing, an unpopular tactic that, the Senator said in an interview with the author in 2009, “was an inconvenience to the parents, and an inconvenience to children.” But he was a strong enough advocate for desegregation of the schools that he found himself at the forefront of defenders of busing policies, which came under recurrent attack in Congress during the 1970s.

Library of Congress. Courtesy of Senator Edward Brooke.

Library of Congress. Courtesy of Senator Edward Brooke.