The Vault is Slate’s history blog. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter @slatevault, and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

In a 1913 article, a portion of which is reprinted below, Sylvia Pankhurst, the British suffragette, describes the experience of being force-fed in prison. Like the rapper, actor, and activist Yasiin Bey (formerly Mos Def), who subjected himself to force-feeding last week in order to draw attention to the experiences of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, Pankhurst used a first-person description of the procedure to show its brutality.

Pankhurst, whose mother Emmeline and sister Christabel were also prominent suffragettes, went to jail multiple times in 1913 alone, trying to draw attention to her cause. In 2005, the British government released documents that showed how careful those in charge of her case were to prevent her from dying in prison, as they were aware of her power as a political symbol.

One of these documents shows that a physician was sent to the prison to assess the procedure and returned with a recommendation that its use be discontinued in Pankhurst’s case. He blamed her own behavior for her pain:

I wish it be understood that it is not the actual feeding which is endangering her but the mental excitement which she works herself into before during and after each feed, together with the strenuous resistance she always offers.

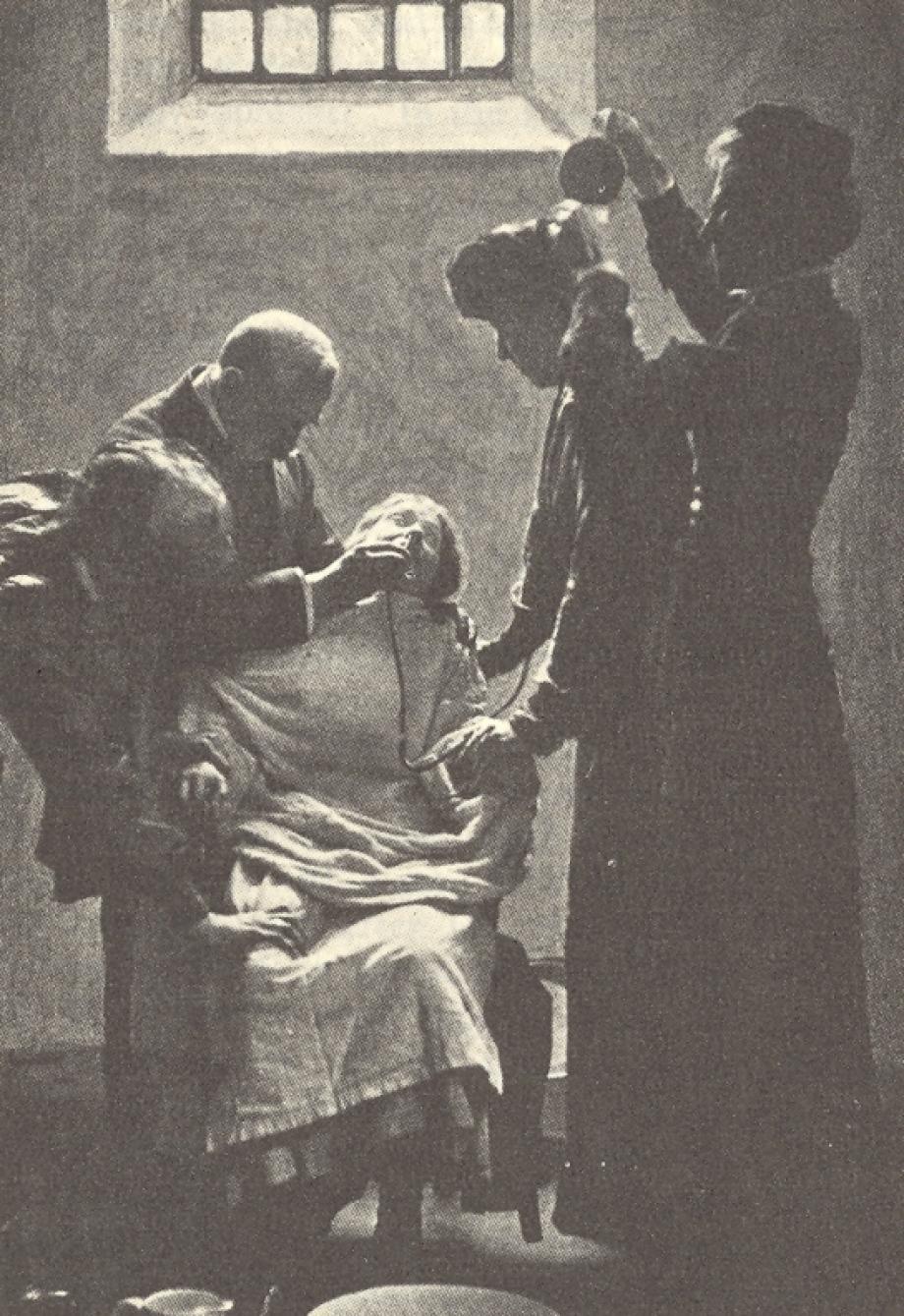

The British press covered the issue of force-feeding extensively. To satisfy the public’s curiosity, papers such as the Illustrated London News commissioned artists to create imagined representations of what the procedure might look like (as in the image that accompanies this post).

The version of Pankhurst’s story that appears below was printed in McClure’s magazine, an American literary and current-events periodical of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Manchester Guardian printed an earlier, briefer version of Pankhurst’s account on March 26, 1913.

This article was brought to my attention by the editors of the new project The Browser Review, a site that resurrects and reprints news stories from 100 years ago.

Artist’s impression of a prisoner being force-fed. Published in the Illustrated London News, April 27, 1912. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

FORCIBLY FED: THE STORY OF MY FOUR WEEKS IN HOLLOWAY GAOL

by E. Sylvia Pankhurst

As published in McClure’s magazine, August 1913, pp 87-93. This is an excerpt. The entire piece may be found here.

… About half past nine that first morning, the doctor came to me and saw the breakfast tea and bread and butter lying untouched. He pointed to it and said: “Will you not reconsider?” I answered, “No”. Then he felt my pulse and sounded my heart, and went away.

At twelve o’clock a wardress brought me a chop, some potatoes and cabbage, and some milk pudding. At five came supper—bread, butter, an egg, and a pint of milk. I left them all untasted, and sat reading the Bible hour after hour. I had nothing else to do.

So two days passed. I felt constantly a little hungry, but never for one moment did I wish to eat a morsel. I was very cold—partly, I suppose, from want of food, partly because the temperature of the cell was very low, the hot water pipe—the only means of heating—having little warmth in it. I sat with my feet on the hot-water pipe, wearing a woollen dress, a thick knitted woollen sweater, a long cloth coat, and with thick woollen gloves on my hands; but still I was cold.

On the morning of the third day I was taken out into the corridor to be weighed, and some time afterwards the two doctors came into my cell to sound my heart again. They said: “Will you eat your food?” And—when I said, “No”,—“Then we have only one alternative—to feed by force.”

They went. I was trembling with agitation, feverish with fear and horror, determined to fight with all my strength and to prevent by some means this outrage of forcible feeding. I did not know what to do. Ideas flashed through my mind, but none seemed of any use.

I gathered together in a little clothes basket my walking-shoes, the prison brush and comb and other things, and put them beside me, where I stood under the window, with my back to the wall.

I thought that I would throw these things at the doctors if they dared to enter my cell to torture me. But, when the door opened, six women officers appeared, and I had not the heart to throw things at them, though I struck one of them slightly as they all seized me at once.

I struggled as hard as I could, but they were six and each one of them much bigger and stronger than I. They soon had me on the bed and firmly held down by the shoulders, the arms, the knees, and the ankles.

Then the doctors came stealing in behind. Some one seized me by the head and thrust a sheet under my chin. I felt a man’s hands trying to force my mouth open. I set my teeth and tightened my lips over them with all my strength. My breath was coming so quickly that I felt as if I should suffocate. I felt his fingers trying to press my lips apart,—getting inside,—and I felt them and a steel gag running around my gums and feeling for gaps in my teeth.

I felt I should go mad; I felt like a poor wild thing caught in a steel trap. I was tugging at my head to get it free. There were two of them holding it. There were two of them wrenching at my mouth. My breath was coming faster and with a sort of low scream that was getting louder. I heard them talking: “Here is a gap.”

“No; here is a better one—this long gap here.”

Then I felt a steel instrument pressing against my gums, cutting into the flesh, forcing its way in. Then it gradually prised my jaws apart as they turned a screw. It felt like having my teeth drawn; but I resisted—I resisted. I held my poor bleeding gums down on the steel with all my strength. Soon they were trying to force the india-rubber tube down my throat.

I was struggling wildly, trying to tighten the muscles and to keep my throat closed up. They got the tube down, I suppose, though I was unconscious of anything but a mad revolt of struggling, for at last I heard them say, “That’s all”; and I vomited as the tube came up.

They left me on the bed exhausted, gasping for breath and sobbing convulsively. The same thing happened in the evening; but I was too tired to fight so long.

Day after day, morning and evening, came the same struggle. My mouth got more and more hurt; my gums, where they prised them open, were always bleeding, and other parts of my mouth got pinched and bruised.

Often I had a wild longing to scream, and after they had gone I used to cry terribly with uncontrollable noisy sobs; and sometimes I heard myself, as if it were some one else, saying things over and over again in a strange, high voice.

Sometimes—but not often; I was generally too much agitated by then — I felt the tube go right down into the stomach. It was a sickening sensation. Once, when the tube had seemed to hurt my chest as it was being withdrawn, there was a sense of oppression there all the evening after, and as I was going to bed I fainted twice. My shoulders and back ached very much during the night after the first day’s forcible feeding, and often afterwards.

But infinitely worse than any pain was the sense of degradation, the sense that the very fight that one made against the repeated outrage was shattering one’s nerves and breaking down one’s self-control.

Added to this was the growing unhappy realization that those other human beings, by whom one was tortured, were playing their parts under compulsion and fear of dismissal, that they came to this task with loathing of it and with pity for their victim, and that many of them understood and sympathised with the fight the victim made.