The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

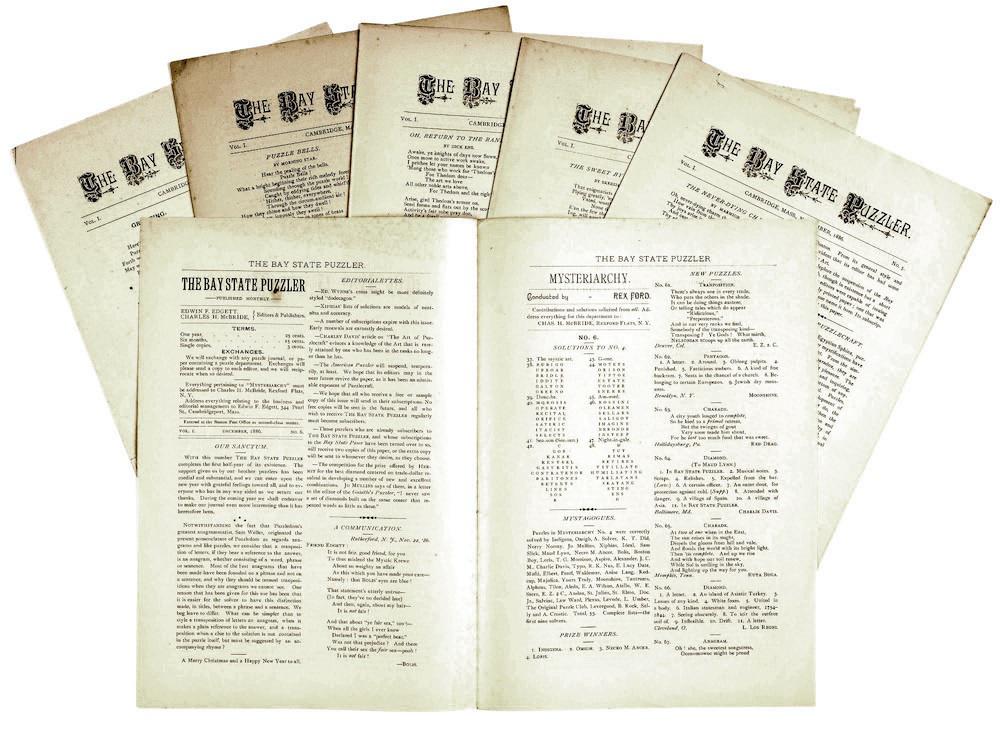

Here’s one issue of the Bay State Puzzler, which had a six-issue run in 1886 under the guiding hand of editors Edwin F. Edgett (apparently then 19 years old) and Charles H. McBride (apparently then 17).

The availability of novelty toy printing presses, which cost between $15 and $50 at the end of the 19th century (or $375 to $1,250 in today’s dollars), fueled the growth of amateur journalism among middle- and upper-class adolescents in the late 19th century. According to historian Paula Petrik, the amateur journalists, who were mostly (though not all!) young men, communicated with each other through the mail, exchanging issues and printing and reprinting each other’s letters and contributions.

This was a self-referential culture. “By the mid-1870s,” writes literary historian Lara Langer Cohen,

most of [the contents of the papers] revolved around the activities of amateurdom.: editorials on the state of the ‘dom, reviews of other newspapers, in-jokes aimed at fellow editors, reports from local, state, and national amateur conventions, histories of amateur journalism, profiles of prominent amateur editors, and so on.

The Bay State Puzzler is no exception, and its editors were active in the thriving puzzler paper subculture (the American Antiquarian Society holds a surprisingly long list of amateur puzzler newspaper titles from the 1880s and 1890s). The left-hand page in this spread lauds other puzzlers with particular sets of skills, prints poems from fellow puzzlers, and weighs in on active controversies of the field (when is an anagram an anagram, and when is it a transposition?) The right-hand page offers solutions to past puzzles, lists the names of successful solvers, and prints new puzzles.

In his post on the Bay State Puzzler, Vincent Golden, the American Antiquarian Society’s curator of newspapers and periodicals, explains the structure of the diamond puzzle, a common feature of puzzler papers. The solver must stack answers to the prompts in a diamond shape. The clues needed to read both vertically and horizontally. Golden offers a solved example in his post, as well as several sets of diamond prompts from the Puzzler’s other issues.

Click on the image to reach a zoomable version.

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.