The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

Ever since seeing this amazing list, which was billed as “reasons for admission” to a 19th-century mental institution in West Virginia, I’ve been wondering about its meaning. It seemed too funny to be true. Did 19th-century doctors really commit patients because they read novels?

Bookseller John Ptak recently blogged about an 1848 Dorothea Dix pamphlet, which contains the two shorter, similar lists in this post. Dix, an activist and advocate for kinder treatment of the mentally ill, wrote this pamphlet as a memorial (a petition), asking Congress for a grant of land upon which to build asylums.

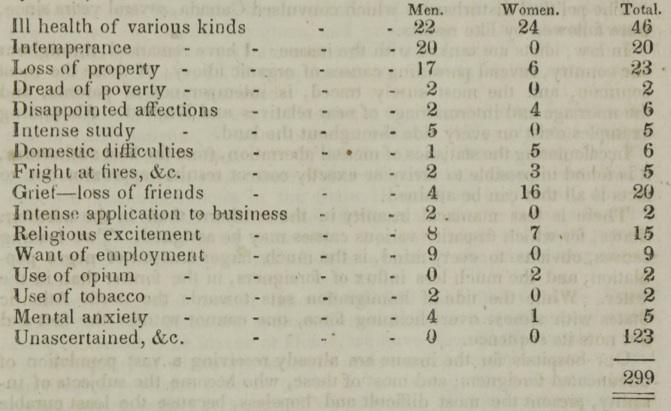

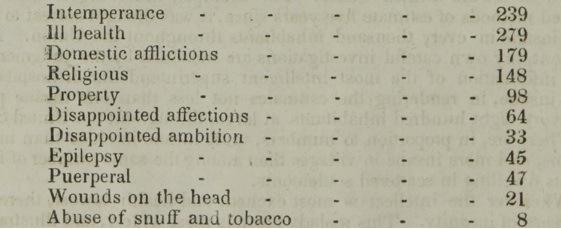

Reading the booklet (available in full through the National Library of Medicine), it became clear that these “reasons for admission” were actually the proximate causes to which 19th-century patients or their families attributed their “madness” (which Dix often described in blanket terms as “insanity” or “mania”).

From Memorial of D.L. Dix: praying a grant of land for the relief and support of the indigent curable and incurable insane in the United States, Dorothea Dix, 1848; digitized by the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

So, of course, 19th-century West Virginians weren’t committed because their “parents were cousins” or they had “women trouble,” but because they suffered from mental illness. They had cited those life events as answers to questions about the origins of mental instability. At a time when people had stopped believing in demonic possession, but had not yet evolved a more specific way to diagnose and treat mental illness, such intake information reflected a new search for the causes of “insanity.”

Dix, for her part, thought that the political environment of the United States encouraged “mania”:

Wherever the intellect is most excited, and health lowest, there is an increase of insanity. …This malady prevails most widely, and illustrates its presence most commonly in mania, in those countries whose citizens possess the largest civil and religious liberty; where, in effect, every individual, however obscure, is free to enter upon the race for the highest honors and most exalted stations.

Dix also found sources of “insanity” in “religious excitement” (including Millerism) and civil disruption (“riots and firemen’s mobs in Philadelphia,” “tumultuous and riotous gatherings in Ireland”).