The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

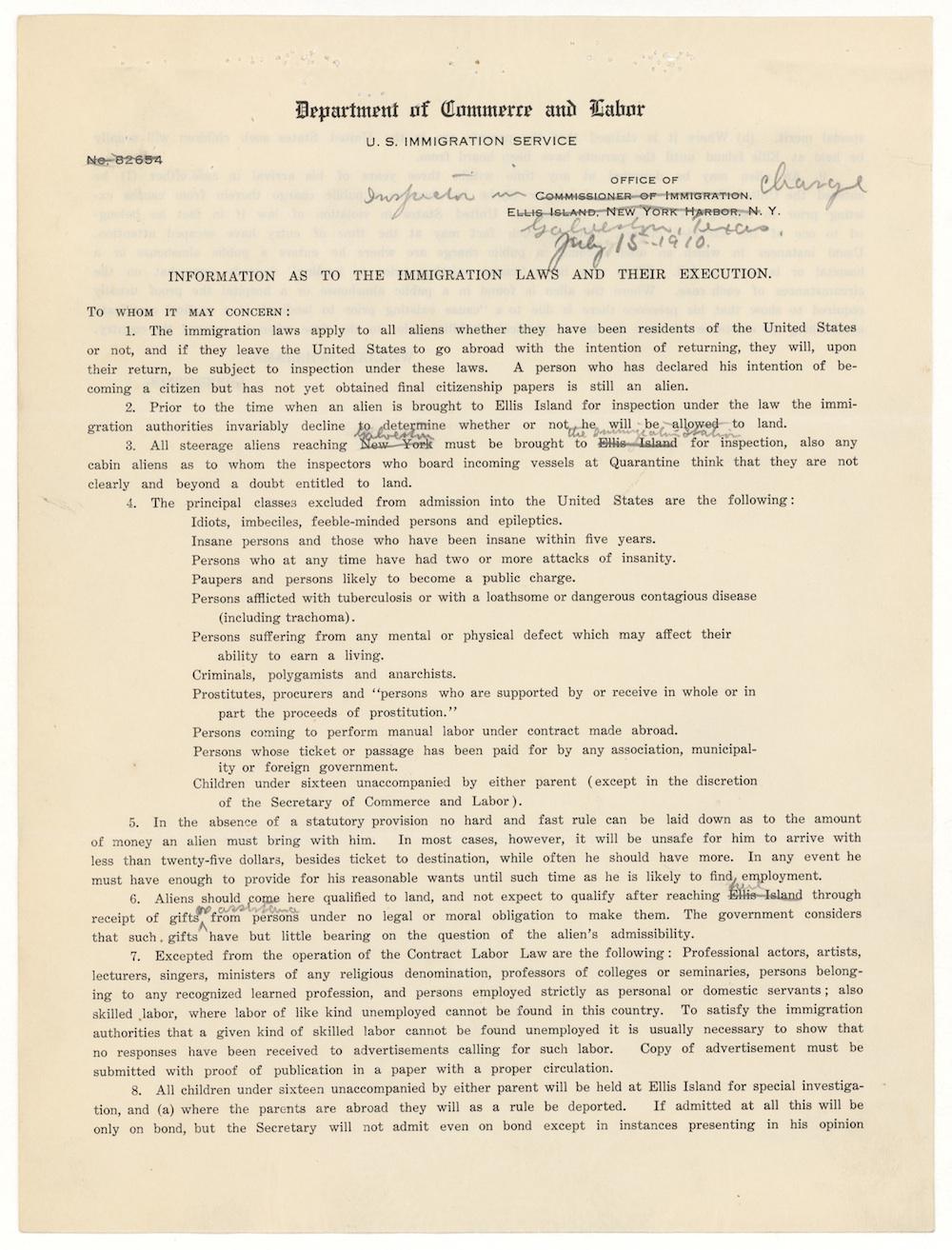

This 1910 letter, drafted by the Department of Commerce and Labor’s U.S. Immigration Service for the Inspector in Charge in Galveston, Texas, summarizes the provisions of current immigration policy. The letter was originally intended for use by the commissioner at Ellis Island. Penciled in are suggested adaptations for Galveston, a port city that served as the gateway for 150,000 immigrants between the mid-nineteenth century and World War I.

The most stringent quotas on American immigration, enacted as part of the Immigration Act of 1924, were still in the future at the time of this letter’s publication. At the same time, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had been extended under the provisions of the Geary Act, making it hard for Chinese workers to enter the country. And many people, including prominent lawmakers and public figures, had raised objections to the growing number of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe. Multiple proposals to require a literacy test—taken in any language—for entry to the United States had floated through Congress for twenty years; one would finally be signed into law in 1917.

The influence of eugenic thought, which deplored the weak, on immigration policy is clear in this list of people who wouldn’t be allowed in, including “idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded persons and epileptics,” as well as people who have had “two or more attacks of insanity.” The judgment of the interrogating inspector and surgeon would determine whether the prospective immigrant was “suffering from any mental of physical defect which may affect their ability to earn a living.”

The letter includes interesting exceptions to the rule that people couldn’t enter with a pre-arranged manual-labor job “under contract made abroad” (a stipulation meant to cut down on the practice of recruiting cheap labor from overseas). Professional performers, lecturers, ministers, professors, and “persons belonging to any recognized learned profession” were all exempted.

National Archives.

National Archives.