The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

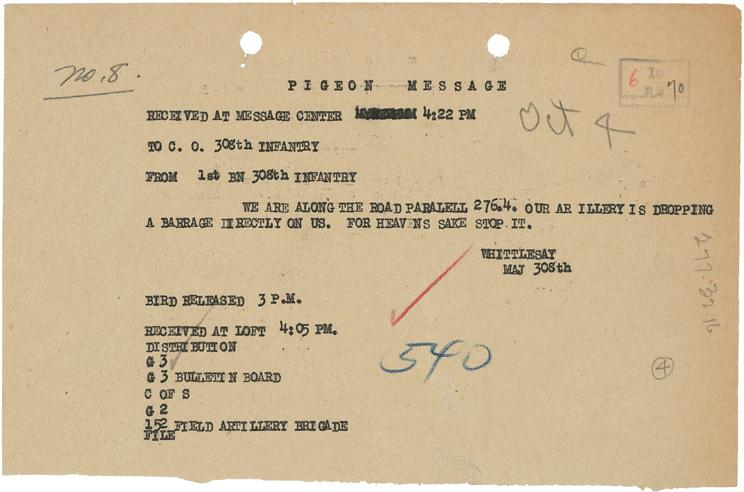

This is a field transcription of a message from Maj. Charles Whittlesey to his commanding officer, delivered by pigeon on Oct. 4, 1918. Whittlesey, commanding nine companies of the U.S. Army’s 77th Infantry Division, took up a position in the Argonne Forest in France on Oct. 2, 1918. His group of 550 soldiers was surrounded by German troops and cut off from supply lines. The dramatic situation, which stretched for four and a half days, drew much attention from war correspondents, and the media nicknamed the group the “Lost Battalion.”

Because WWI predated the invention of reliable two-way wireless communication, the armies relied on runners or carrier pigeons to communicate. The U.S. Army Signal Corps used about 600 birds in France during the war. For the cut-off Lost Battalion, the birds were the only connection to headquarters.

The bird that carried this message was named Cher Ami. He was shot while trying to deliver it—when he arrived, the capsule containing the message was attached to a leg so badly hurt that it later had to be amputated—but managed to return nonetheless.

As this message shows, to add to their other tribulations, the Lost Battalion came under friendly fire. Later, the commander of the 77th, Maj. Gen. Robert Alexander, told the press that it was the French—“in spite of my determined protest”—who directed artillery fire on the ravine, “being convinced that the command had surrendered.”

When the Battalion was finally retrieved, 107 of the original group had been killed in action, while 190 were wounded. Whittlesey was awarded the Medal of Honor.

After the war, Whittlesey and some of his group appeared as themselves in a silent film about their experience. Whittlesey, by all accounts a shy and retiring man, was in constant demand as a speaker.

Whittlesey vanished from a United Fruit Company steamship en route from New York to Havana in 1921. Although his body was never found, it’s presumed he committed suicide by jumping into the sea; he left a will and farewell notes to his family and his law partner. “War preyed on his mind,” the New York Times reported.

Cher Ami died in 1919. He was taxidermied, and the Smithsonian holds his body.