The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

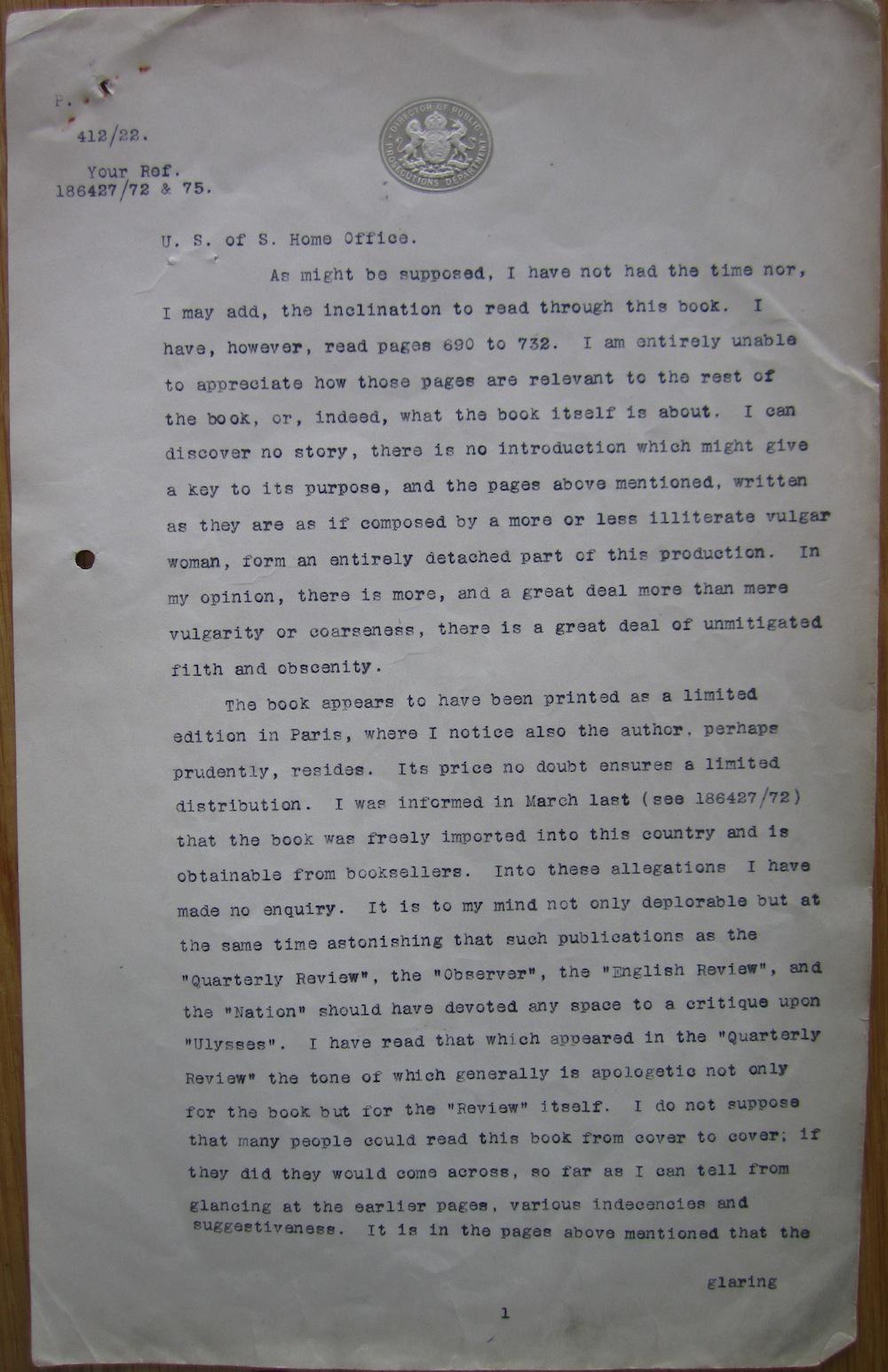

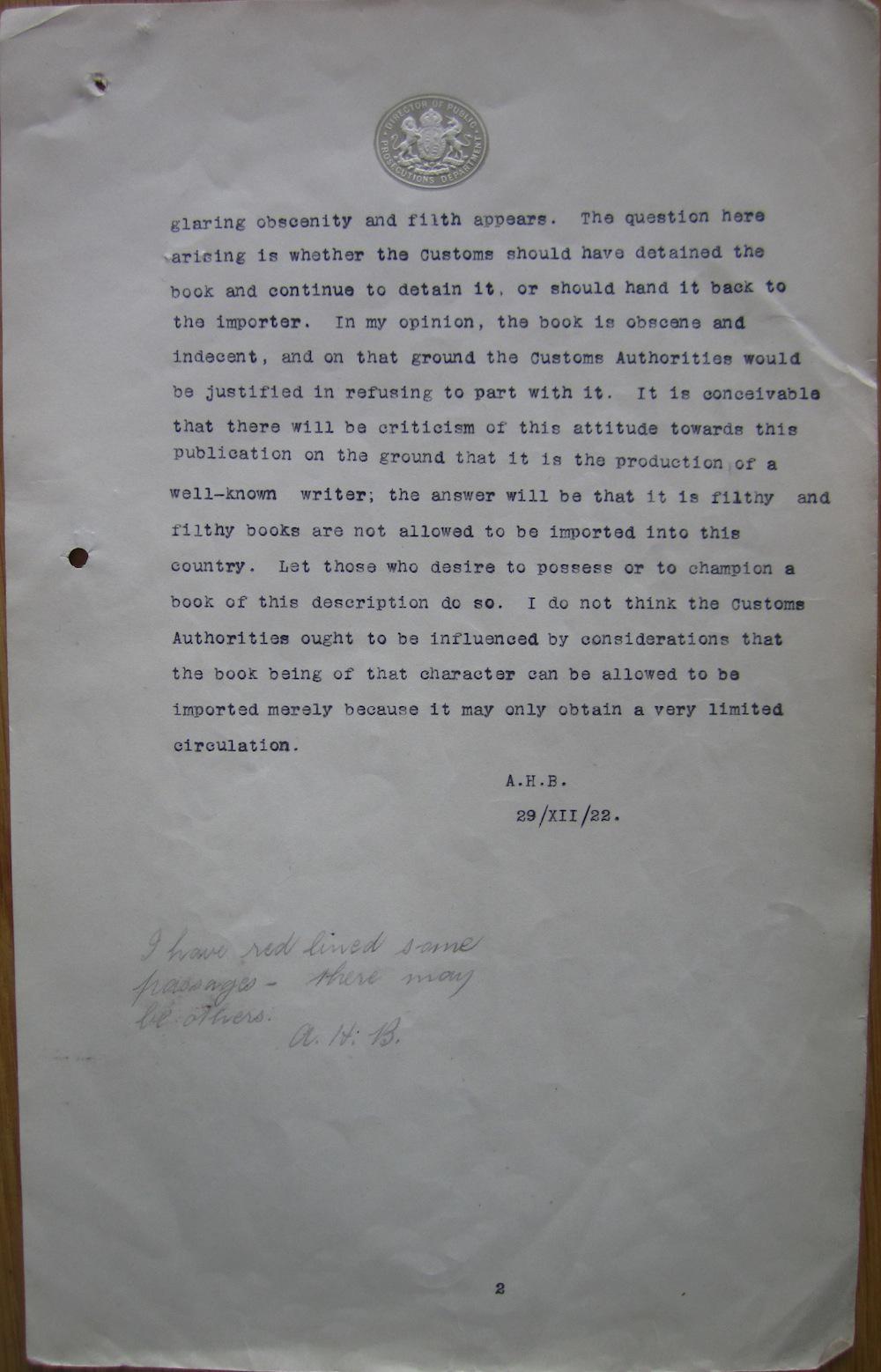

In this 1922 letter, the British Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Archibald Bodkin, issued an official opinion on James Joyce’s book Ulysses, calling it a “filthy book” and declaring that it should “not be allowed to be imported into the country.” The government adopted Bodkin’s recommendation, and banned Ulysses from the UK.

By that year, the just-published Ulysses had already provoked action from one government. In 1921, American courts had declared that the excerpts of Ulysses that had been serialized in the modernist literary magazine The Little Review were in violation of the Post Office’s anti-obscenity code.

When the full work was printed in a very limited edition in Paris in 1922, British newspapers protested, running outraged editorials. After a customs official seized a rare copy of the book at a London airport, skimmed its content, and found it salacious, the Home Office asked Bodkin to draft an official government opinion on the matter.

“Sir Archibald was a man of unwavering Victorian sensibilities,” Kevin Birmingham writes in his new history, The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses (reviewed in the Slate Book Review last week). “On the rare occasions when he told a bawdy joke, he drained away the humor by delivering the punch line with a disapproving glare.” The letter, written solely as a reaction to the book’s final chapter (Episode 18: Penelope), reflects the prosecutor’s starkly traditional attitude toward the experimental, sexually frank work of the Irish writer.

The results of Bodkin’s pronouncement weren’t long in coming. In January 1923, customs officers seized and burned 500 copies of the book, which its publishers had been hoping to smuggle through Britain into the United States. The novel wasn’t printed in Britain until 1936, two years after Random House sought, and won, the right to publish the work in the States.

The National Archives (of the UK), Home Office records.

The National Archives (of the UK), Home Office records.