The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

The strange 18th-century manuscript called the Clavis Inferni (key of hell) is filled with invocations, cryptic sigils, and paintings of supernatural beings. The book defies interpretation—as it was meant to do.

The magical tradition has always been an elitist one, based on the notion that only a select few are worthy of understanding the secrets of nature. Magical sigils (symbols) made in the early modern period, like those in the Clavis Inferni, were meant to be obscure, to hide those secrets. The German occultist Cornelius Agrippa, who was a magic practitioner as well as a soldier, physician, and theologian, called such sigils “unknowable letters and writings, preserving the secrets of the Gods, and names of spirits from the use and reading of prophane [sic] men.”

Yet that doesn’t mean that we can’t guess at their meaning. The Clavis Inferni, which you can read in its entirety through the Wellcome Library, features Latin passages that invoke spirits associated with cardinal directions: “Paymon, the King of the West,” “Uricus, the King of East,” and so forth. There are Latin prayers for banishing summoned creatures (“Go away now most calmly to your place, without murmur and commotion”) as well as Hebrew invocations of God. Even writing that is neither Latin nor Hebrew is decipherable: much of it is in a magical alphabet created by Agrippa.

We know almost nothing about the book’s provenance or the true identity of its creator (“Cyprian” was among the most common pseudonyms for authors of magical texts). The Wellcome Library draws a link to the “Black School at Wittenburg,” a school for sorcerers described in Scandinavian folklore. We might surmise that it was collected by Henry Dawson Lea, a Victorian who transcribed another manuscript in the Wellcome collection entitled “Five Treatises upon Magic.” Yet the Clavis Inferni doesn’t give up its mysteries easily.

You can read more about this fascinating book over at The Appendix, the online history journal of which I’m an editor, and share any information and translations in the comments section or on our Twitter or Facebook pages—we’d love to learn more.

Wellcome Library. London.

Like many magical texts, the Clavis Inferni is grounded in the Bible and kabbalah. The first image references the Book of Revelations’s description of a figure surrounded by “seven golden candlesticks” whose “head and his hairs were white like wool” and “his eyes were as a flame of fire.” The Wellcome Library identifies this figure as the archangel Metatron, but the iconographic references to Revelations 1:12-1:15 make me suspect it’s a portrayal of the second coming of Christ. Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni (18th century), Page 3.

Wellcome Library, London.

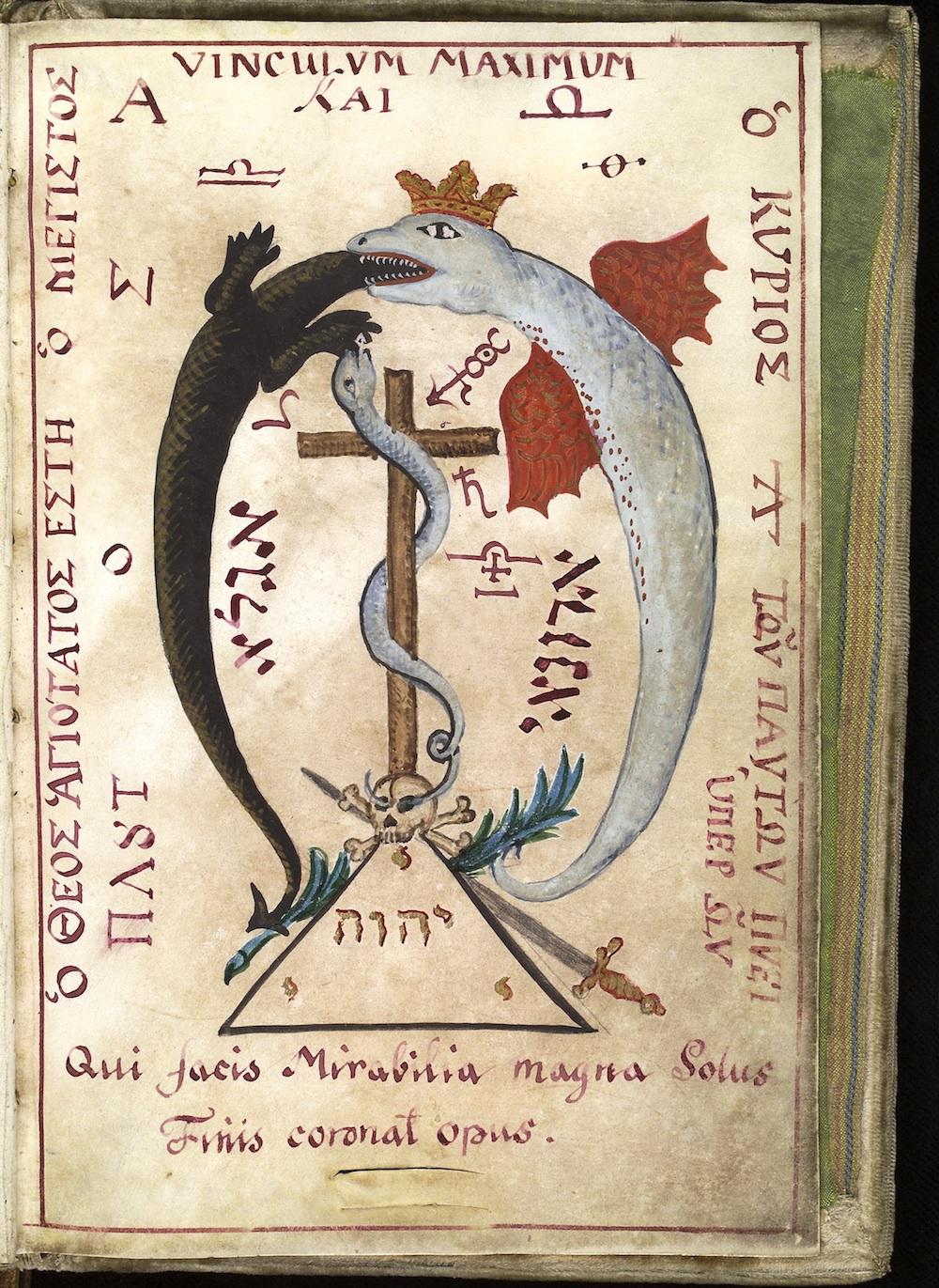

Alchemical signs, Hebrew and Greek surround a crowned white dragon swallowing a black lizard. The sword and branch in this image reference God’s twinned powers to create destruction or peace. The caption roughly translates to “you who do great deeds alone/ the end shall crown the work.” Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni, Page 20.

Wellcome Library, London.

The origin of the name “Uricus, “king of the east,” is obscure. Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni, Page 7.

Wellcome Library, London.

“Paymon” (likewise, an obscure reference) “as king of the west.” Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni, Page 7.

Wellcome Library, London.

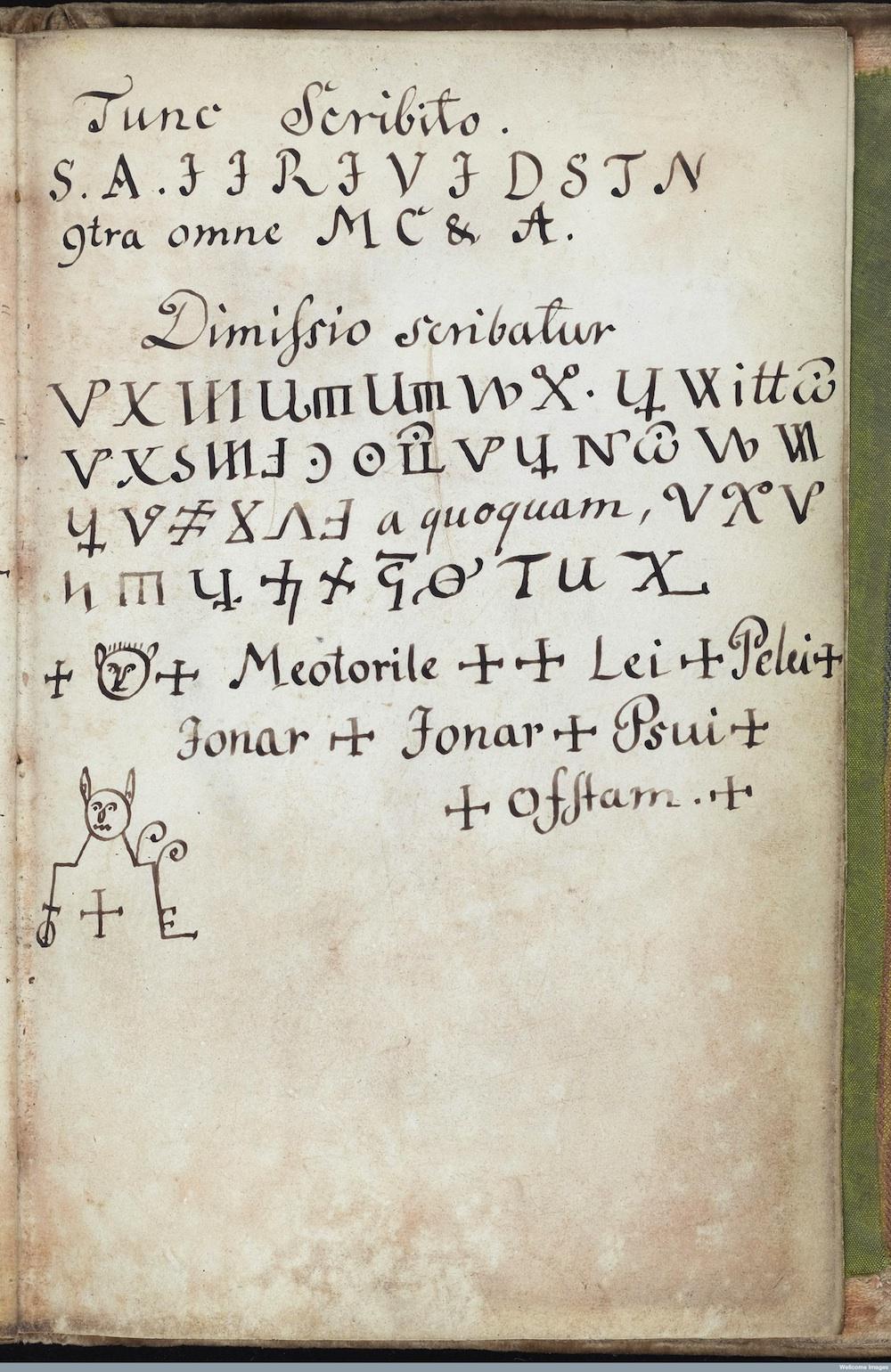

A page of text in Latin and Agrippa’s invented alphabet continuing a passage labeled “Fuga Daemonium,” apparently instructions on how to banish a demon (perhaps the muppet-like creature pictured in the text?). Clavis Inferni, Page 18.