The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

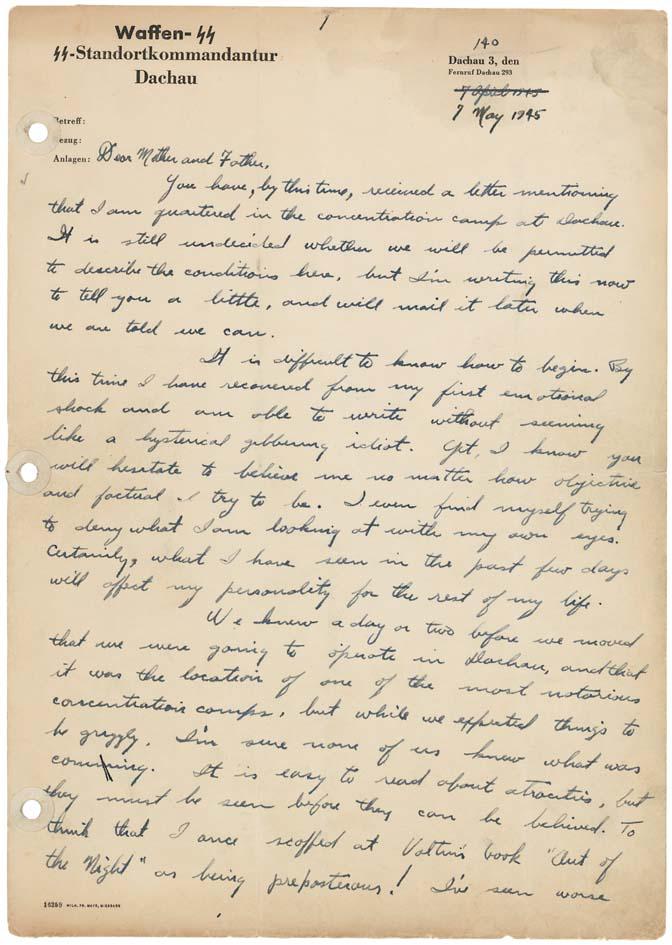

This 1945 letter, from Harold Porter to his mother and father in Michigan, describes the situation at the Dachau concentration camp after liberation. The letters that Pfc. Porter, who served as a medic with the 116th Evacuation Hospital, wrote to his parents are now archived at the Eisenhower Presidential Library [PDF].

In the months before the Americans’ arrival, the Nazis had begun directing transports of prisoners from other camps to Dachau. The chaos of the German defeat disrupted Nazi efforts to dispose of the bodies of those prisoners who had died, many of whom had suffered from untreated tuberculosis and typhus. When the 45th Division’s 157th Infantry Regiment arrived on April 29, 1945, the camp was full of prisoners, sick, dying, and dead. The 116th entered the camp two days later.

Historian Robert Abzug, in his book about the Americans who were present at the liberation of the concentration camps, writes that these witnesses were totally unprepared to register the magnitude of the atrocities of the Holocaust. Even for those who had believed scattered earlier eyewitness reports, the actuality of the situation went far beyond any predictions.

Americans like Porter struggled to explain what they saw to people back home. The National Archives describes Porter’s letter as “unsparing and graphic,” and it is indeed that. Written on the former camp commandant’s letterhead, the letter is by turns despairing and deeply upsetting. Porter seems determined to make his parents understand what it was like at Dachau, though he sees the task as quasi-impossible: “The realness of the whole mess is just gradually dawning on me, and I doubt if it ever will on you.”

Thanks to Porter’s daughter Jean Silesky and her siblings for granting permission to publish the letter.

National Archives/Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library.

Transcript below. Again, a warning: The letter contains gruesome details that some may find disturbing.

7 May 1945

Dear Mother and Father,

You have, by this time, received a letter mentioning that I am quartered in the concentration camp at Dachau. It is still undecided whether we will be permitted to describe the conditions here, but I’m writing this now to tell you a little, and will mail it later when we are told we can.

It is difficult to know how to begin. By this time I have recovered from my first emotional shock and am able to write without seeming like a hysterical gibbering idiot. Yet, I know you will hesitate to believe me no matter how objective and focused I try to be. I even find myself trying to deny what I am looking at with my own eyes. Certainly, what I have seen in the past few days will affect my personality for the rest of my life.

We knew a day or two before we moved that we were going to operate in Dachau, and that it was the location of one of the most notorious concentration camps, but while we expected things to be grizzly [sic], I’m sure none of us knew what was coming. It is easy to read about atrocities, but they must be seen before they can be believed. To think that I once scoffed at Valtin’s book Out of the Night as being preposterous! I’ve seen worse sights than he described.

The trip south from Göttingen was pleasant enough. We passed through Donauworth and Aichach and as we entered Dachau, the country, with the cottages, rivers, country estates and Alps in the distance, was almost like a tourist resort. But as we came to the center of the city, we met a train with a wrecked engine - about fifty cars long. Every car was loaded with bodies. There must have been thousands of them - all obviously starved to death. This was a shock of the first order, and the odor can best be immagined [sic]. But neither the sight nor the odor were anything when compared with what we were still to see.

Marc Coyle reached the camp two days before I did and was a guard so as soon as I got there I looked him up and he took me to the crematory. Dead SS troopers were scattered around the grounds, but when we reached the furnace house we came upon a huge stack of corpses piled up like kindling, all nude so that their clothes wouldn’t be wasted by the burning. There were furnaces for burning six bodies at once, and on each side of them was a room twenty feet square crammed to the ceiling with more bodies - one big stinking rotten mess. Their faces purple, their eyes popping, and with a hideous grin on each one. They were nothing but bones & skins. Coyle had assisted at ten autopsies the day before (wearing a gas mask) on ten bodies selected at random. Eight of them had advanced T.B., all had typhus and extreme malnutrition symptoms. There were both women and children in the stack in addition to the men.

While we were inspecting the place, freed prisoners drove up with wagon loads of corpses removed from the compound proper. Watching the unloading was horrible. The bodies squooshed and gurgled as they hit the pile and the odor could almost be seen.

Behind the furnaces was the execution chamber, a windowless cell twenty feet square with gas nozzles every few feet across the ceiling. Outside, in addition to a huge mound of charred bone fragments, were the carefully sorted and stacked clothes of the victims - which obviously numbered in the thousands. Although I stood there looking at it, I couldn’t believe it. The realness of the whole mess is just gradually dawning on me, and I doubt if it ever will on you.

There is a rumor circulating which says that the war is over. It probably is - as much as it will ever be. We’ve all been expecting the end for several days, but were not too excited about it because we know that it does not mean too much as far as our immediate situation is concerned. There was no celebration - it’s difficult to celebrate anything with the morbid state we’re in.

The Pacific theater will not come immediately for this unit; we have around 36,000 potential and eventual patients here. The end of the work for everyone else is going to be just the beginning for us.

Today was a scorching hot day after several raining cold ones. The result of the heat on the corpses is impossible to describe, and the situation will probably get worse because their disposal will certainly take time.

My arm is sore from a typhus shot so I’m ending here for the present. More will follow later. I have lots to write about now.

Love, Harold.

Update, May 2, 2014: The original version of this post transcribed the name of the book Porter referred to in paragraph three as “Voltaire’s Art of the Night.”