The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

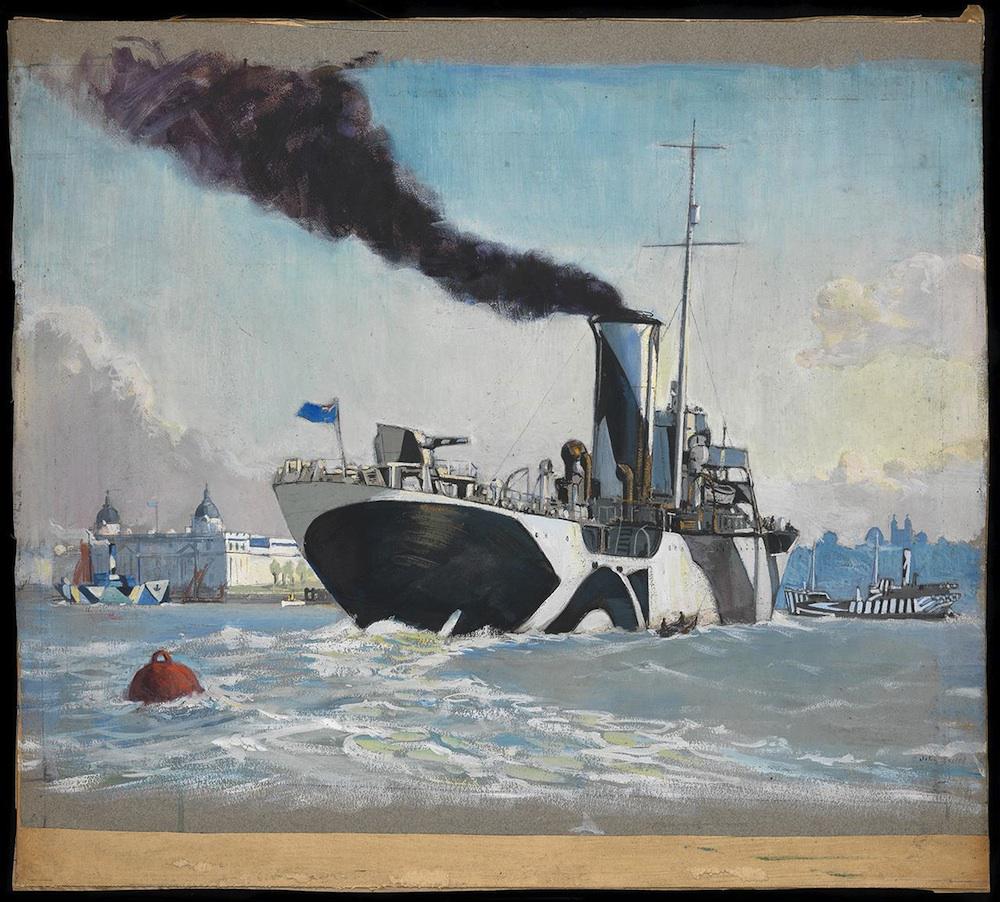

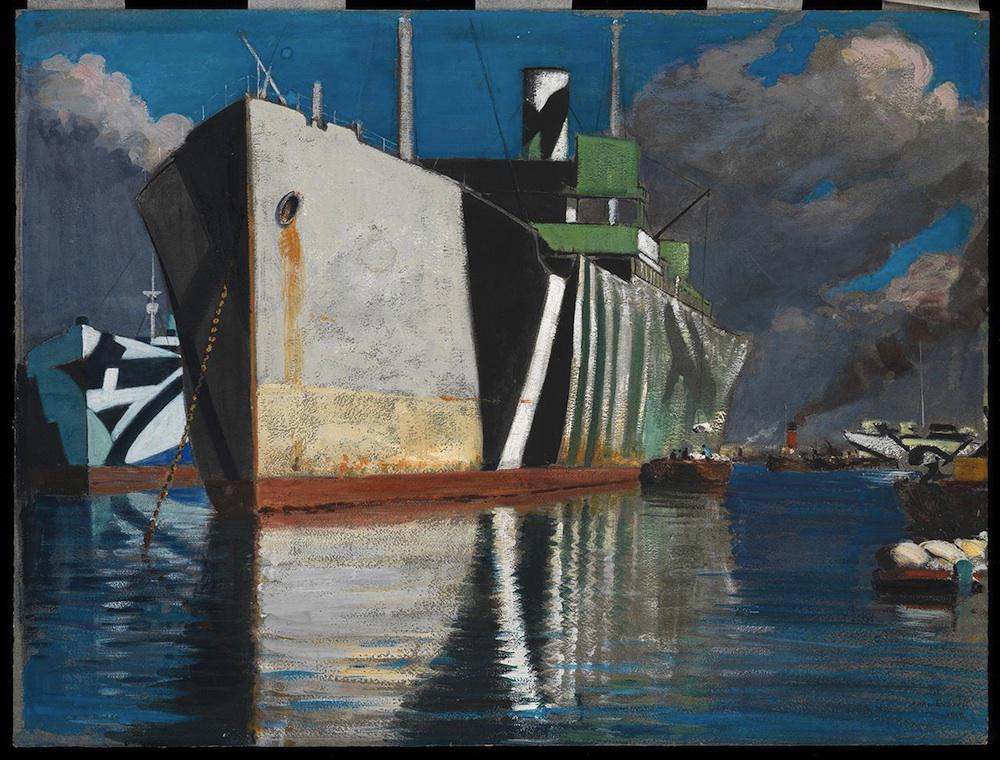

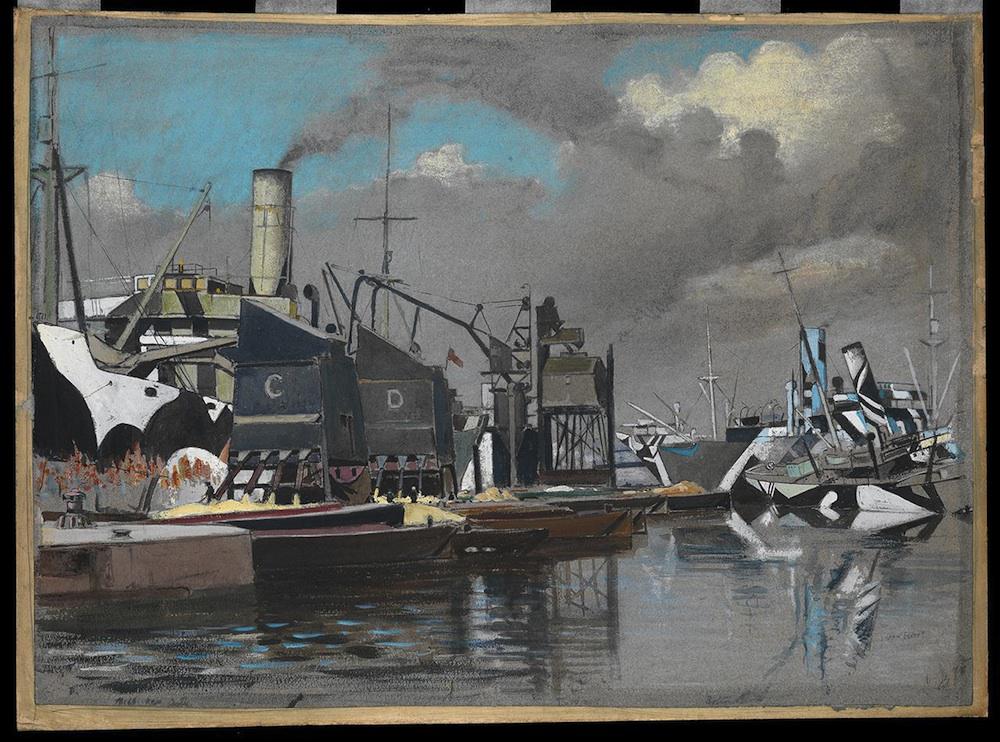

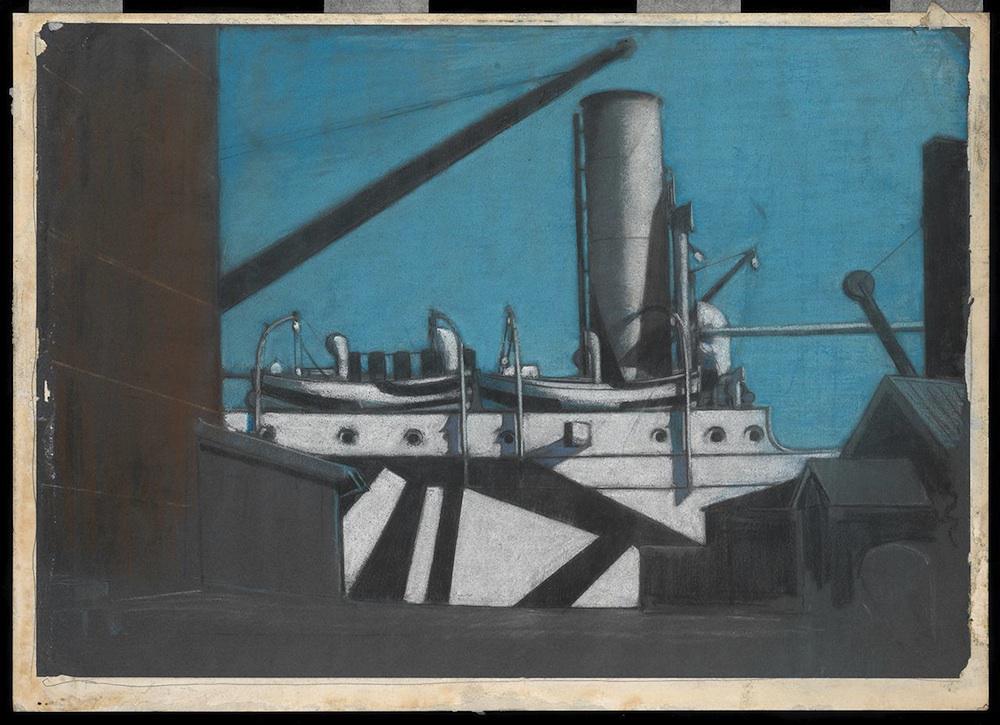

In 1918, maritime painter John Everett received special permission from the British Ministry of Information to represent river scenes in London. Everett became fascinated by dazzle-painted ships, and made many images of the vessels.

Dazzle painting, in which ships were decorated with unpredictably zigzagging stripes, was the brainchild of British artist Norman Wilkinson, who developed the idea in response to the toll that German submarines were exacting on the British fleet. The result of the strategy is wild-looking vessels that look like they belong in Cubist or Vorticist paintings. (io9 has a good roundup of photographs of these ships, here.)

How, exactly, could this weird idea have worked? The blog Camoupedia has reprinted the text of an article about dazzle camouflage and John Everett’s paintings that originally ran in the British magazine Land & Water in February 1919. The author, Haldane Macfall, who was an officer in the military as well as an art critic and writer, gives multiple counterexamples of solid-colored objects that made historically good targets on the field of battle.

“It may be stated almost as a law that a solid color comes nearest to the most deadly target—a dark silhouette,” Macfall wrote. “As a grim old musketry sergeant used to put it, [a solid object] is ‘more restful to the shooter’s eye.’ ”

Macfall also quoted Jan Gordon, a Royal Navy lieutenant who had collaborated with Wilkinson in the development of the camouflage strategy. Gordon explained: “Dazzle-painting attains its object, not by eluding the submarine by invisibility, but by confusing his judgment.”

The Everett images, which situate the ships in their context, show how this might be possible. The ships are strangely difficult to look at, almost fading into their backgrounds, despite their gaudy coats of paint.

While the British Admiralty claimed that WWI-era dazzle-painting had been effective, David L. Williams writes in his history of naval camouflage during the first and second World Wars that this has to be considered a subjective opinion, based on a small sample size. By World War II, the technique was modified and then abandoned, as targeting systems improved and ships faced threats from the air.

These John Everett drawings are on view at the National Maritime Museum in London as part of the exhibit “War Artists at Sea,” through February 2015.

© National Maritime Museum, London.

© National Maritime Museum, London.

© National Maritime Museum, London.

© National Maritime Museum, London.

© National Maritime Museum, London.

© National Maritime Museum, London.