The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

As a U.S. Marine Corps fighter pilot serving in the Pacific during World War II, 2nd Lt. Sam Folsom received several blood chits, or rescue patches, to assist him if he found himself behind enemy lines. The chits, or official IOUs from the U.S. government, requested help for a stranded airman and promised a reward for those who came to his aid. Usually written in various languages, depending on where the pilots operated, the chits were often sewn on flight jackets or issued as letters or cards.

Though the British regularly used blood chits during World War I, they were first issued by the United States military in China during World War II and were eventually employed in all theaters of the war. The amount awarded for authenticated claims, which numbered in the tens of thousands, ranged from $50 to $250, depending on the theater.

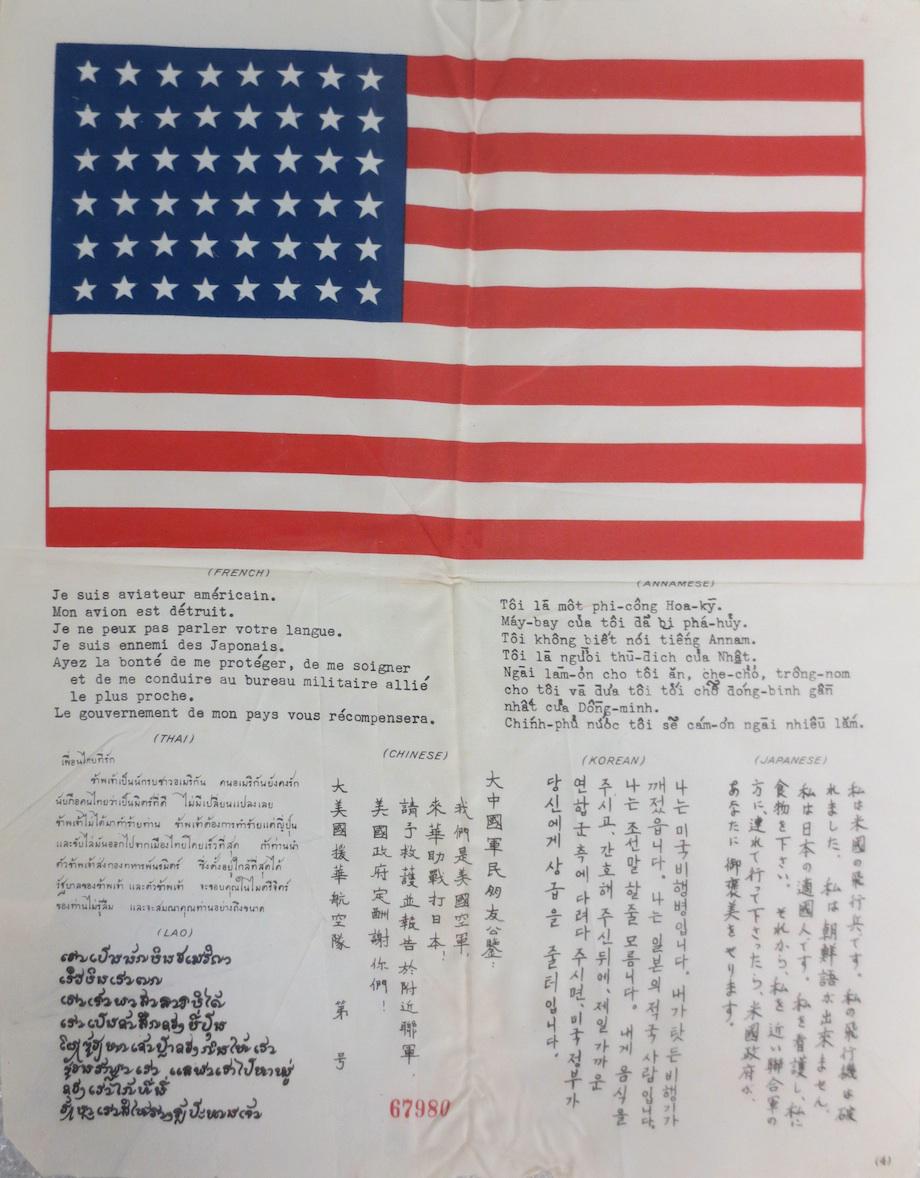

This blood chit, issued to Folsom while he served with the Marine Fighting Squadron 121 (VMF 121), is made of silk and measures 8 1/8 x 12 inches. Written in French, Vietnamese, Thai, Lao, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese and topped by an American flag, the message describes the flyer’s predicament (“I am an American aviator. My plane is destroyed. I do not speak your language”), establishes his loyalty (“I am an enemy of the Japanese”), and appeals to the reader’s mercy while offering worldly rewards (“Have the kindness to protect me, to care for me and to take me to the nearest allied military office. My government will pay you.”)

Folsom, who was fortunate to never need to use a blood chit during the war, remained with the Marine Corps until he retired in 1960 as a lieutenant colonel. Now almost 93 years old, Folsom volunteers at New York City’s Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum, where he donated four blood chits, along with his other war memorabilia.

The U.S. military continued to use blood chits during the Korean and Vietnam wars. Today, details about the program are classified, due to possible danger to those who assist U.S. service members.

Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum, Gift of Sam Folsom, Lt. Col. USMC.