The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

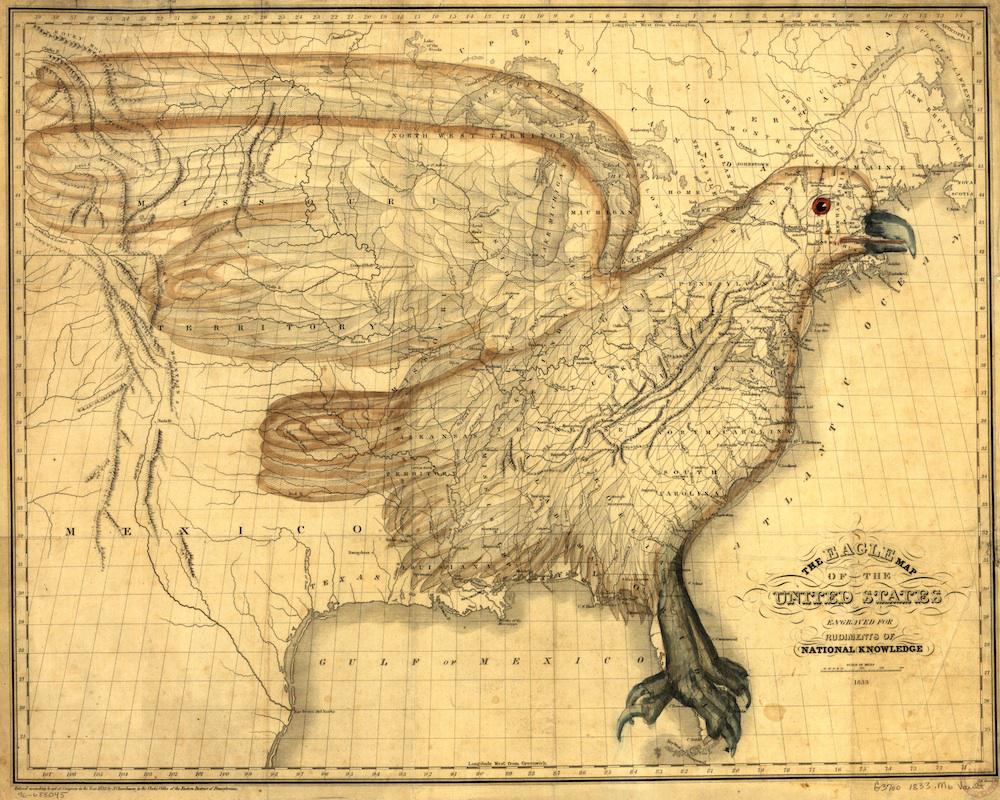

The “Eagle Map of the United States, Engraved for Rudiments of National Knowledge” first appeared in an 1833 atlas published by E.L. Carey and A. Hart of Philadelphia. At nearly 400 pages, the atlas, titled Rudiments of National Knowledge, Presented to the Youth of the United States, and to Enquiring Foreigners, was meant to fill a void in educational texts about American history and geography.

The idea to superimpose an eagle over a map of the United States came to mapmaker Joseph Churchman thanks to a coincidence of shadows and light that momentarily tricked his eye into seeing the bird on the page. Though he wrote in the atlas that he was initially “disposed to discard the idea, as merely a sportive play of the imagination,” he later decided to execute it.

Churchman had a pedagogical goal: he wanted to provide a study aid to help young students learn the borders of the states within their union. During the early 19th century, geography was gaining traction as a pedagogical tool. The study was seen as a way to foster a sense of national identity. Though the use of maps to teach geography seems intuitive now, it wasn’t until the 1820s that teachers began regularly using them in class. Churchman aimed to build upon this new culture of visual learning by layering a familiar image on top of the map to be memorized.

Churchman’s second motive was to promote unity and discourage secession. At a time when national unity was not a foregone conclusion, Churchman believed that a fear of being “blotted out from the eagle map of the United States” might discourage a state from choosing to “separate their interests from the interests of the Union.” And the eagle, an American emblem since it was chosen for the national seal in 1782, was a fitting figure for such a patriotic appeal.

It’s worth noting that the eagle was not a perfect fit for U.S. borders in 1833. For one thing, Churchman couldn’t seem to accommodate Maine. “The citizens of Maine, it is presumed, will not be offended at the impossibility of comprehending their department in the Union, within the regular form of the figure,” he wrote. He suggested that they might be appeased to instead consider themselves “the cap of liberty, attached to the eagle’s head.”

Although Churchman hoped the Eagle Map would aid future generations of geography students, it became obsolete soon after he conceived it. The boundaries encapsulated by the eagle’s tail feathers shifted in the years following the map’s publication, rendering it inaccurate. By 1845, Texas had been annexed to the United States, followed by a large swath of western land in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

Click on the map to reach a zoomable version, or visit the map’s page in the Library of Congress’ digital archives.

Library of Congress.