The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

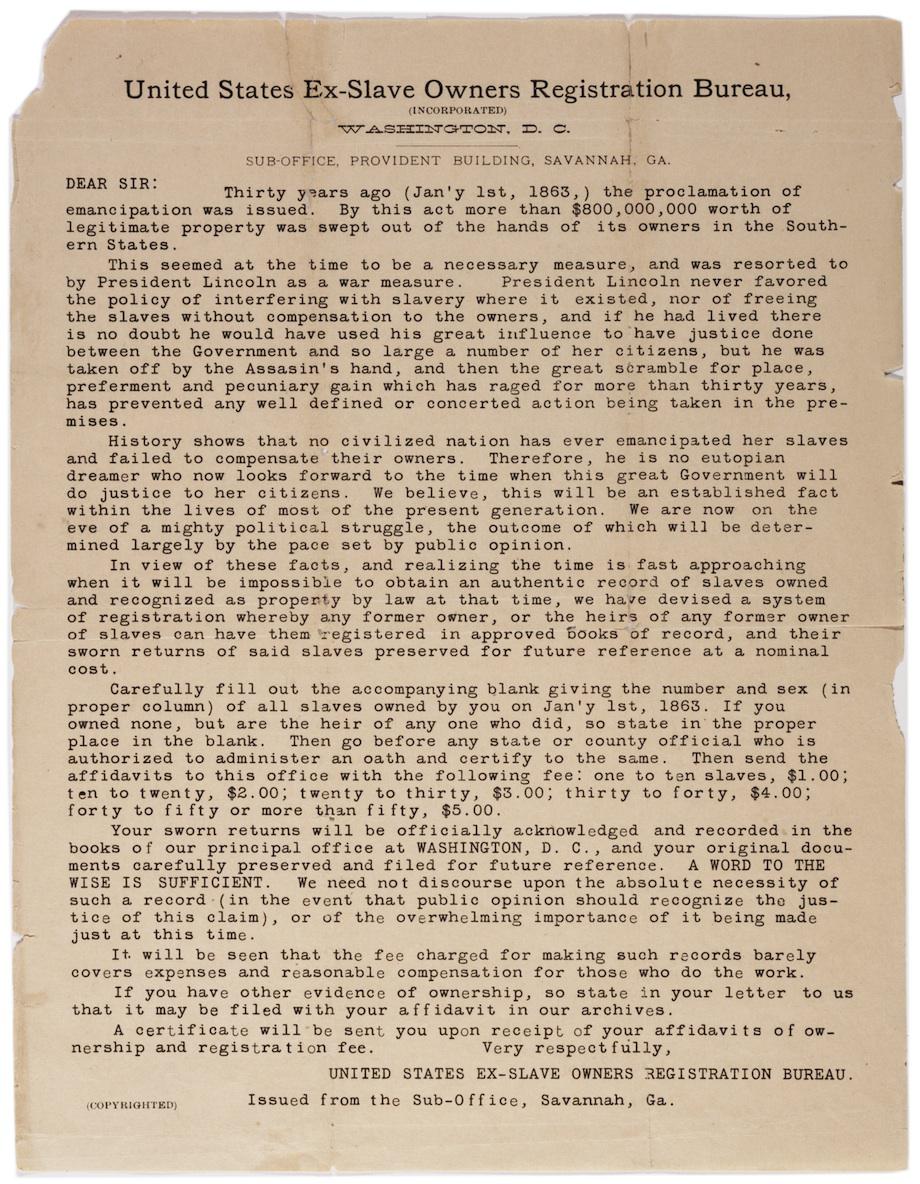

This broadside, from a business calling itself the United States Ex-Slave Owners Registration Bureau, was sent to select Southerners in 1893.

Noting, in outrage, that the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation had “swept” “more than $800,000,000 worth of legitimate property…out of the hands of its owners in the Southern States,” the anonymous author asked readers to send him names of their slaves, evidence of ownership, and a small fee for the services of the registry. The Bureau promised to keep these records safe, until the time when “public opinion” might “recognize the justice of this claim.” After all, the author argued, “no civilized nation has ever emancipated her slaves and failed to compensate their owners.”

The example foremost in readers’ minds must have been that of Britain, which awarded its slaveowners 20 million pounds in taxpayers’ money when it abolished slavery in 1833.

As for the broadside’s claim that President Lincoln might have made sure the owners had been compensated had he lived, it seems that the author is referring to evidence such as the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, signed by Lincoln in 1862, which gave slaveowners in DC $300 for each slave.

Although Lincoln did propose to extend a similar scheme to other states before finally signing the Emancipation Proclamation, it appears that the proposed compensation was a matter of expedience, rather than principle. It’s by no means clear that Lincoln intended to compensate slaveowners retroactively after the end of the war.

It turns out that this document was part of a fraud meant to extract money from bitter Southerners eager for compensation. The Washington, DC National Tribune, a newspaper for Civil War veterans on the Union side, wrote (indulging in its own flavor of racism) that a “smart individual of Hebrew extraction” had set up the scheme.

Pointing out that the “scheme” was not signed by anybody in particular, and that it was unendorsed by “any well-known man,” the newspaper wondered how “anybody should be such a fool as to pay money to such a manifest fraud.” Nonetheless, the Tribune reported, “the cunning schemer harvested dollars quite plentifully until the Postmaster-General closed the mails to him.”

GLC09019 United States Ex-Slave Owners Registration Bureau, [Reconstruction broadside], 1893. (Courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.)