The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

These jokes come from 1910s-era issues of Boys’ Life, the Boy Scouts of America’s official magazine, which is available in fully scanned form via Google Books. The magazine was founded in 1911, a year after the BSA itself.

In the 1910s, Boys’ Life ran a mix of adventure stories; pep talks from prominent men within the organization; advice on running Scout troops (there was a lot of confusion regarding procedure in those first few years); and columns about nature, wireless radio, and electricity.

The section these jokes came from was called “Think and Grin” and featured a mix of riddles, jokes, and miniature brain-teasers. (Here’s a sample “Think and Grin,” so you can see the jokes in context.) Often, the writer would solicit contributions directly from Scouts, offering small prizes for winners.

These little bits of humor are often as groaningly awful as the jokes kids like today. But in their subject matter and their approach, they are striking reminders of how much things have changed in the intervening century.

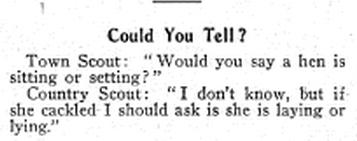

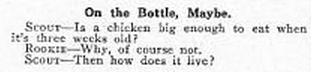

Many “Think and Grin” jokes rely on knowledge of farm life for their humor. There are a large number of chicken jokes, some of which will likely be lost on 21st-century readers.

Boys’ Life, August 1913.

Boys’ Life, December 1916.

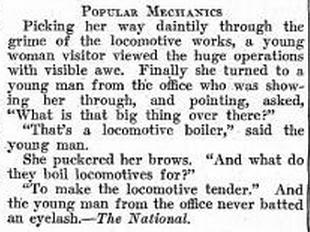

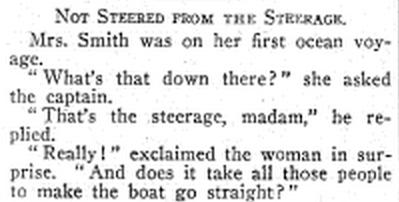

If Scouts were familiar with farming, they were also expected to be comfortable with technology and science. Often jokes rested on the difference between a Scout “in the know” and a person ignorant by contrast. In a common scenario, a lady or a girl would come into contact with technology and react in complete bewilderment.

Boys’ Life, June 1916.

Boys’ Life, August 1914.

Uneducated immigrants didn’t fare much better, when it came to understanding science. (“Begorra” was an Irish exclamation.)

Boys’ Life, April 1917.

But maybe everyone—especially everyone who was old—had trouble with new technologies.

Boys’ Life, August 1916.

Corporal punishment, once far more common and accepted in the United States, was so normal at the time as to form the basis for humor.

Boys’ Life, March 1919.

I may be misinterpreting this one, but I think it’s fairly bawdy, for the Boy Scouts.

Boys’ Life, January 1918.

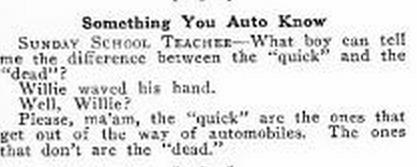

Some jokes contained little lessons for Scouts, in safety or conduct. (During the first few decades of the automobile era, many children were killed by cars while playing in the streets.)

Boys’ Life, August 1917.

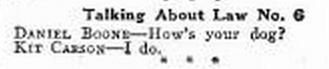

Scout Law No. 6 is the injunction to “Be Kind,” even to animals. The pun here is groanworthy; the reason for using “Daniel Boone” and “Kit Carson,” unclear.

Boys’ Life, October 1916.

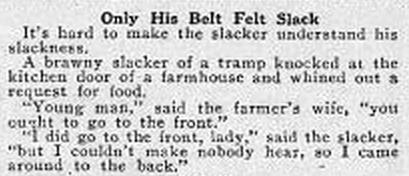

Topical humor about World War I poked fun at “slackers” who refused to do their duty.

Boys’ Life, October 1918.

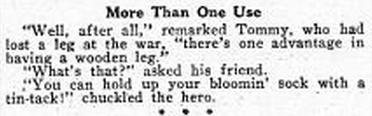

And made hay out of tragedy.

Boys’ Life, June 1918.

The casual racial stereotypes of mainstream American culture reached into the pages of Boys’ Life. There are more than a few examples of stereotype-heavy humor about African-Americans. (Here’s one, another, and another.)

The Irish, who were, as historian Noel Ignatiev would put it, not quite yet “white,” were the brunt of many a Scout jest:

Boys’ Life, August 1914.

Boys’ Life, February 1917.