The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

These photos come from a new book of photographs from Detroit’s wartime factories, Images from the Arsenal of Democracy, by historian Charles K. Hyde. The book takes its title from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Dec. 29, 1940 fireside chat, in which the president called upon Americans to support the new industrial effort to arm American allies: “We must be the great arsenal of democracy. … We must apply ourselves to our task with the same resolution, the same sense of urgency, the same spirit of patriotism and sacrifice, as we would show were we at war.”

The manufacturing of tanks was a particular priority, as the German army had by far outpaced its adversaries in this area. In the late 1930s, Hyde writes, “the U.S. Army was not using tanks in any combat capacity … There were no facilities in the United States to manufacture tanks—not even in small quantities.” As late as 1939, the U.S. Army Ordnance Department awarded tank contracts to companies that manufactured railroad equipment, before determining that automotive concerns would be far more capable of the level of mass production that was needed.

These images, taken by photographers working for the Automotive Council for War Production, capture some workers who were part of the effort to close the tank gap.

Automotive Council for War Production Collection, National Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library.

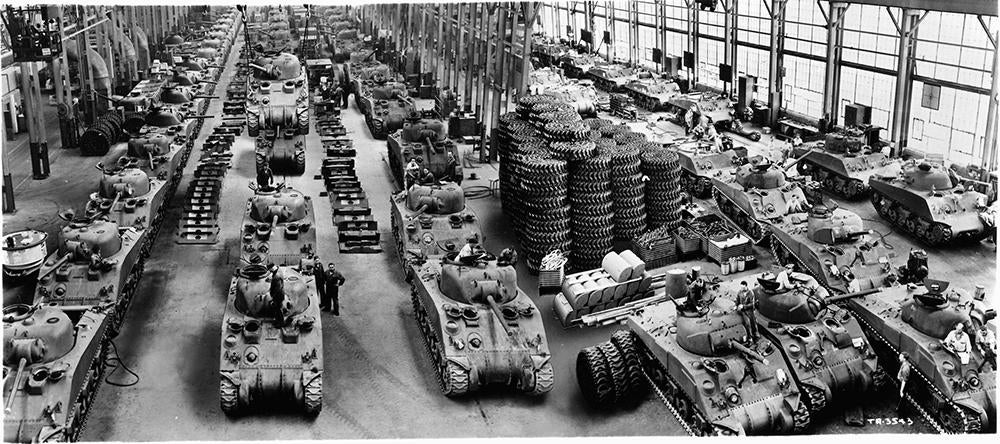

M3 General Grant tanks nearing completion at the newly-built Chrysler Tank Arsenal. The Army Ordnance Department always perceived the M3 as an inadequate design, relied upon as a stopgap only. The M3’s major defects: the main 75-mm gun was mounted on the right corner of the hull, and had only a 15-degree field of fire. The tank was too tall, and the riveted turret and hull, Hyde writes, “weakened its armament and was a serious hazard to the crew and nearby infantry if it suffered a direct artillery hit.” Nonetheless, during 1941 and 1942, the M3 was the best available design for a medium-sized tank that could be produced quickly.

Charles K. Hyde, private collection.

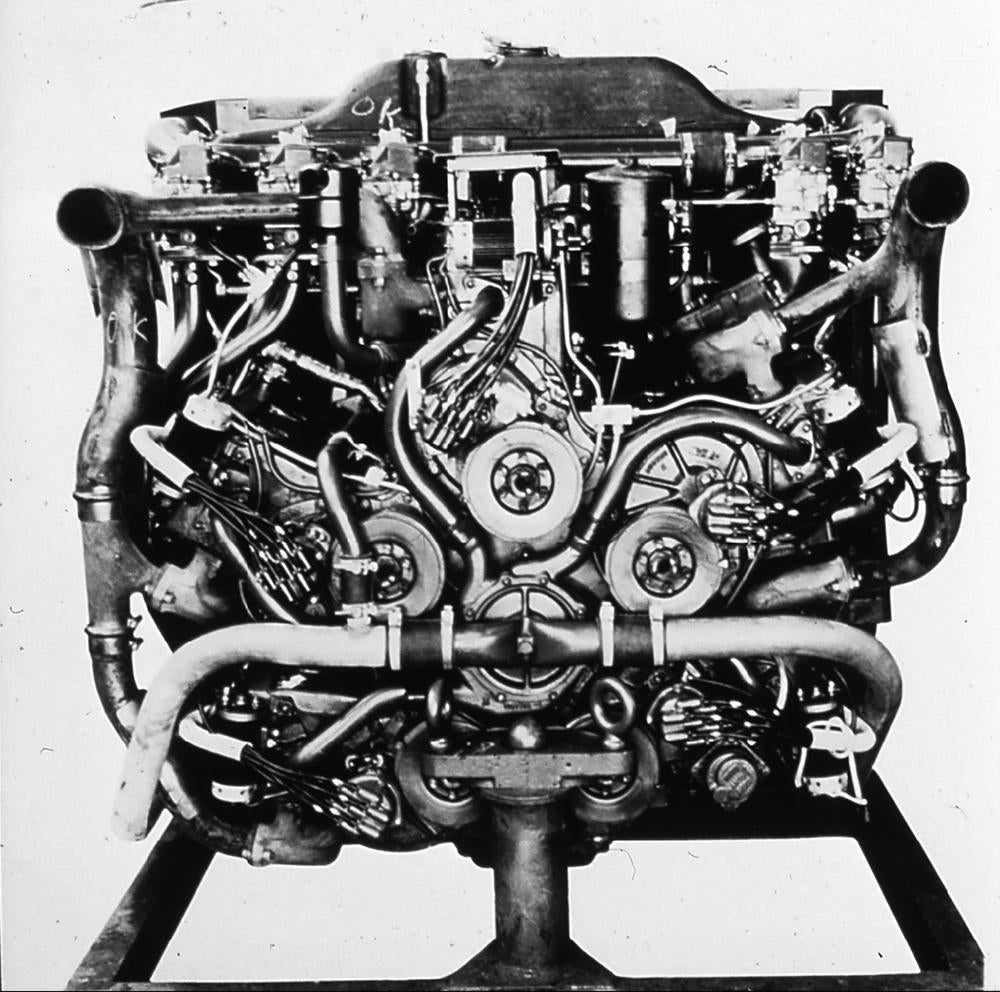

The “multibank engine” designed by Chrysler for the M3, and used in the M4 as well. A modification of an automobile engine, the multibank engine combined five six-cylinder engines by linking them to a single driveshaft. Hyde notes that critics called the engine “the eggbeater”; it was only used in the M3 during the spring and summer of 1942, before the M3 was superseded by the M4.

Automotive Council for War Production Collection, National Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library.

The next-generation M4 General Sherman tank, in its last stages of assembly at the Chrysler Tank Arsenal, June 1944. Unlike the M3, the M4’s 75-mm gun could swivel 360 degrees. In another improvement, the hull was welded, rather than riveted. The pile of jagged-looking rolls in the middle of the photo is a stack of tank treads.

Automotive Council for War Production Collection, National Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library.

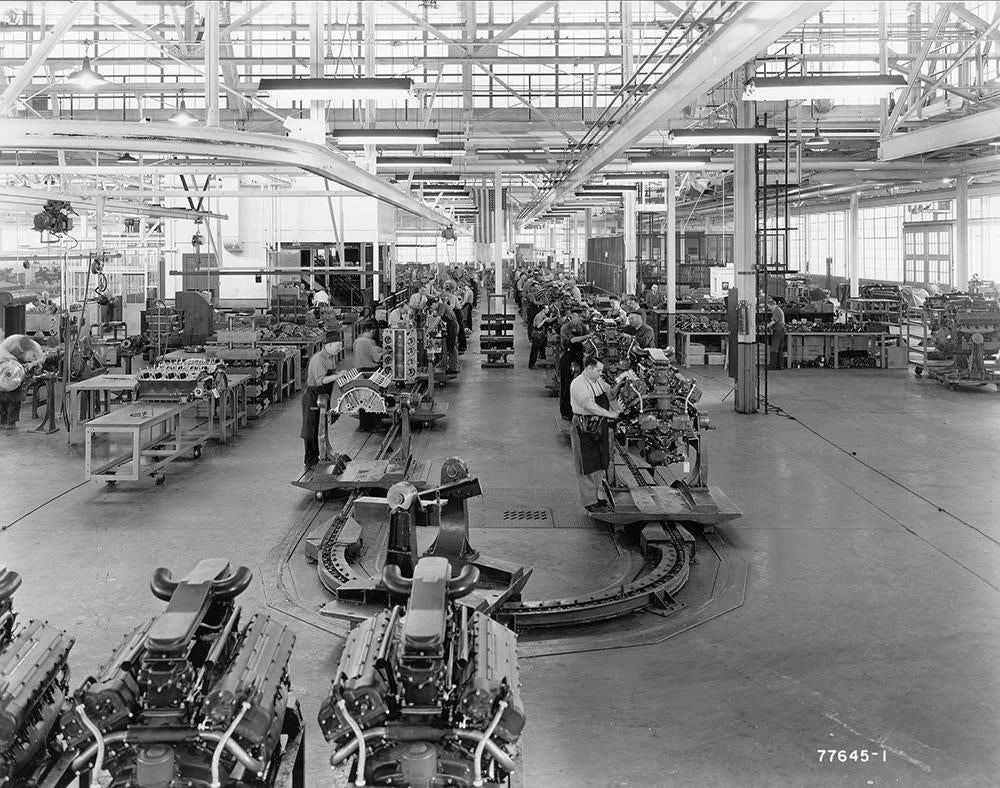

The hunt for the ideal tank engine persisted throughout the war, and the M4 Sherman used six different kinds of diesel and gasoline engines. Here are workers on the assembly line at the Detroit Diesel plant, with a General Motors-designed twin diesel engine.

Automotive Council for War Production Collection, National Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Workers at Ford’s River Rouge plant assembling Ford’s V-8 tank engines. “Rated at 450 horsepower, the Ford engine had the best power-to-weight ratio of all tank engines,” Hyde writes. “It was seen by army personnel as reliable and easy to maintain.”

Correction, March 25, 2014: This post originally misidentified the location of the 75-mm gun on the M3, and failed to mention that the multibank engine was also used in the M4. Additionally, a photograph originally included in the post was misidentified in the source material as showing a wartime assembly line building Pershing tanks (in actuality, the tanks were Pattons, meaning that the photo must have been taken in the postwar era). The image has been removed and replaced with the last photo here, of the River Rouge workers.