The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

The great project Public Domain Review recently posted about these prints, which are held at the Library of Congress. The series, credited to the Japanese Department of Education, represents the trials and tribulations of Western inventors and intellectuals. While the Library of Congress places their publication in the late 19th century, the Public Domain Review found another set on the website of the University of Tsukuba Library that was dated more specifically, to 1873.

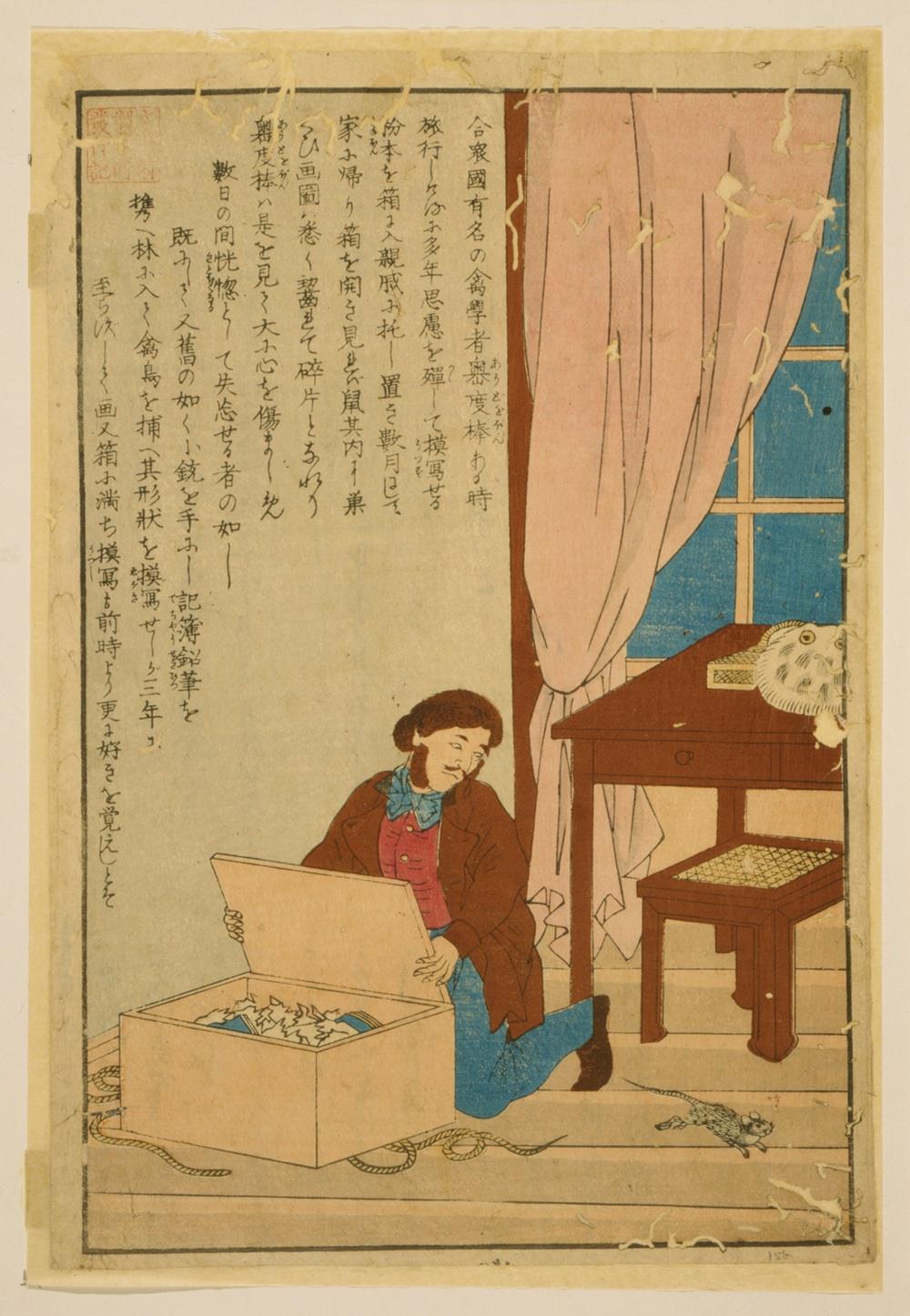

While I had seen scattered prints from this set before—the New-York Historical Society blogged about the unforgettable image “Audubon Opening His Box of Watercolors Destroyed by Norway Rats” last year—I had not realized that such a closely related group existed. The scenarios represent invention and writing as alienating, frustrating experiences, bound to annoy one’s family and try one’s mettle.

The prints reflect changes in a country that had been closed to foreign trade until 1853, when the United States forced Japan into trade treaties with Western nations. These changes brought Japan into direct contact with Western ways of manufacture for the first time.

Why show the problems inherent in innovation? Perhaps the approach was meant to paint perseverance in these fields as morally correct. The Public Domain Review suggests that “the illustrations might be hinting that the nation of Japan in particular has the qualities of patience, will-power, and tenacity to succeed in such fields.”

Last year I blogged about some Japanese woodblock prints from around the same period that advised people on new Western methods of fighting diseases like cholera and smallpox. It’s interesting to think of those images, which emerged from the ferment of Western ideas with Japanese beliefs, alongside this set of similar representations.

I’m including the Public Domain Review’s English glosses of the Japanese text below. The anonymous author of the PDR post thanked Ben Schlabs and Tomoko Tanaka for translation assistance, to which I must add my own gratitude.

Library of Congress.

“The American celebrity [John James] Audubon’s important travel documents that he had been copying and gave to relatives for safekeeping were eaten by mice. He was extremely sad but tried again, and after just three years, his boxes were once more full of paper.”

Library of Congress.

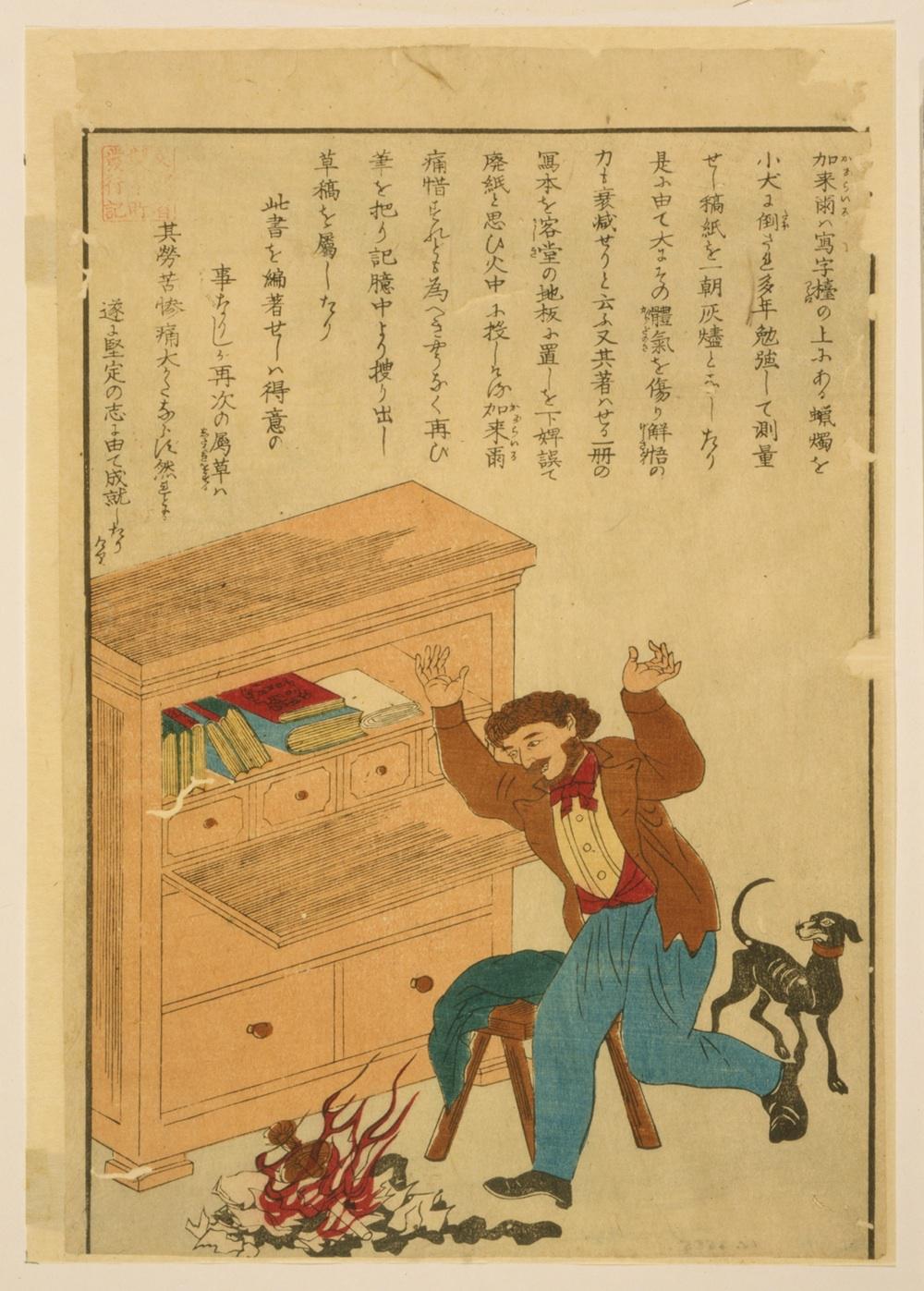

“A dog knocked over the lamp on the table which held [writer Thomas] Carlyle’s important papers on which he had worked for many years. His manuscript caught fire, turned to ash, and Carlyle became sick from depression (?). In the end, everything still turned out great.”

Library of Congress.

“The Englishman [Richard] Arkwright wanted to make a spinning-frame. It took him such a long time that he became very poor and so his wife got mad and broke his machine. Angry at her, he sent her away. But even after all this, he succeeded and became extremely rich.”

Library of Congress.

“The Englishman [James] Watt wanted to make a steam engine. He spent so much time on it that he upset his aunt. Finally, however, he was successful.” (The story of Watt and the teakettle, which is possibly apocryphal, has always been told as a childhood origin story: the relative observed the young Watt futzing with a steam kettle, and told him he should make himself useful instead. This image, for whatever reason, casts a slightly older Watt in the role.)

Library of Congress.

“The Frenchman [Bernard] Palissy wanted to make nice china. His wife and kids got very upset with him when he started throwing their furniture into the kiln (?) to feed it. But finally he succeeded.”

Library of Congress.

“The Englishman [John] Heathcoat wanted to make a lace-making machine. After trying so many times and failing he grew very poor. This made his wife very sad. Eventually, however, he succeeded and was able to give his wife lace.”