The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

Horace Poolaw, of the Kiowa tribe, took thousands of photos of his multitribal community around Anadarko, Oklahoma, between the 1920s and 1950s. A selection of his images appears in a new volume, For a Love of His People: The Photography of Horace Poolaw, which accompanies the National Museum of the American Indian’s exhibition of the same name. (A few more Poolaw photos can be seen on the NMAI’s website.)

While many non-Indian photographers of the American West in the 19th and early 20th centuries made images of Native Americans with a variety of goals in mind (commercial exploitation; anthropological preservation; artistic production), Native photographers also stepped behind the camera to document their own communities. Among them, Poolaw left behind an exceptionally complete archive, which represents 20th-century Native life in Oklahoma as a fluid mix of traditional and modern cultures.

“Poolaw kept his pictures close,” historian Martha Sandweiss writes in a preface to the volume. He tended to produce images for their subjects only, selling some souvenir copies at fairs and gatherings, but not to “government publications or illustrated magazines.” As a result, the images feel personal and intimate.

The scholars that worked on the exhibition unearthed many family stories to go along with the recovered negatives. They’re still trying to identify some of the people in the images; the NMAI would be happy to receive any relevant information.

© 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw.

Horace Poolaw’s eldest son Jerry Poolaw (Kiowa), Mountain View, Oklahoma, ca. 1929.

© 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw.

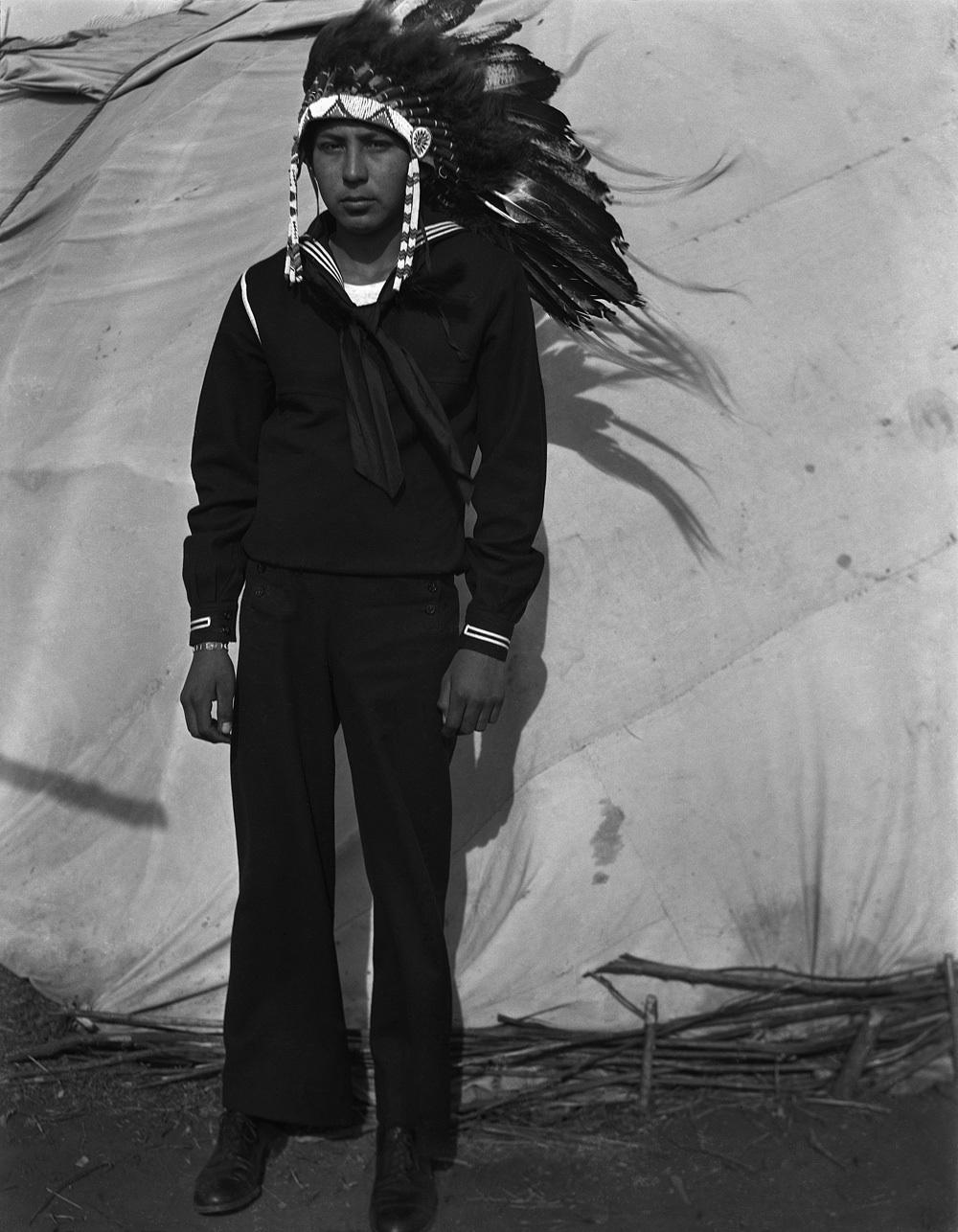

Jerry Poolaw (Kiowa), on leave from duty in the Navy, Anadarko, Okla., ca. 1944.

© 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw.

Horace Poolaw (Kiowa), aerial photographer, and Gus Palmer (Kiowa), side gunner, inside a B-17 Flying Fortress, Tampa, Fla., ca. 1944.

During World War II, Poolaw served three years in the U.S. Army Air Forces as an instructor in aerial photography. In this constructed image, photography professor Tom Jones writes, “Truth, humor, and stereotypes collide, as each man dons a jumpsuit and war bonnet for the camera, ready for warfare in the twentieth century.”

© 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw.

“Carp and catfish caught after a flood of the Washita River,” Mountain View, Oklahoma, ca. 1930. Unidentified men and boys, with the exception of Jasper Saunkeah (Kiowa), who stands second from left.

© 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw.

Sindy Libby Keahbone (Kiowa) and Hannah Keahbone (Kiowa), Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, ca. 1930.

Art historian Laura E. Smith, writing about women in Poolaw’s portraits, notes the similarity between Hannah Keahbone’s bob and the au courant Clara Bow style of the late 1920s. Smith quotes Vanessa Jennings, a Kiowa Apache/Gila River Pima historian and beadworker, who remembered Hannah Keahbone as “bold and beautiful,” a rebel who wore makeup and carried “a small metal flask held in place by the tight roll of her stockings, just above her knees.”

© 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw.

“Lucy ‘Princess Watahwaso’ Nicolar (Penobscot), far left, Bruce Poolaw (Kiowa) fourth from left, Justin Poolaw (Kiowa) far right, with friends at Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show, on their way to New York City, Pawnee, Oklahoma, ca. 1930.”

In an essay accompanying this photo, Horace Poolaw’s grandson John remembers loving the image at age 12, when he caught sight of it among a larger group of Poolaw photographs. “Until I saw this particular photo,” John Poolaw writes,

the only other [historical photos] I had seen of Indians were the occasional images in textbooks, which were most often boarding-school portraits in which the Indians always appeared to be sad and stiff. I enjoyed seeing my grandpa’s photo of sharply dressed Indians by a shiny car—they all looked so happy.

Later in life, Poolaw reflects, he realized that most of those modern-looking young people in the portrait “probably spoke their native Kiowa language and probably all still carried out traditional Kiowa customs.” “I found it even more fascinating,” he writes, “that they were able to do so and look so care-free, confident, and elegant in adapting to their changing worlds.”