The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

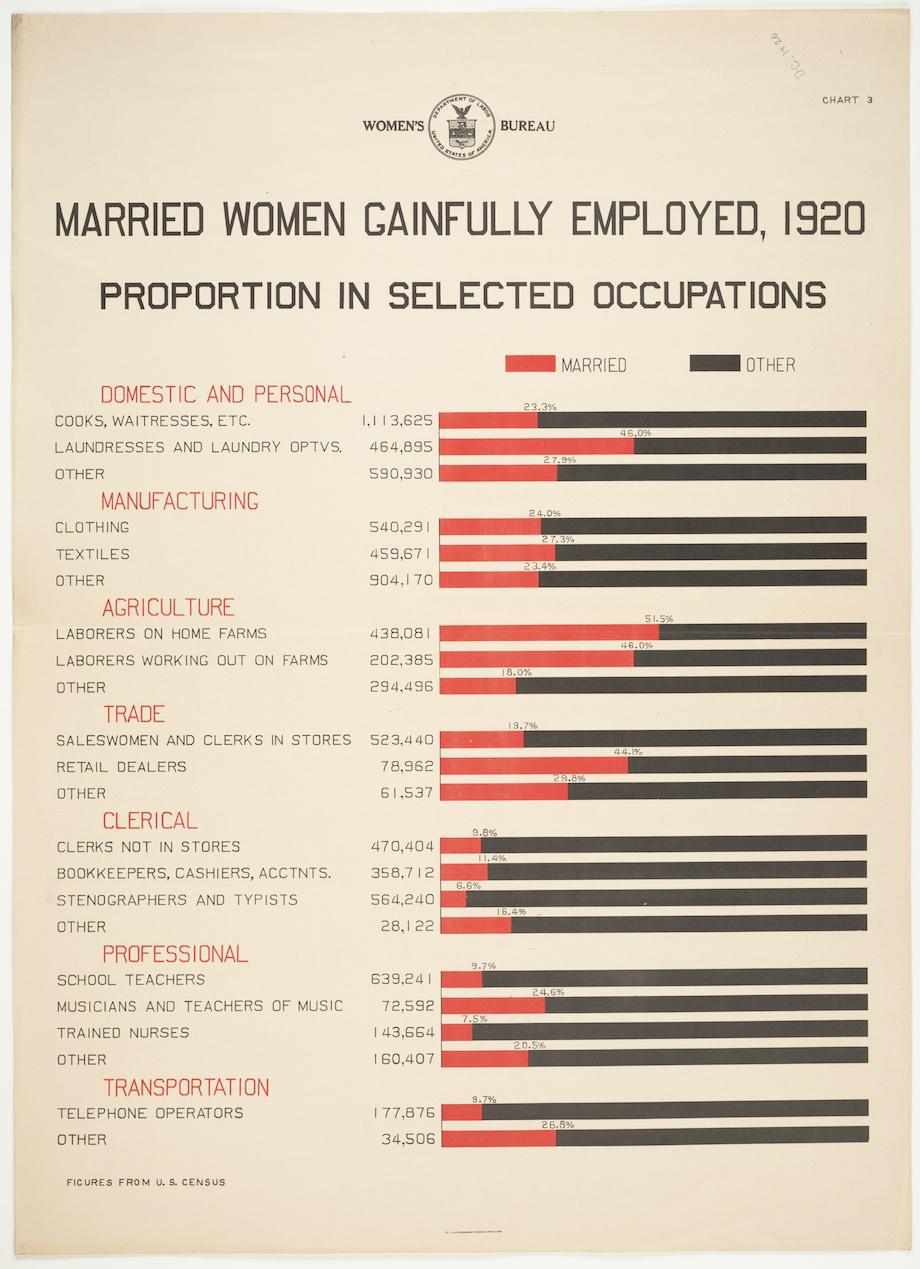

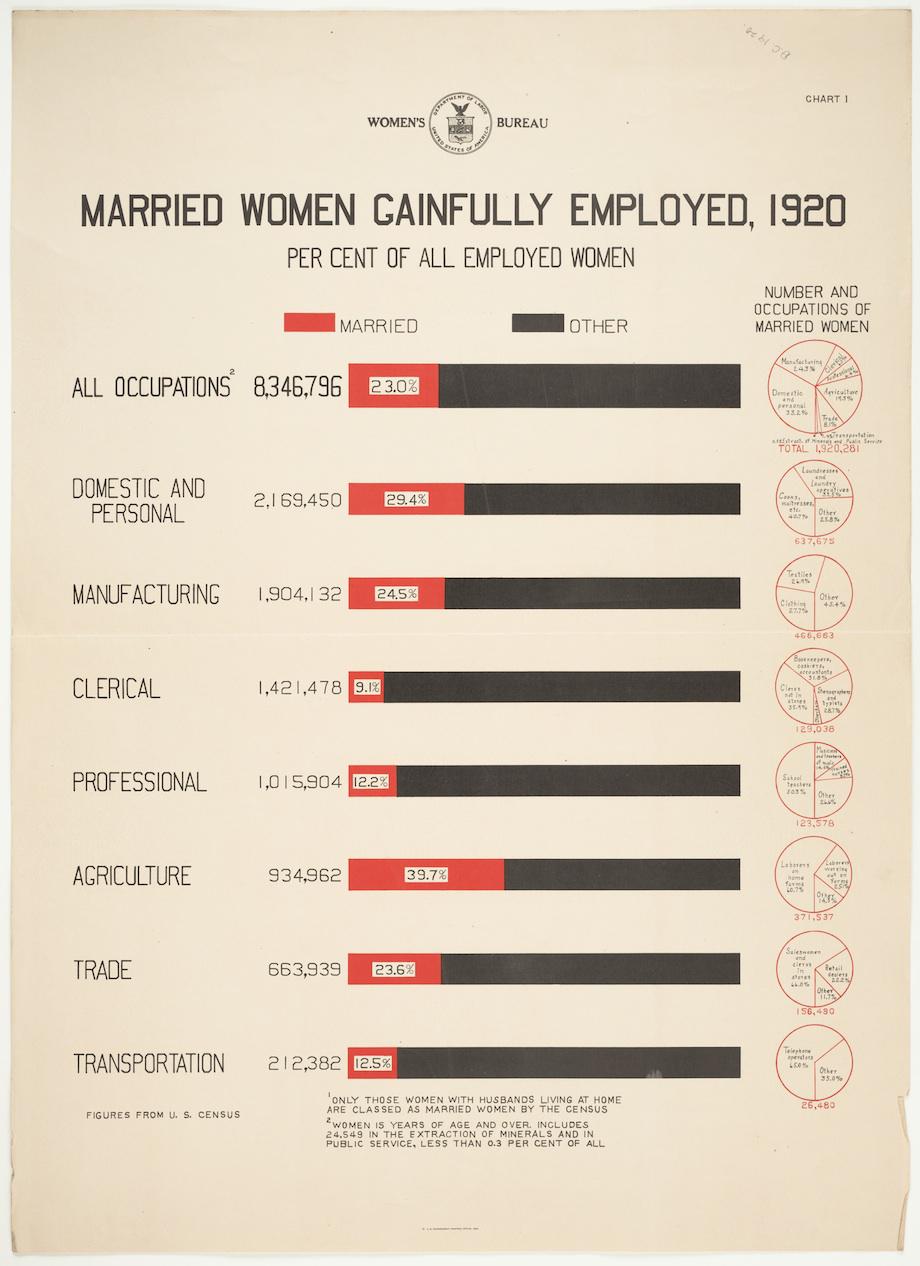

There is a persistent but erroneous belief that before the 1970s American women stayed out of the workforce. Here are two charts that bust that myth. They were published by the Women’s Bureau of the US Department of Labor in 1928, summarizing data from the 1920 Census on the number of women, single and married, in particular professions.

The charts break down the occupations of 8,346,796 women who were “gainfully employed” when the census takers posed their questions in January, 1920. (For context: The total resident population recorded in 1920 was 106,021,537.)

The figures show that women’s work was, on the whole, segregated in familiar sectors: clerks, bookkeepers, stenographers, laundresses, waitresses. “Professional” women were most often schoolteachers. Most of the women working in “transportation” were telephone operators. (In the 1920 Census, there was no separate occupational category for communications workers. Telephone and telegraph workers were classified as part of “Transportation,” because of telegraphy’s early relationship with railroads.)

The Women’s Bureau, created in 1920 to advocate for women workers, was particularly concerned with publicizing the growing proportion of married women who were working. In a 1929 article on this census data for the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Agnes L. Peterson, then the assistant director of the Bureau, pointed out that the share of married women “gainfully employed” had increased from 4-5 percent in 1890 to 9 percent in 1920.

Comparing the average earnings of a factory worker and the cost-of-living in major US cities, Peterson wrote: “For unskilled laborers in general annual earnings are not sufficient to maintain a decent standard of living.” The wages of women workers, then, were essential to the family finances, not simply a garnish to the man’s earnings—a fact that was key for the Bureau’s ongoing crusade to end wage discrimination.