The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

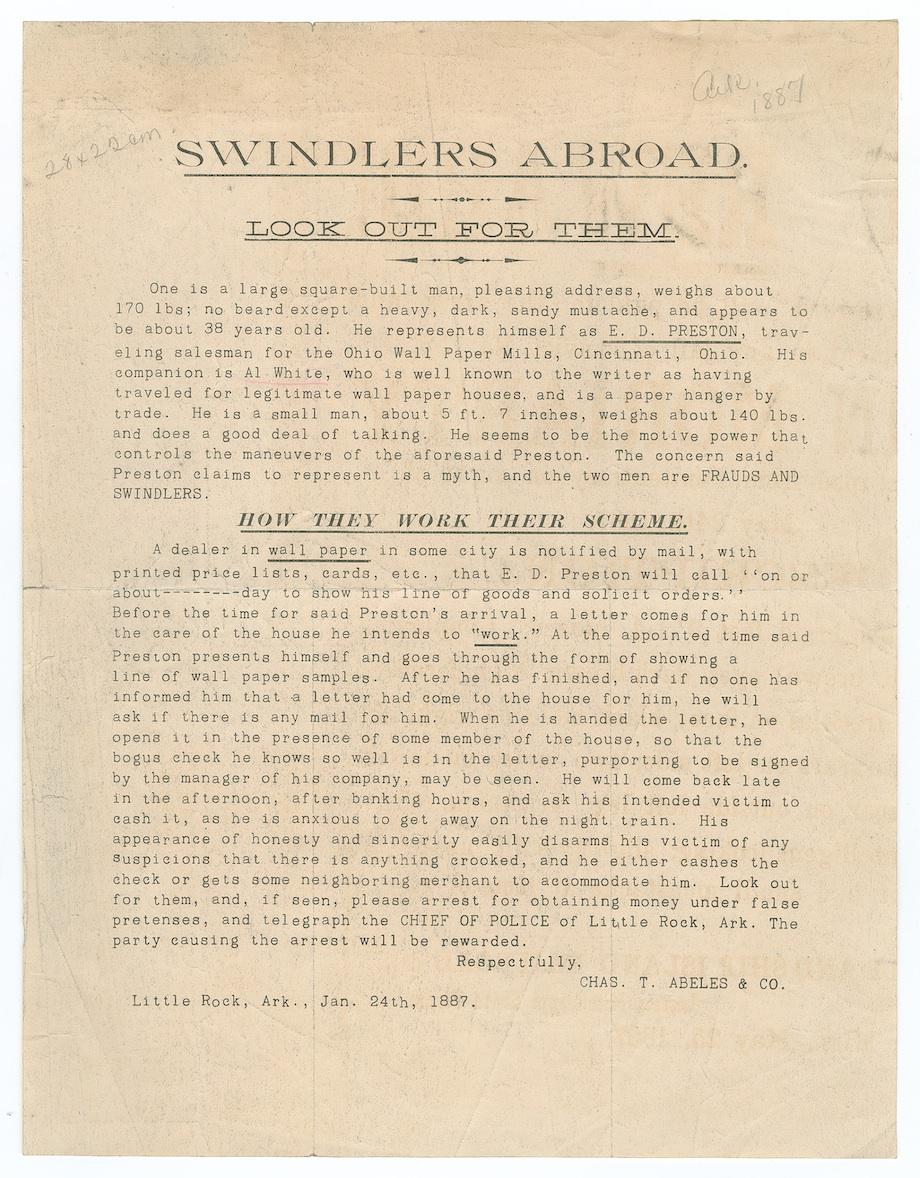

This broadside, which dates to 1887, was written by a Little Rock, Ark., businessman who had fallen prey to two con men. The sheet describes a swindle that took advantage of trust and professional courtesy. The swindlers, having established themselves as traveling salesmen for a wallpaper factory in Ohio, gained access to the Charles T. Abeles Company under those pretenses. (The company, established in 1880, made doors and interior trim from “famous Arkansas soft pine” and also manufactured and sold paints, glass, wallpaper, and other supplies necessary for finishing new dwellings.) Having faked their way through showing their samples, the men asked if the business would do the favor of cashing a check. Thus enriched, the swindlers hopped the next train, never to be seen again.

Amy Reading, historian and author of The Mark Inside: A Perfect Swindle, a Cunning Revenge, and a Small History of the Big Con, says that swindles like these were “extremely common” in the late 19th century, in a country where railroad track was spreading more quickly than informal networks of trust. “There wasn’t even a national bank until 1863, and so interpersonal methods of cashing checks were far more common back then,” Reading says. “The methods of doing business still relied on local and time-worn byways of authority, even as goods and people poured into towns like Little Rock from afar.”

Nor was it uncommon for a mark, having fallen for a con, to try to bring perpetrators to justice. “There is a truism among con men that a sucker never squeals, and like most things that con men say, it isn’t true at all,” Reading says. Marks would often seek police help or try to out con men in newspapers—usually to no avail.

Reading thinks that marks, who often wrote detailed descriptions of their swindles like this one, seemed to be trying to regain a measure of self-respect by recounting what happened: “It’s as if a precise explanation of the swindle, with as few passionate or emotional words as possible, will demonstrate that the mark really is a rational businessman who never deserved what he got.”