The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

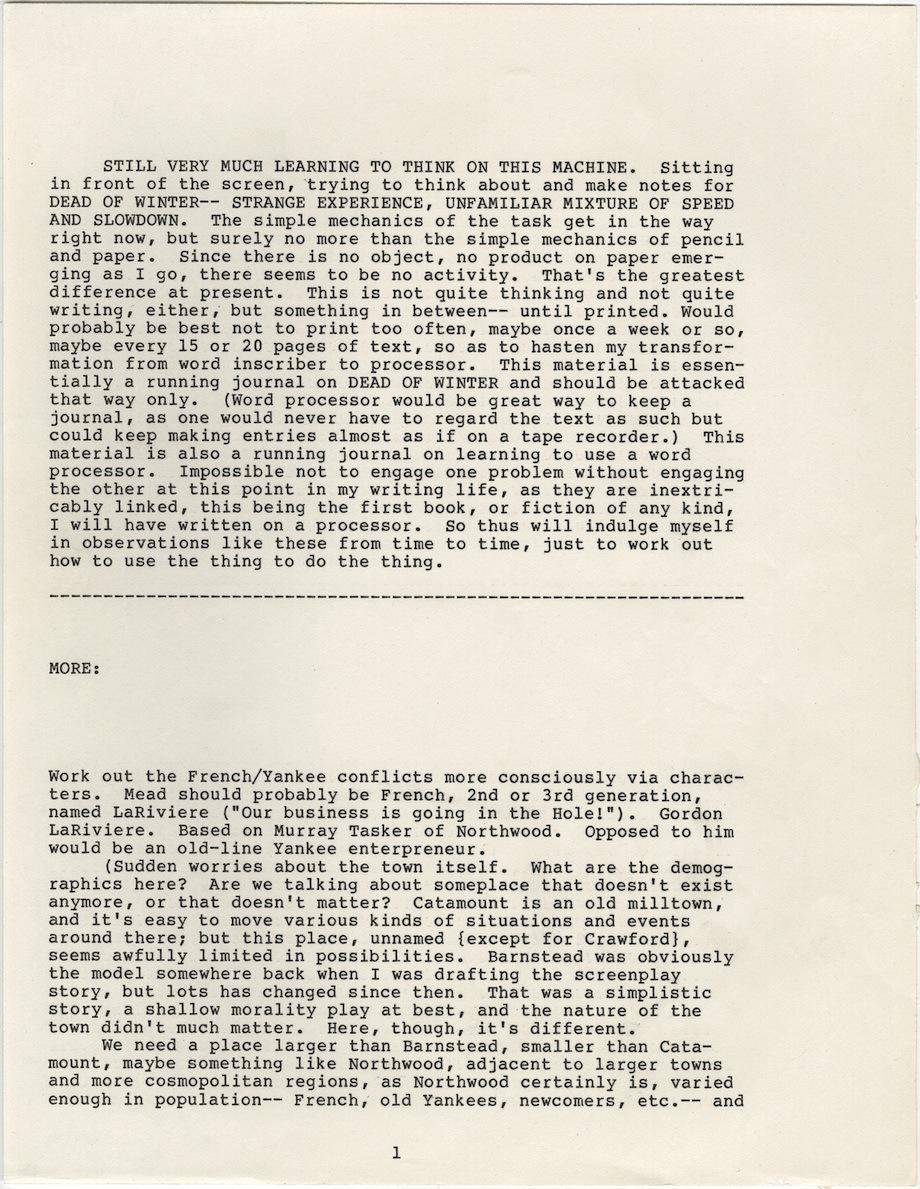

On this sheet of paper, the novelist Russell Banks, who was working on an early version of the book that would become Affliction (1989), made some free-form observations—the beginning of what he called a “running journal”—about his reactions to his new word processor. Writing and learning to word process, he wrote, were “inextricably linked” at that point in his life, so he would “indulge [him]self in observations like these from time to time, just to work out how to use the thing to do the thing.”

Banks was dubious about his relationship with the technology, saying that the “simple mechanics of the task” were problematic. The experience was “an unfamiliar mixture of speed and slowdown.” But his biggest issue with the new way of writing was the immateriality of the process: “Since there is no object, no product on paper emerging as I go, there seems to be no activity.”

While Banks was reserved about the usefulness of the processor for his writing, he thought that it would make a great tool for keeping a running diary: “One would never have to regard the text as such but could keep making entries almost as if on a tape recorder.” The bottom half of the page contains some free-associative brainstorming on the characters and setting of Affliction (then called Dead of Winter) that show how this approach might work.

You can read about the first novel ever written on a word processor—Bomber, by Len Deighton, which was published in 1970—in this recent Slate Book Review piece by Matthew Kirschenbaum.

Thanks to Matthew Kirschenbaum and to Jennifer Tisdale at the Harry Ransom Center.

Russell Banks’ notes about his early experiences writing on a word processor. Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center.