The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

From 1935 to 1945, the government’s Farm Security Administration paid photographers to document conditions on farms across the United States. Some of the resulting images, made by artists including Walker Evans, Gordon Parks, Dorothea Lange, and Ben Shahn, have become iconic representations of life during the Depression. But the agency produced such a large number of photographs (the Library of Congress counts 175,000 negatives in their FSA collection) that it’s easy to lose track of the specificity of the lives that were being documented.

Joe Manning, an author, researcher, and retired social worker, has made a project out of uncovering the backstories of some of the FSA photographs’ subjects. Manning has a particular affection for the photos made by John Vachon, a lesser-known FSA artist who started as a file clerk at the agency and transitioned into traveling and taking photographs in 1937. Vachon didn’t keep very good records of his travels, and many of his photographs are unaccompanied by much information about their subjects.

One of Manning’s methods of information-gathering is to persuade local papers in the area where the photo was taken to run an article asking for relatives to step forward. In many cases, Manning has been able to find family of the subjects—or even the subjects themselves—to interview.

See more of the FSA photos Manning has investigated, including images whose backstories are still unknown, here.

This unidentified “farm girl” turned out to be Claudine Abele, born in 1928, an only child who lived on the same farm until she was 60, except for a three-year stint twenty miles away. When Manning interviewed Abele’s son, Roger, in 2008, he was still farming the same land.

“I don’t remember being photographed,” Claudine Abele told Manning, “but as I look at it, I think I remember that dress. My neighbor girl, she was in the eighth grade when I was in the first grade, and I got a lot of her hand-me-down clothes.”

Abele responded to Manning’s questions about hardship with stoicism. She shared memories of crop failure: “I remember that it had hailed, and we went out and saw that we had lost the wheat crop. I could see the holes that had been pressed into the ground from the hailstones.”

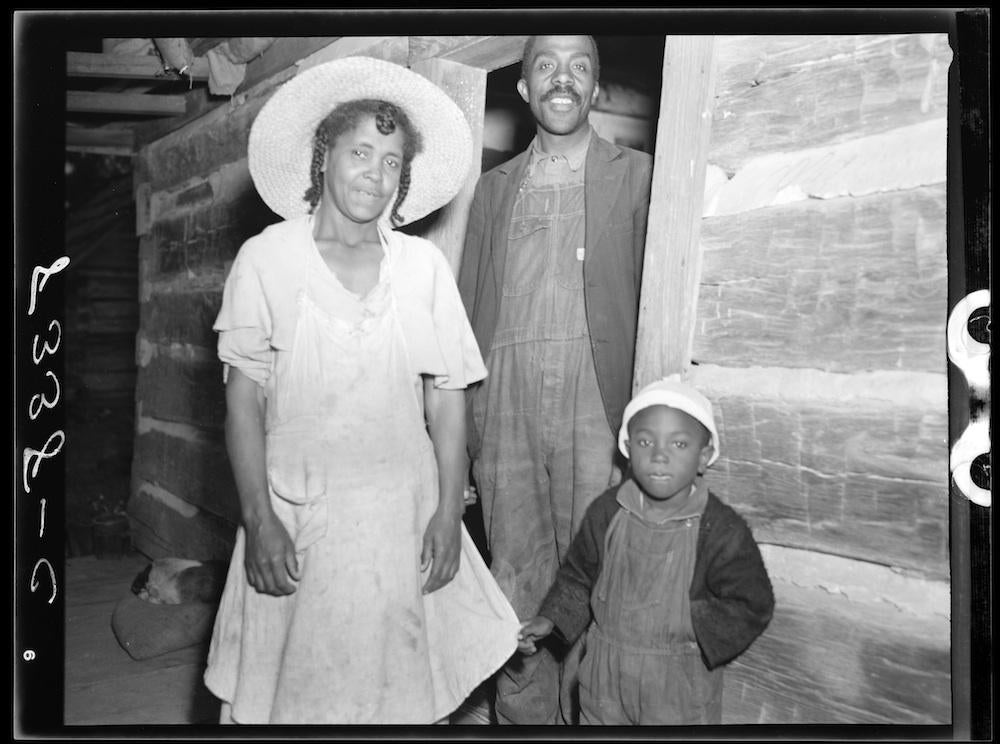

Nat Williamson, previously a sharecropper, was the first black farmer to receive an FSA loan to purchase his farm. While the agency gave him 40 years in which to pay off the $2,980 loan, he managed to do so in seven.

Manning’s interview with Vivian Sexton, one of Williamson’s granddaughters, revealed that Williamson’s father was born into slavery right before emancipation. The family stayed in Guilford and Caswell Counties, in North Carolina, after the Civil War, and many still live there. The land remains in the family, though it’s no longer being used for agriculture. Several of Williamson’s children and grandchildren have built houses on parcels of the former farm.

Sexton recalled, of the years after the Vachon photos were taken: “When we were growing up, the only thing we bought from the store was like sugar and salt and coffee. Everything else was grown or made. We raised pigs and chickens. My grandfather grew sugarcane and made molasses. We had an apple orchard. He sold butter and eggs, apple cider, vegetables, watermelons and peaches. He had a farm stand in the summer.”

Perhaps the most bittersweet story that Manning uncovered is that of the Bettenhausen family, whose matriarch, Emma, features in these photos taken in McIntosh County, North Dakota. Emma Bettenhausen let Vachon photograph her going about her daily labors: ironing, feeding the stove with corn-cob fuel, making bread, stocking the cellar with an impressive array of canned goods.

Manning found that Emma Bettenhausen had given birth to 15 children when the photo was taken, and that she was then four months pregnant. She died of cancer eight months after her last child was born. “These are the only significant photographs of the family taken at the time,” Manning writes.

Manning interviewed Richard Bettenhausen, the youngest child, who was an infant when his mother died. “For nearly my entire life, I’ve been putting bits and pieces together of what my mother was really like,” Bettenhausen said. His older sisters “made pretty big sacrifices to jump into [the] role of being a homemaker” after his mother died, while the younger children had the job of “making sure there was water in the house,” which didn’t have indoor plumbing.

“John Vachon took quite a few pictures of your mother doing household chores,” Manning said. “She didn’t look self-conscious. She looked like she was content to do whatever she was doing, and that she wasn’t bothered by the camera. I think your mother was quite beautiful.” Bettenhausen replied: “That’s exactly how my older sisters described my mother.”