The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

In September of 1914, as the armies of Europe were engaged in the Race to the Sea and the stalemate of the trenches loomed, Rudyard Kipling, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and other British authors collaborated on a remarkable piece of war propaganda.

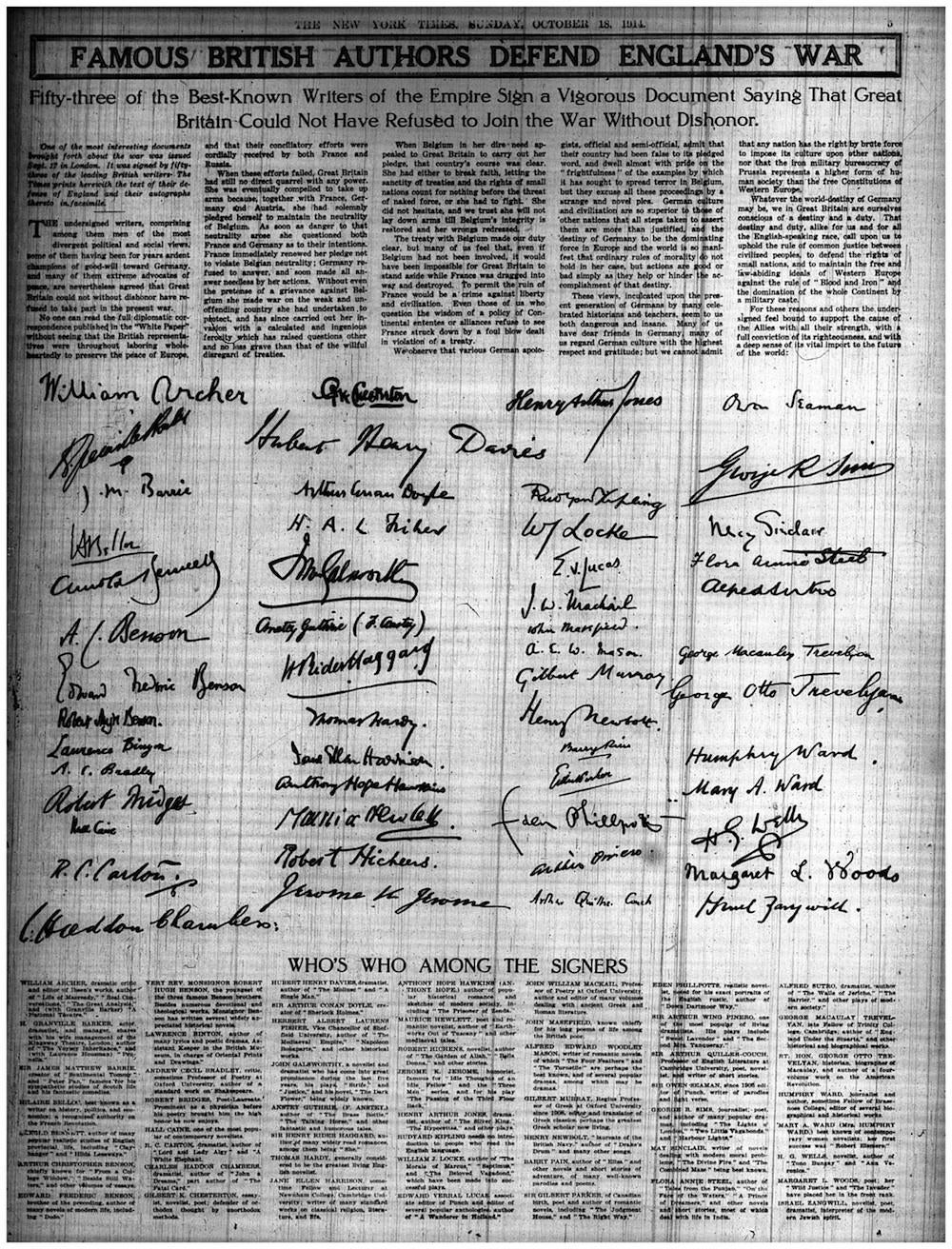

Fifty-three of the leading authors in Britain—a number that included Thomas Hardy and H.G. Wells—appended their names to the “Authors’ Declaration.” This manifesto declared that the German invasion of Belgium had been a brutal crime, and that Britain “could not without dishonour have refused to take part in the present war.”

The new War Propaganda Bureau had approached these authors earlier that month in a bid to secure the power of their pens—and the weight of their reputations—for the promotion of the empire’s cause throughout the world. The declaration provides a fascinating view of the period’s literary landscape; many of the authors listed are virtually unknown today, and some who remain popular are touted in the declaration for reasons that may now seem surprising. H.G. Wells, for example, is hailed not as the author of The Time Machine (1895) or The War of the Worlds (1898), but rather of Tono Bungay (1909) and Ann Veronica (1909).

Not to be outdone, German authorities responded to the declaration by bringing together an even larger assortment of artists, authors, and scientists to sign the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three, an astounding document which denied any German wrongdoing in Belgium and bewilderingly accused the Allies of “inciting Mongolians and negroes against the white race.”

Many of the signatories of the British Authors’ Declaration grew ambivalent toward their involvement with the War Propaganda Bureau. H.G. Wells satirized his own wartime career in Mr. Britling Sees It Through (1916), and by 1918 had withdrawn from propaganda work altogether; Ford Madox Hueffer (later Ford) went even further, laying down his pen in 1915 to instead enlist as an infantryman in the Welch Regiment—a set of experiences that would inspire his Parade’s End tetralogy (1924-1928). The unity of vision and purpose the declaration so strongly implied did not endure.

A longer version of this post appeared on Oxford University’s World War One Centenary Blog, Continuations and Beginnings.

Click on the image to reach a zoomable version.

New York Times, October 18, 1914, p SM5.