The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

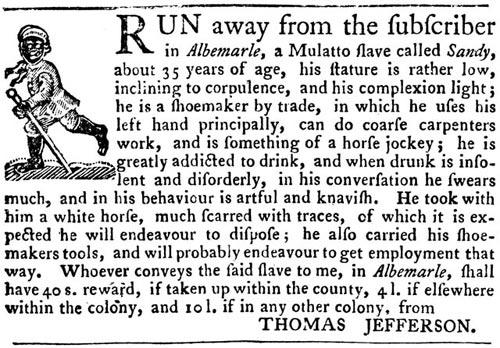

Seven years before writing that “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson ran this ad in the Virginia Gazette, offering a reward for his runaway slave, Sandy. He describes Sandy as “artful and knavish” and “greatly addicted to drink”. At the time, Jefferson possessed upwards of 50 slaves, inherited from his father, although he would come to own hundreds over the course of his lifetime. Jefferson eventually reclaimed Sandy, who he sold for 100 pounds several years later—a common fate of slaves deemed “troublesome”.

Jefferson’s views on slavery were complicated, to put it mildly. On the one hand, he made several prominent stands for antislavery causes over the course of his lifetime, especially during his early career. In 1784, for instance, Jefferson put forward a provision that sought to prohibit slavery in all new states carved from the territories. This amendment to that year’s Ordinance would have effectively blocked the westward expansion of slavery. It failed to pass by a single vote.

Yet Jefferson also frequently acted in the interests of his planter class. The same year that he printed this ad, Jefferson scuttled a manumission law in Virginia that would have enabled slaveholders to more easily free their human property. He repeatedly insisted that black and white could never peaceably live together, and in fact, that racial warfare was all but inevitable. Yet most historians now agree, as Annette Gordon Reed has long maintained, that Jefferson fathered several children with his slave, Sally Hemings. Aside from a handful of slaves (including some of Sally Hemings’s children), Jefferson never freed his bondspeople—unlike George Washington, who left provisions in his will for the emancipation of his slaves upon Martha’s death.*

*Correction, Oct. 1, 2014: This post originally misstated that every enslaved person on Washington’s plantation was manumitted upon his death. Washington left instructions that the slaves he owned be emancipated upon his wife’s death. Oher people enslaved at Mt. Vernon were subject to different rules of ownership, and Washington could not have left directions as to their fates.