The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

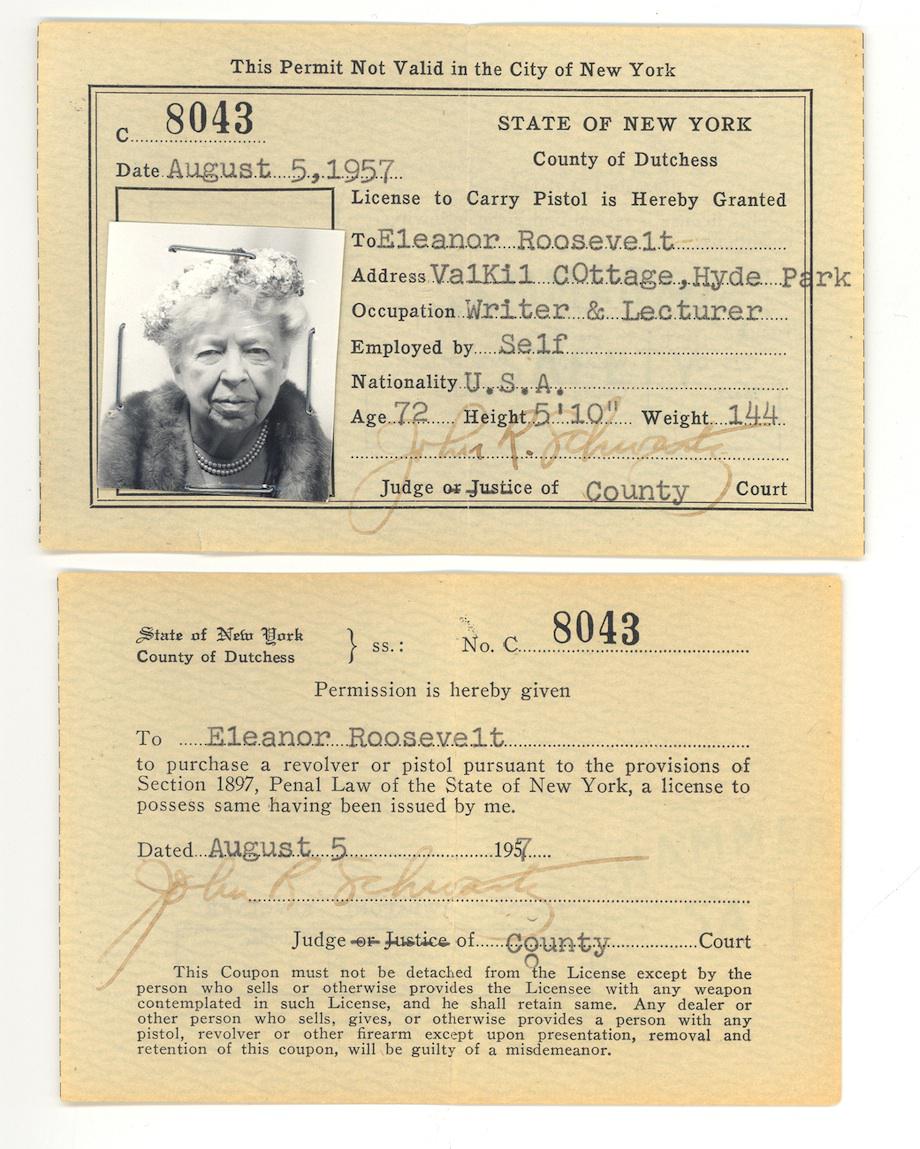

At the FDR Library, one exhibit holds the contents of Eleanor Roosevelt’s wallet. While many of the cards and slips of paper from the wallet are fascinating (a Met membership card, a scrap of a poem about the importance of good cooks), this pistol permit is perhaps the most surprising.

Roosevelt was a peripatetic traveler, covering large distances in service of the many projects she pursued both during and after the FDR presidency. It was Eleanor’s determination to drive her own car that led to her pistol ownership. The Secret Service begged her to take an agent, a police escort, or at least a chauffeur; she refused. The pistol was a compromise: a small bit of protection to put their minds at ease.

The argument that women should carry weapons to protect themselves wasn’t a common one during the 1930s and 1940s. Laura Browder, author of Her Best Shot: Women and Guns in America, writes on her website that while early twentieth-century ads selling guns to women touted firearms ownership for personal safety, the theme vanished during the midcentury (and re-emerged again in the 1980s). Eleanor’s situation, as a stubbornly independent First Lady, was clearly an unusual one.

Although Eleanor told the fascinated press, when she first got the weapon, that she was a “fairly good shot,” a New York Times reporter at the 1972 dedication of the Eleanor Roosevelt Wings of the FDR Library interviewed several of Eleanor’s friends who said that she carried the permit, but not the pistol.

Image courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.