The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

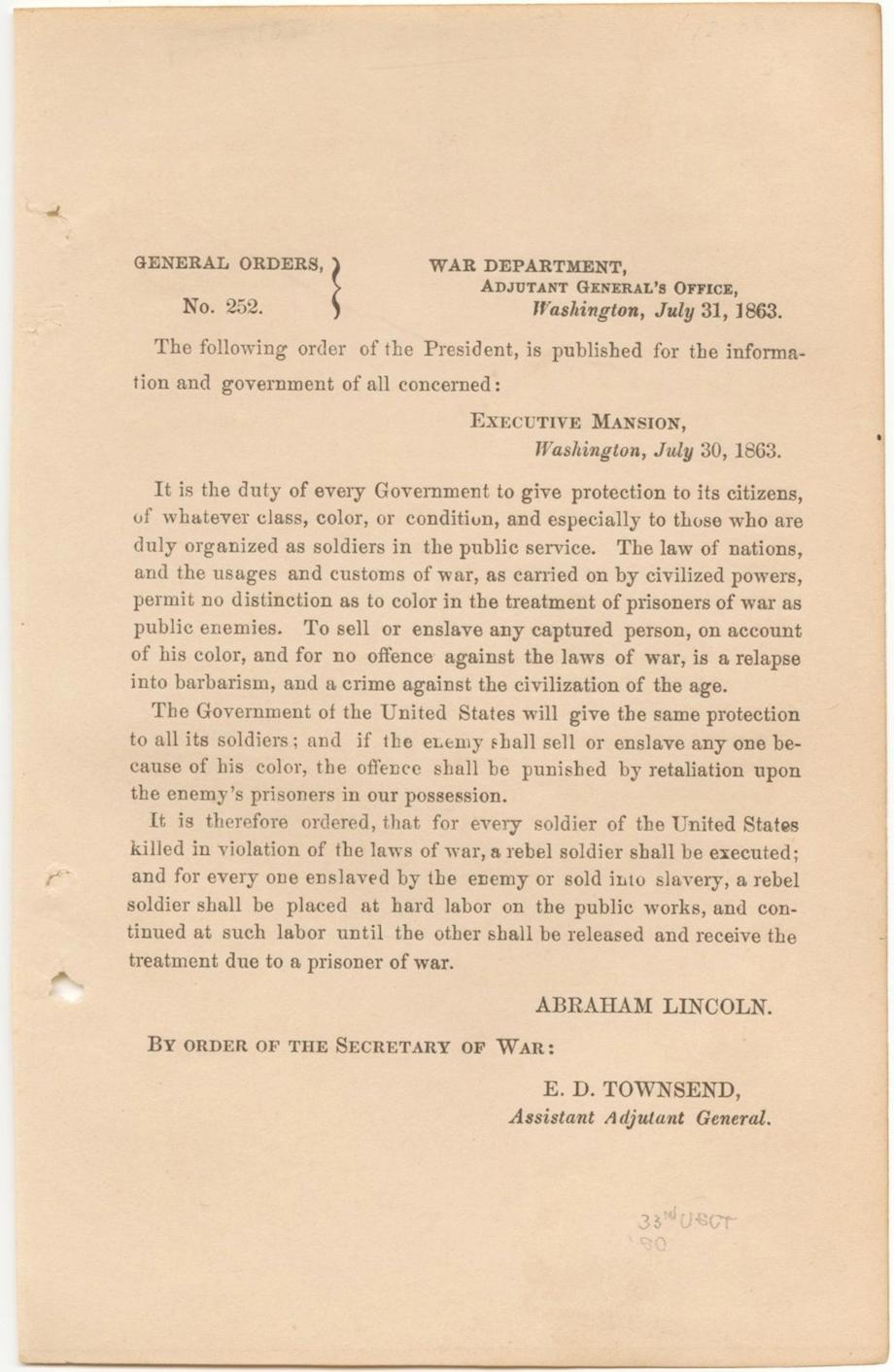

In his General Order No. 252, issued on July 31, 1863, Abraham Lincoln made a promise he had to have known he could not fully keep. Upset at news that black Union soldiers, when taken prisoner by Confederates, had been treated differently from white POWs, Lincoln ordered that any indignities visited upon black troops would be replicated on an equal number of Confederate POWs.

“For every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a rebel soldier shall be executed,” Lincoln wrote. “For every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works, and continued at such labor until the other shall be released and receive the treatment due to a prisoner of war.”

Black Union soldiers faced harsh consequences when captured as POWs, with Confederate policy initially holding that they could be tried as criminal insurrectionists in state courts, and executed as such. The Confederate Congress also threatened to enslave black POWs—even those who had lived as free men in the North before the war.

Often, however, threats to black soldiers were more immediate. Black POWs were abused, forced to labor in the line of fire, and shot after surrendering or while “trying to escape.”

While the concept of eye-for-an-eye punishment might seem medieval, during the Civil War the practice of retaliatory killing was not uncommon. Historian Lonnie Speer has argued that black and white POWs throughout the Civil War were punished or killed to even a score—and this occurred with the knowledge and involvement of military leaders.

Despite this precedent, and continuing unequal treatment of black POWs, Lincoln found it politically and logistically impossible to follow his own orders to the letter.

In some instances, however, he was able to stand by his position that black prisoners be treated the same as white ones. For example, he insisted that black soldiers should be considered equal to whites in POW exchanges—a policy the Confederates finally agreed to in January 1865.

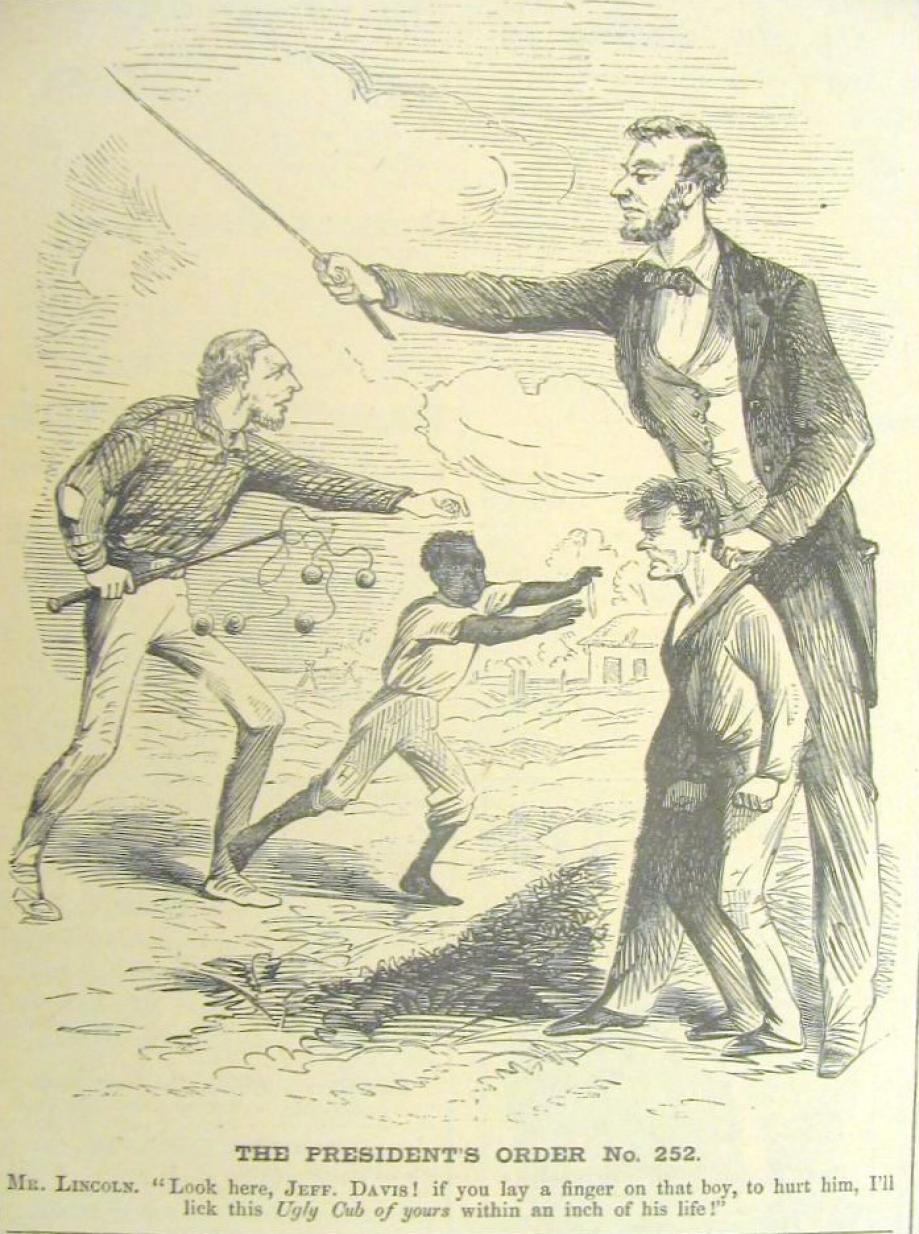

The Harper’s cartoon below the order, depicting Lincoln and Jefferson Davis as paternal figures threatening to whip recalcitrant boys, lampooned the news of the order a few weeks after it was given.

Cornell University Library, Rare and Manuscript Collections Images.

Harper’s Weekly, August 15, 1863. Via The McCune Collection.