The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

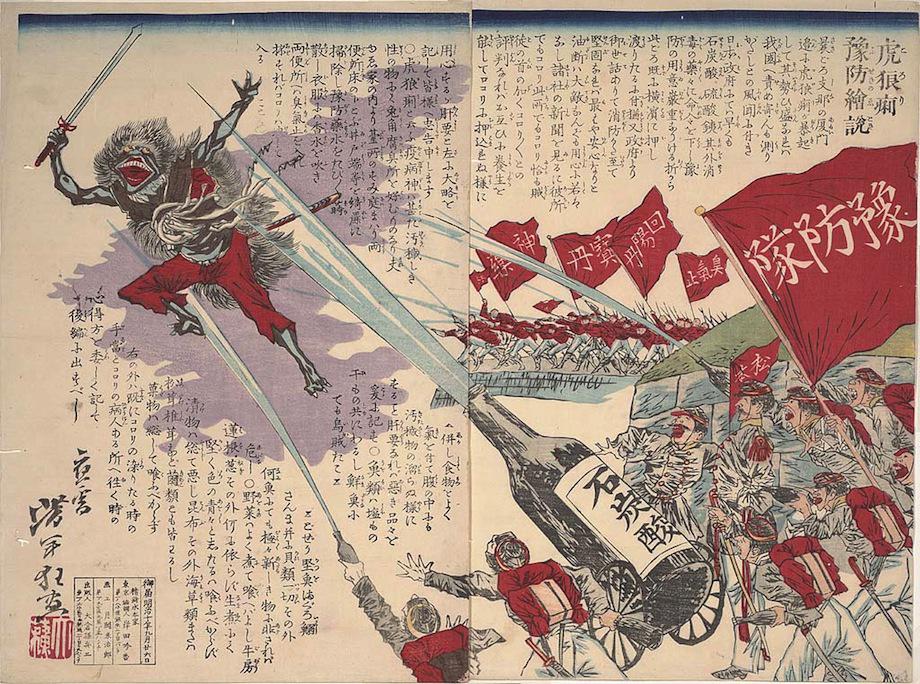

These woodblock prints, produced in Japan in the late 19th century, represent battles with the diseases of cholera and smallpox. As Japan remained largely closed to Western trade until Commodore Matthew Perry forced ports to open in 1854, the woodblocks show how Japanese people’s conception of sickness, health, and medicine changed through early contact with Westerners.

The University of California at San Francisco has a large collection of woodblock prints produced in this period. In an essay on these prints, Laura W. Allen writes that the art would have been produced cheaply and distributed at low cost. Some of these prints may have been handed out as advertisements for medicines, while others were simply meant as topical entertainment and decoration.

The first two images, which show people fighting figures that represent cholera, feature cannons spraying a liquid. This, Allen suggests, would have been carbolic acid, a strong antiseptic then used to combat the spread of the disease, which was basically unknown in Japan before it was opened to trade. In the first print, cholera is represented by a tiger, which the Japanese often associated with the fast-moving, lethal affliction. Here, the tiger leaps at the men wielding the carbolic acid, crushing several people under the weight of its pendulous anatomy.

The third image shows a demon, representing smallpox, menacing two pockmarked sufferers. Allen writes that smallpox outbreaks were documented in Japan as early as 735. For years, people put protective images called hōsō-e up in their houses when the disease threatened. Although many Japanese had stopped using these images by 1890, when this print was produced, the inscription indicates that the artist took his inspiration from an old hōsō-e he saw in somebody’s home. Allen writes,

In other words, [a] “modern” Japanese knew that this sort of talisman was outdated…but might still hedge his bets by employing one of the charms if the need arose.

Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Library and Center for Knowledge Management, University of California, San Francisco.