The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

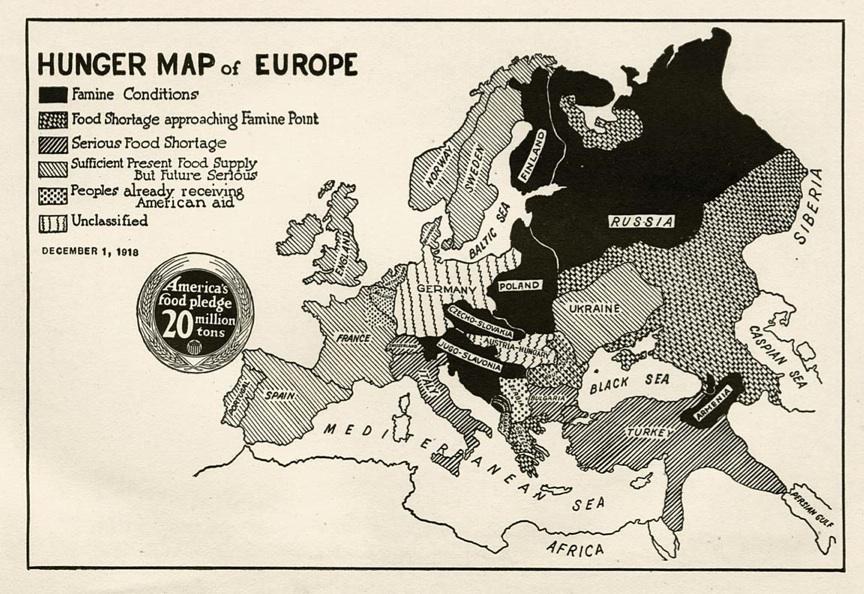

This map prefaced a 1918 book by the United States Food Administration, titled Food Saving and Sharing: Telling How the Older Children of America May Help Save From Famine Their Comrades In Allied Lands Across the Sea. “Remember,” the text asked its readers, “that every little country on the [map] is not merely an outline, but represents millions of people who are suffering from hunger.”

The book was printed after two years of food restriction within the United States. The United States Food Administration, formed after Woodrow Wilson’s passage of the Lever Act in 1917, had asked citizens to eat less meat and sugar, to plant gardens, and to eat everything on their plates. Children, particular targets of these efforts, joined voluntary programs like the School Garden Army, which at the time of the publication of this pamphlet had “more than 1,500,000 enlisted soldiers.”

The anonymous authors of this book looked to persuade children who might be relieved by the end of the war not to revert to their previous habits, arguing that much work was left to be done in Europe.

Children might be enticed to help the still-hungry Allies by reminders about the causes of the food shortages in European countries. German villainy, now history, could still serve as persuasive force when it came to enlisting children’s help in rebuilding.

“Everyone knows…how the German armies behaved after they had made their way into Belgium; how they murdered and tortured and looted and destroyed,” the authors wrote. “They were not unwilling that the Belgians should starve. The more that died the better; then the land would be free for them to occupy.” In France “the Germans set to work deliberately to do as much harm as possible,” destroying fruit trees and vineyards; they poisoned wells and burned houses.

The authors also tried a little bit of shame, asking readers to think of a more disciplined diet as a sign of national maturity. The United States, as a “young country,” was greedy, the authors wrote. But this mania for a groaning table was unbecoming to a nation that was coming into its own on the world stage.

“Even before the war,” the authors wrote, “people were beginning to find out that this fashion of living was foolish and extravagant, that preparing so many kinds of food in elaborate ways was a great waste of time and material and that an overloaded table was in poor taste.”

Thanks to Shirley Wajda, curator of history at the Michigan State University Museum, for suggesting this item.