The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

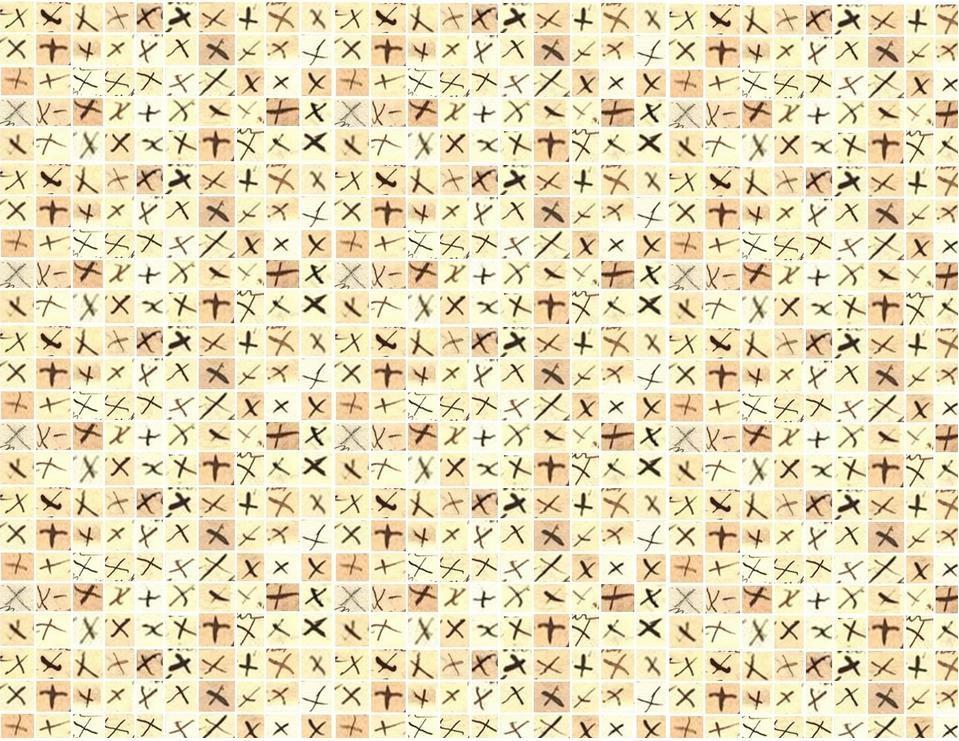

This grid of tiny Xs is made up of the signatures of slaves who petitioned for their freedom in the courts of St. Louis during the time between Missouri’s statehood (1821) and the Dred Scott decision (1857). Some of these plaintiffs—like Solomon Northup, the historical figure whose story is the basis of the film 12 Years a Slave—were formerly free men who were victims of kidnapping. All of them showed great bravery in resisting their enslavement publicly.

University of Iowa law professor Lea VanderVelde worked with a set of around 300 antebellum civil cases from the courts in St. Louis while writing her forthcoming book, Redemption Songs: Courtroom Stories of Slavery. Some petitions that VanderVelde reviewed based the slaves’ claim to freedom on their previous status, while others argued that they had resided in a free state (usually Illinois) with their masters and were therefore legally free.

VanderVelde thinks that enslaved people in St. Louis, particularly women who worked as laundresses alongside free black counterparts, probably heard about the option to sue for freedom through word of mouth. In this urban setting, slaves had a certain degree of mobility, conferred so that they could pursue their masters’ errands. Often, VanderVelde says, they would slip away to the courthouse or to a justice of the peace to file.

You might expect that these petitioners would have little luck in a white court system operating in a slave state. But the plaintiffs were assigned attorneys if they couldn’t afford their own—an unusual practice at the time—and a fair number succeeded in convincing the all-white juries that the rule of law demanded a favorable verdict. (VanderVelde estimates that around a third of the cases that she examined ended in success for the petitioners.)

In one such story, Lydia Titus, a free resident of Illinois, sued on behalf of her family. Titus was asleep at her homestead with her six grown children when three white men arrived in the middle of the night, claimed ownership over the younger Tituses, and took them to St. Louis. Titus—“a resourceful woman,” VanderVelde says—guessed at their destination, followed the group to St. Louis, and helped them file for their freedom. She eventually won, but three of her children died while in the limbo of imprisonment.

Image courtesy Lea VanderVelde.

Clarification, Monday, October 21, 2:31 PM: The image below is of 51 signatures, some of which are repeated. Altogether, VanderVelde collected around 170 images of “x” signatures; in the remaining cases, the signature page was lost, or the plaintiff’s lawyer signed in place of their client.