The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

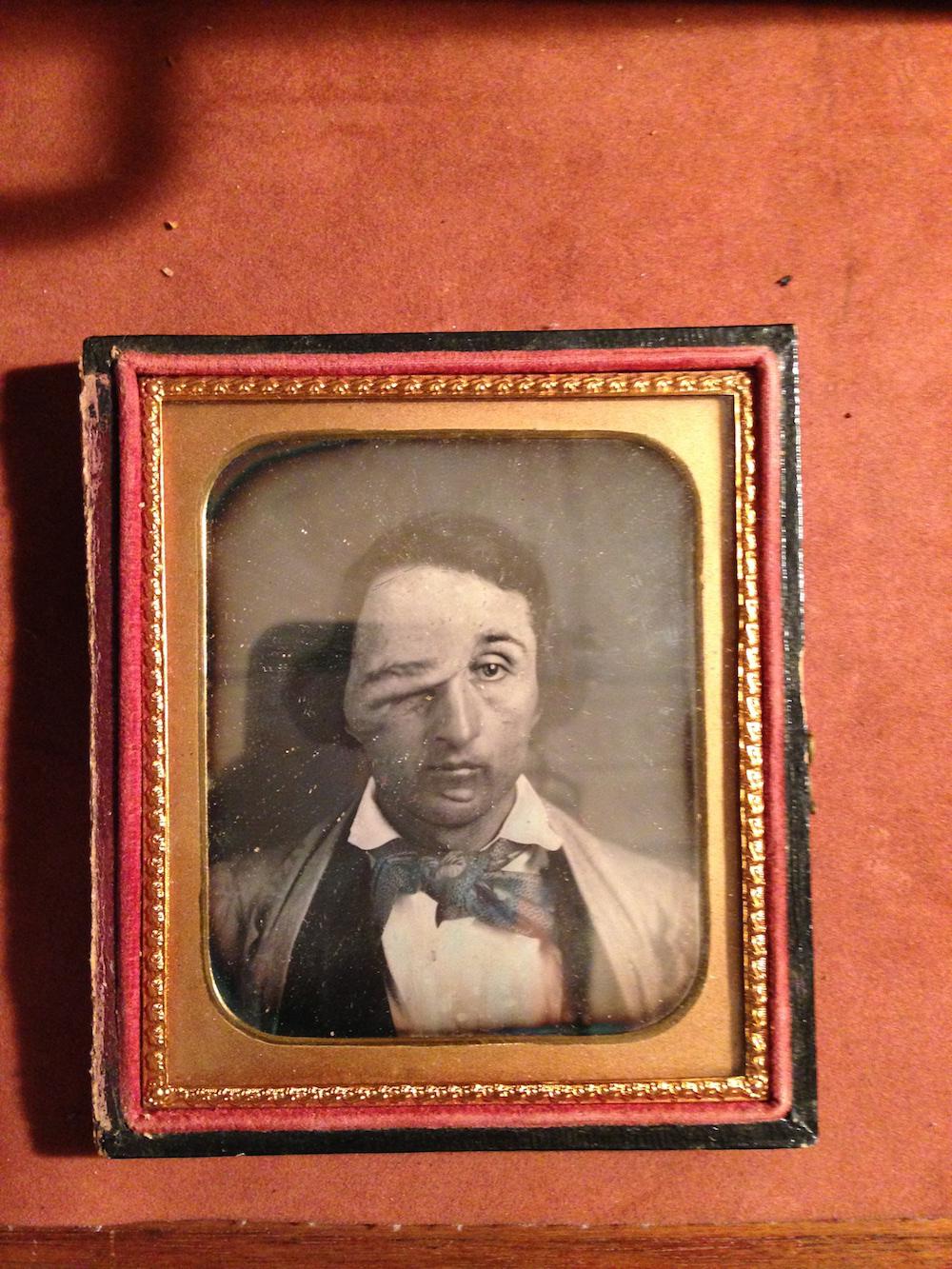

During the 19th century, physicians used photographs as consultation tools and treated patient photographs as prized collectable objects. Southern physician Edward Archelaus Flewellen sent this daguerreotype of A.P Jackson—one of the earliest surviving consultation photographs—to the famed surgeon Valentine Mott in 1856. Flewellen had been Mott’s student in New York, but returned to practice medicine in Thomaston, Ga. The patient, who was photographed by a local daguerreotypist, was a 33-year-old mechanic who developed a tumor (what Flewellen diagnosed as a case of “subcutaneous aneurism by anastomosis”) over his right eye when he was very young.

In a letter to Mott, Flewellen described the case in great detail, saying that he watched the tumor grow for the past five years. Flewellen asked Mott what surgical treatment he would recommend to “rid this poor young man of this hideous deformity,” and promised to send Mott another daguerreotype of Jackson (if the surgery was successful) so Mott could contrast the before and after photographs.

This exchange was remarkable because of its early date and the dramatic nature of the affliction, but not abnormal. Physicians regularly exchanged and collected photographs of their patients during the 19th century. The Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health at the New York Academy of Medicine, where this photograph is held, contains more than a few examples of early photographs used by physicians for consultation and comparison. Doctors treated photographs and other objects as specimens that could be used for a personal, and sometimes public, collection. Mott himself had a large public museum composed of pathological specimens and photographs from surgical operations.

There is no further record of Mott replying to Flewellen, so we do not know the fate of A.P. Jackson.

For more on the ethics of digitizing and sharing historical medical images, try today’s piece in Slate’s History section, by Vault blogger Rebecca Onion.

Image by Heidi Knoblauch.