The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

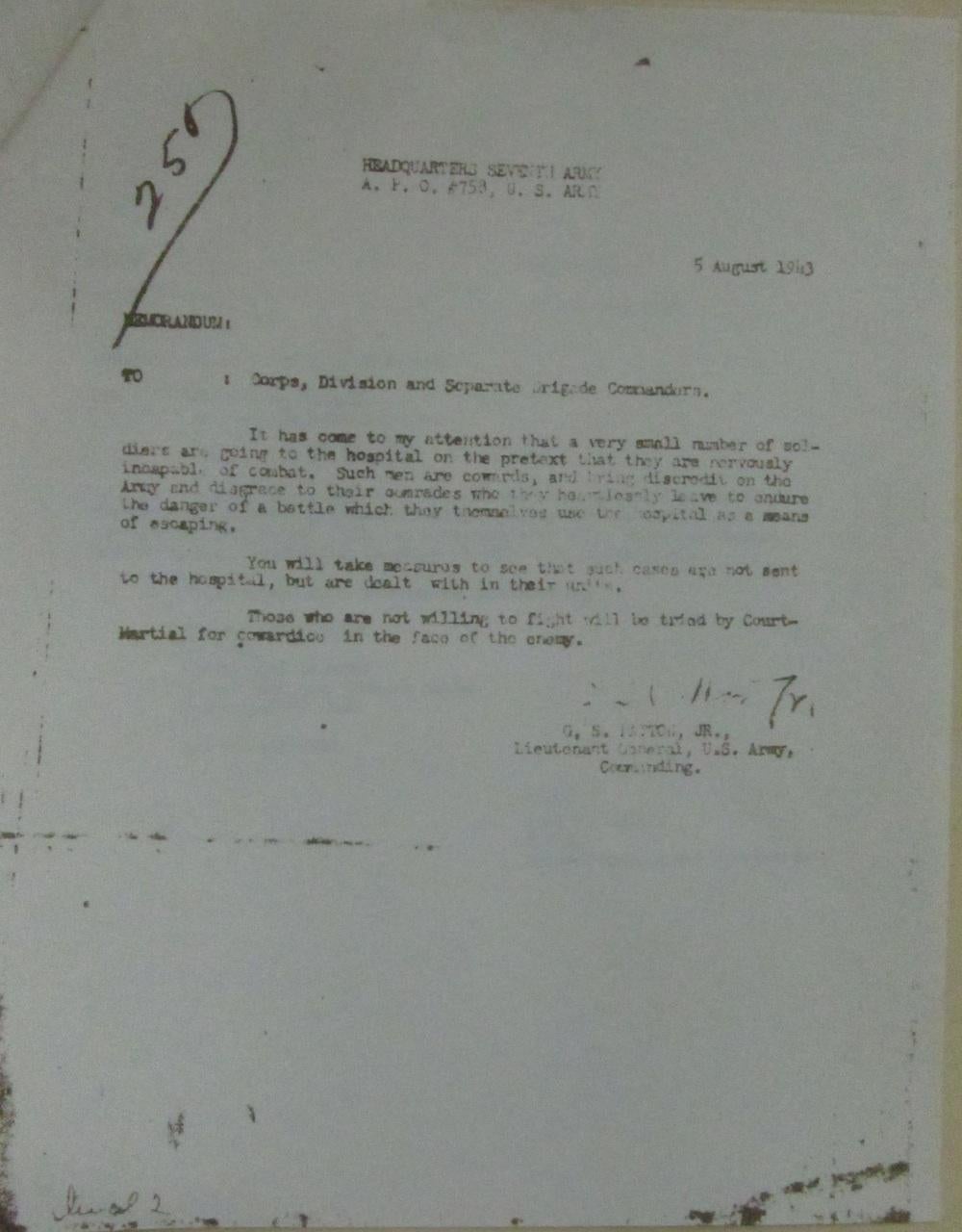

A number of U.S. military officers doubted the legitimacy of mental casualties during World War II. Some presumed that soldiers who claimed to have suffered nervous breakdowns on the battlefield were malingering to avoid serving in harm’s way. Nothing reflected that attitude more than this order from Gen. George S. Patton to all commanders in the Seventh Army, then stationed in Italy, on Aug. 5, 1943.

“It has come to my attention that a very small number of soldiers are going to the hospital on the pretext that they are nervously incapable of combat,” wrote Patton. “Such men are cowards, and bring discredit on the Army and disgrace to their comrades who they heartlessly leave to endure the danger of a battle which they themselves use the hospital as a means of escaping.”

The order came two days after Patton slapped a private named Charles Kuhl who was being treated for “moderately severe” anxiety at an evacuation hospital in Sicily. A week later, at another hospital, Patton slapped another private, Paul Bennett, who was also recovering from a breakdown. Patton demanded that Bennett return to the front lines and drew his sidearm to show he meant it.

By the middle of 1943, mental breakdowns made up 15 to 25 percent of all battle casualties in many campaigns. At the time of Patton’s order, the Army was discharging 115,000 soldiers a year for psychiatric reasons. That trend began to turn later that year, when the military ordered psychiatrists to join infantry divisions in combat and treat mental casualties at the front lines.

As for Patton, the American public was split over his actions. Some were outraged by his brash behavior and mindset; others believed it was necessary to win the war. The controversy delayed the confirmation of his promotion to the permanent rank of major general, and earned him censure from Gen. Eisenhower. Patton did issue a formal apology, but still felt the best medicine for “mental anguish” was tough love.

Parts of this post have been adapted from A Curious Madness: An American Combat Psychiatrist, a Japanese War Crimes Suspect, and an Unsolved Mystery from World War II.

National Archives.

Correction, Jan. 16, 2014: Due to an editing error, this post originally anachronistically described Eisenhower as “president”—a position he would not attain until 1953.

Update, Jan. 16, 2014: This post has been updated to clarify the nature of Patton’s delayed promotion at the end of 1943. Due to wartime circumstances, Patton was temporarily acting as a lieutenant general, while his permanent rank was that of colonel. The September 1943 promotion that was held up in the Senate due to the slapping incidents was a two-rank jump, to the permanent rank of major general.