The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

In the disastrous LL Cool J/Brad Paisley collaboration “Accidental Racist,” Paisley sort-of excuses his Confederate flag T-shirt by saying that he’s just a really big fan of Lynyrd Skynyrd.* (This despite the fact that, as Jezebel’s Dodai Stewart points out, Skynyrd’s members have distanced themselves from that toxic symbol in recent years.)

Paisley’s misguided effort also harks back to an older type of song about the South: the sheet music published in the decades after the Civil War. In an age before widespread availability of recorded music, people bought these booklets to use at home or with friends.

“Dixie” pride featured prominently in many of these sentimental songs. Like Paisley’s, the songs offered surface reconciliation while smoothing over real historical conflicts.

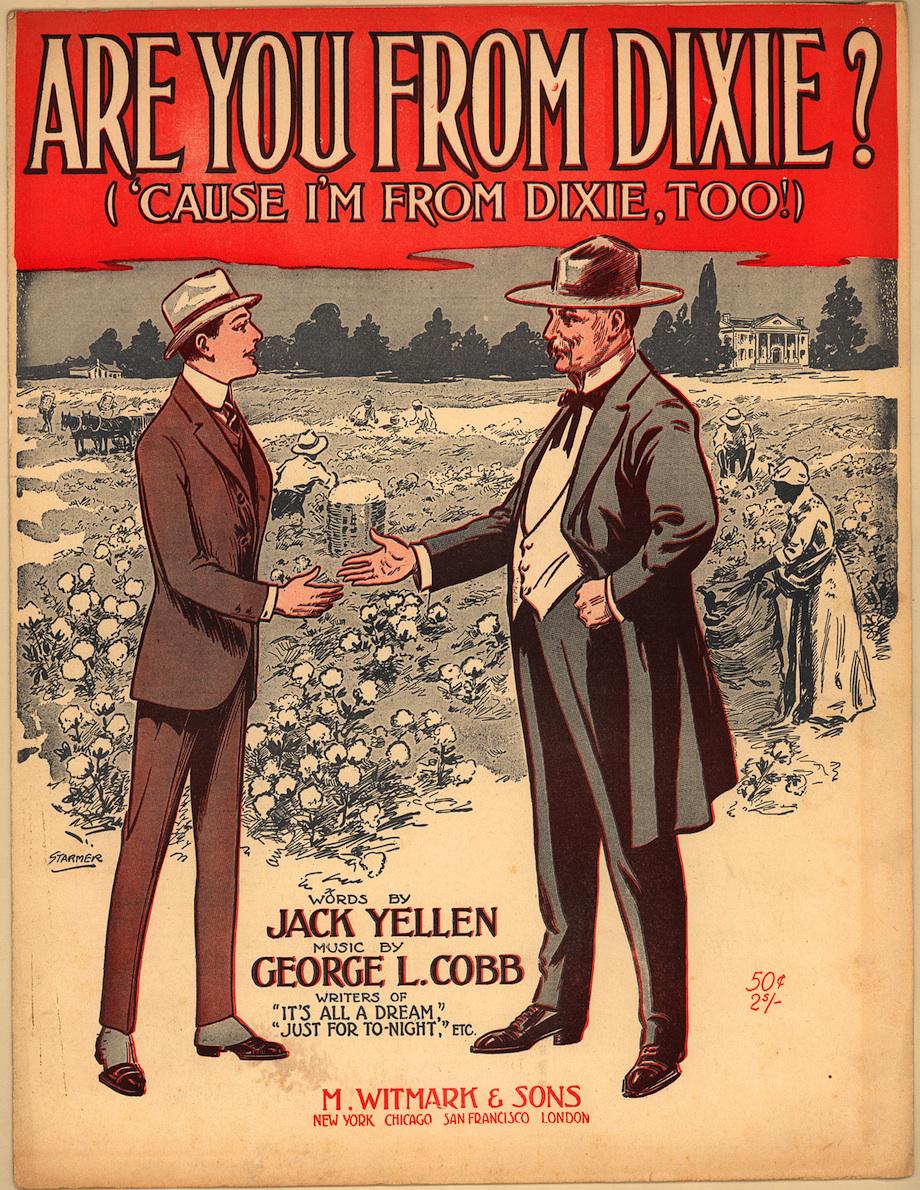

The song “Are You From Dixie? (’Cause I’m From Dixie, Too!)” was written from the point of view of an expatriate white Southerner who recognizes a fellow countryman. The illustration on the front of the booklet features two white men shaking hands with a cotton field full of black workers in the background—making it clear that being “from Dixie” meant a memory of plantation days.

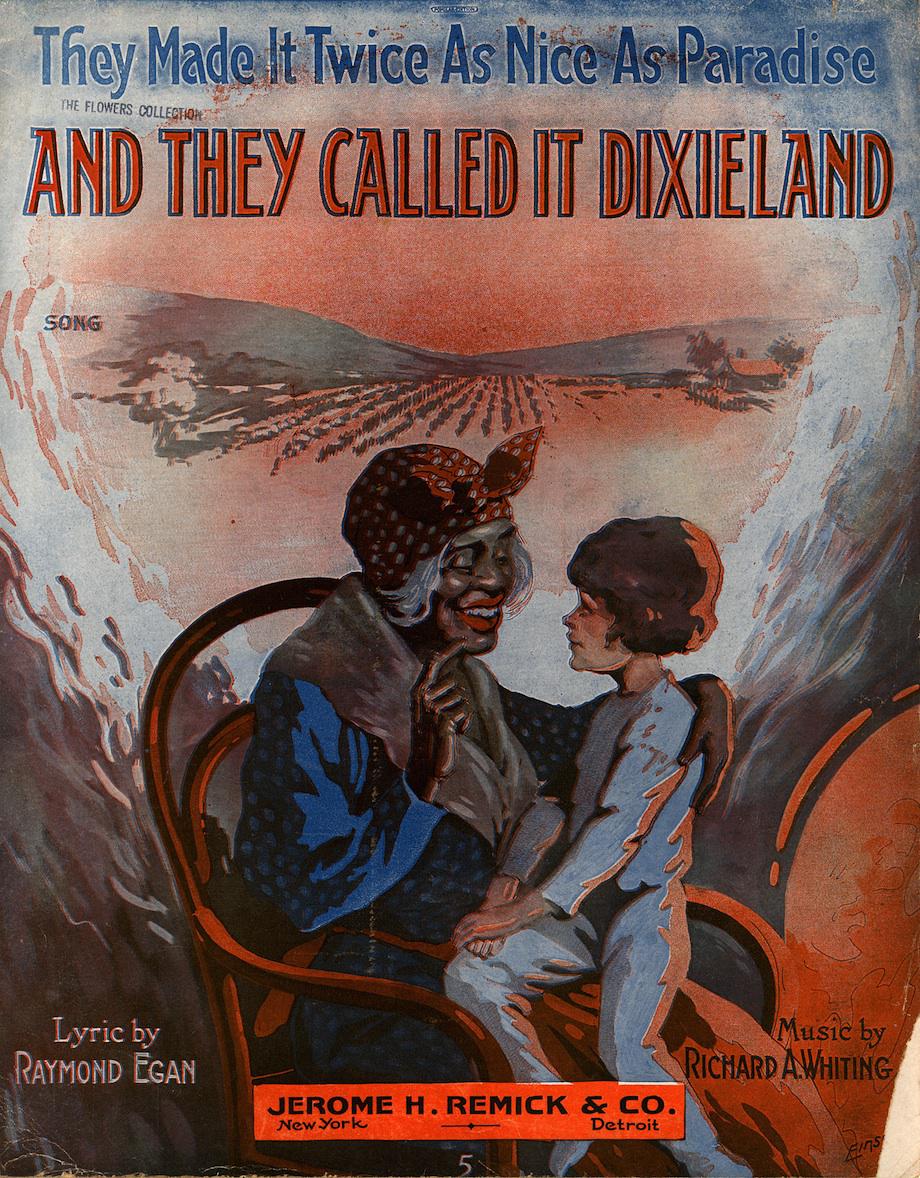

A large subgroup of songs about the South published during this time were written from the point of view of African-American Southerners who loved the South. For example, the cover of “They Made It Twice As Nice As Paradise And They Called It Dixieland” (1910s) depicts a black “mammy” figure telling a white boy about the wonders of Dixie.

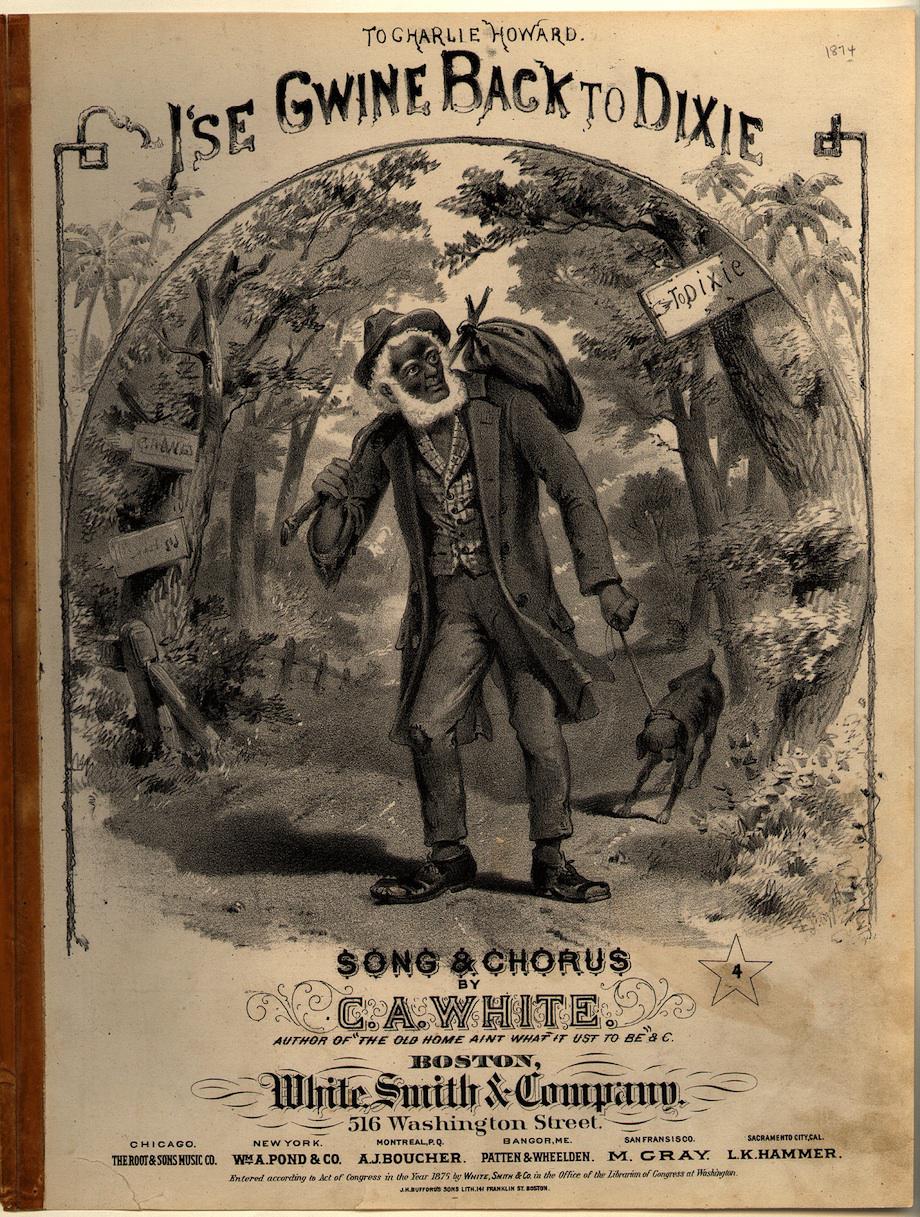

Some of these songs even took the voice of ex-slaves who wished they were back on the plantation. “I’se Gwine Back to Dixie” was one of these. “Sung” by an elderly man who had “hoed in fields of cotton” and sworn to leave the South forever but then decided he couldn’t live away from his home, the song indulges a white fantasy of reconciliation, implying that slavery wasn’t so bad after all.

Published in the 1870s in Boston, this song shows that the dream of racial regression wasn’t simply a Southern one. In fact, many of these songs were written and printed in northern cities.

Historic American Sheet Music - Item A8908. Rubenstein Library, Duke University.

Historic American Sheet Music - Item B0248. Rubenstein Library, Duke University.

Historic American Sheet Music - Item B0742. Rubenstein Library, Duke University.

Correction, April 9, 2013: This post originally misspelled Lynyrd Skynyrd.