The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

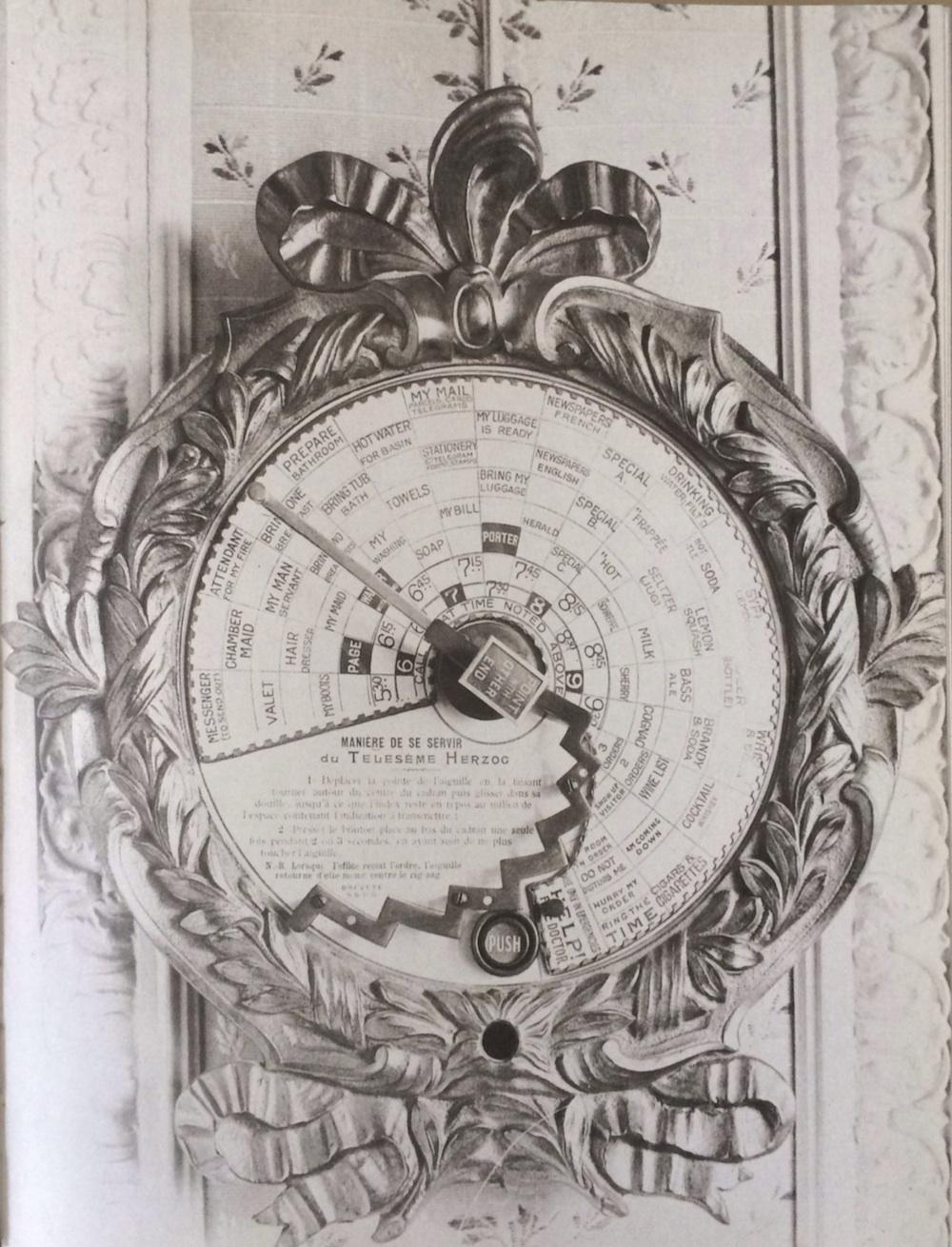

This elaborate object is a “Teleseme,” manufactured by New York’s Herzog Teleseme Company and used in Paris’ Élysée Palace Hotel in the 1890s. The Teleseme was designed so that hotel guests could inform staff of a staggering array of wants and needs, without ever speaking with a person. Instructions asked guests to move the pointer, which could be collapsed and extended, to the square that represented their desire (“wine list,” “my maid,” “lemon squash”), and then push the button at the bottom.

Hotels, especially the big luxury hotels of the mid-19th through mid-20th centuries, have historically adopted new technologies of communication quite quickly. An apparatus like the Teleseme set would have been a marker of fanciness and refined service—for a few decades, at least.

The back-end operation of the Teleseme set, as described in the magazines The Electrician in 1895 and Electrical Engineer in 1896, was complex. In the hotel office, an attendant staffing the desk kept an eye on a small display that featured a numbered compartment for each room, in which a platinum disc was suspended in a liquid. A Teleseme set that mimicked the one found in the guest rooms stood nearby.

When a room’s Teleseme set was activated, the attendant received information about the guest’s request in two stages. An electrode connected to the room’s compartment dispersed a current that caused the disc to discolor, alerting the attendant as to which room number required attention. The attendant would turn on the receiving Teleseme set, and the receiver would mimic the selection made by the guest. In possession of both the room number and the guest’s desire, the attendant would alert the kitchen, laundry, or concierge of the guest’s request.

In 1914, M.J. King, an agent who had sold private branch exchanges (building-wide telephone systems) to hotels, reminisced about the difficulty in getting establishments who were used to the Teleseme to replace it with his product. The systems were cheap to operate, King reported, and the Herzog Company had been able to persuade many hotels to buy into the idea early on.

King’s job was made easier, however, by the fact that the Teleseme was not without its drawbacks. While a customer could correct a human operator’s misapprehension over the phone, a lady guest who thought she’d ordered iced water over the Teleseme could find champagne at her door—a miscommunication that cost time and labor. Any complications to a request (two pitchers of iced water, please) were impossible to express using the Teleseme system.

Eventually, the Teleseme was superseded in the luxury hotel market by the private branch exchange, which was a more flexible and exact system of communication.

Image courtesy of the Marc Walter Collection.