Courtesy: Minnesota Historical Society.

The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

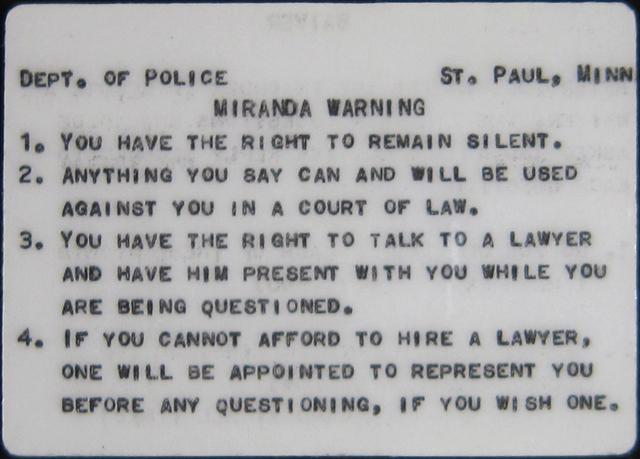

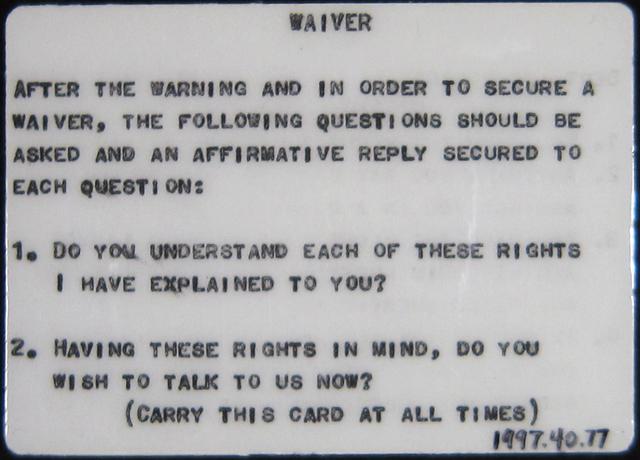

While the cadence of the Miranda warning that begins “You have the right to remain silent…” is now so familiar that most Americans can recite it by heart, the language, penned by California officials, only rooted itself in American culture when an enterprising D.A. sold these “Miranda warning cards” to law enforcement agencies across the U.S. in the late 1960s.

On June 13, 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court issued the landmark Miranda v. Arizona decision, which overturned Miranda’s conviction in the 1963 kidnapping and rape of a 17-year-old girl, to which he confessed while under interrogation as a suspect in an $8 armed robbery. Miranda established that suspects must be advised of their Fifth Amendment rights to counsel and against self-incrimination before police questioning.

But nowhere did the Court mandate specific language for implementation. In the summer of 1966, state Attorney General Thomas C. Lynch called a meeting of California’s district attorneys to discuss developing an administrative standard. “We’re going to have to have a warning,” he reportedly told the assembled D.A.s. ”Now who’s going to write the warning?” He assigned Assistant Attorney General Doris H. Maier (the first woman to serve in that post) and Nevada County D.A. Harold Berliner to the task. Within a matter of hours, Maier and Berliner had drafted what was likely the first written version of the warning.

Though Berliner practiced law to support his large family, his passion lay in fine art and letterpress printing. Sensing a business opportunity, he began printing Miranda warning cards on sturdy vinyl (so that they could go through the wash) and sent samples to “every law enforcement agency in the nation.” Berliner sold tens of thousands, putting his script in the hands of police officers across the nation.

Amplifying the effect was television producer and actor Jack Webb’s decision to fold the Miranda rule into the 1967 revival of Dragnet. Because he insisted on accuracy and received significant technical assistance from the LAPD, he used Berliner’s script, the California standard, and influenced dozens of other shows in the process.

Over the years, the Supreme Court has heard at least a half dozen challenges to the substance of Miranda. The familiar language of the Miranda warning, as written by Maier and Berliner, has, as the Rehnquist court declared in 2000’s Dickerson v. United States, become “embedded in…our national culture”—an omnipresence that supported the justices’ argument that Miranda had precedent and should not be overturned. Despite that acknowledgement, the Court also affirmed in Dickerson that the “Constitution does not require police to administer the particular Miranda warnings” that are so familiar today.