The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

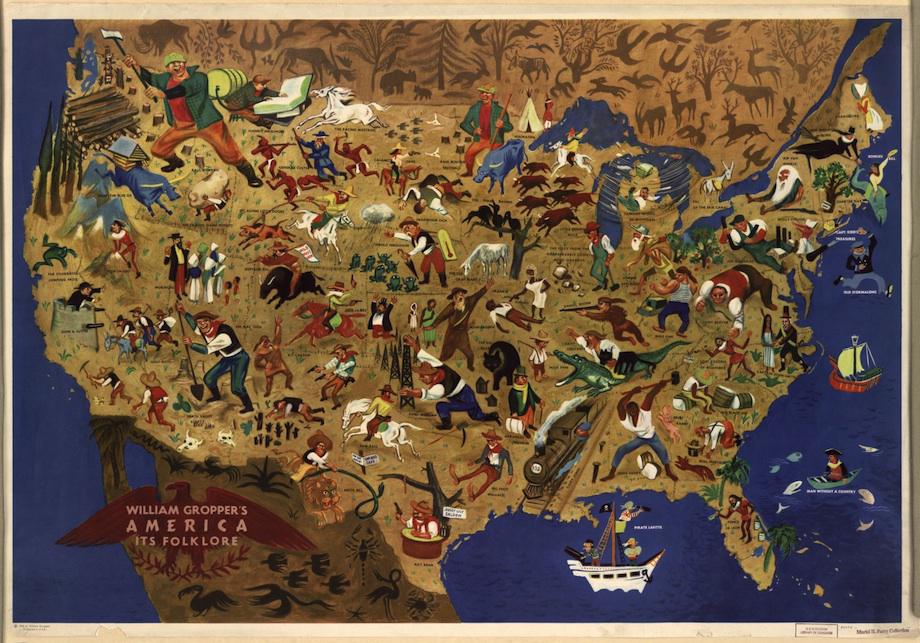

This map, by social realist artist William Gropper, was created to showcase the diversity of national myths and folk stories and was distributed abroad through the U.S. Department of State starting in 1946. (You can see it up close by clicking on the image below to arrive at a zoomable version, or by navigating to the map’s page on the website of the Library of Congress.)

Gropper, born in New York City’s Lower East Side to a working-class family, deeply identified with labor movements and the Left throughout his life. He worked as a cartoonist for mainstream publications New York Tribune and Vanity Fair, as well as the leftist and radical newspapers Rebel Worker, New Masses, and Daily Worker. During the Depression, like many other out-of-work artists, Gropper designed murals for the Works Progress Administration.

The “folklore” on display in this richly illustrated map is a soup of history, music, myth, and literature. Frankie and Johnny are cheek-by-jowl with a wild-eyed John Brown; General Custer coexists with “Git Along Little Dogies.” Utah is simply host to a group of “Mormons,” in which a bearded man holds up stigmata-marked hands to a small group of wives and children, while a figure labeled “New England Witches” flies over New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Vermont.

So many of these stories are now unfamiliar that the map makes an excellent portal for investigation. I’m from New England but had to look up the origin of “Evangeline” (the figure that decorates Maine). Turns out, the name is a reference to a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem about the expulsion of Acadian inhabitants from Nova Scotia in the 18th century. (An early 20th-century book and a 1929 movie adaptation had likely kept the Evangeline myth fresh in Gropper’s mind.)

The presence of this map in American information offices overseas provoked Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s suspicions. As Gropper’s biographer Louis Lozowick writes, the 1953 summons to testify for the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations about the map was quite ironic, given that its content was anything but subversive. McCarthy simply didn’t like Gropper’s past associations. Gropper pled the Fifth and refused to testify for McCarthy—a stance that lost him many commissions.

I first saw this map on library science professor Carol Tilley’s Twitter feed.

“William Gropper’s America, Its Folklore,” New York: Associated American Artists, c1946. Library of Congress. Click on the image to arrive at a zoomable version.

See more of Slate’s maps.